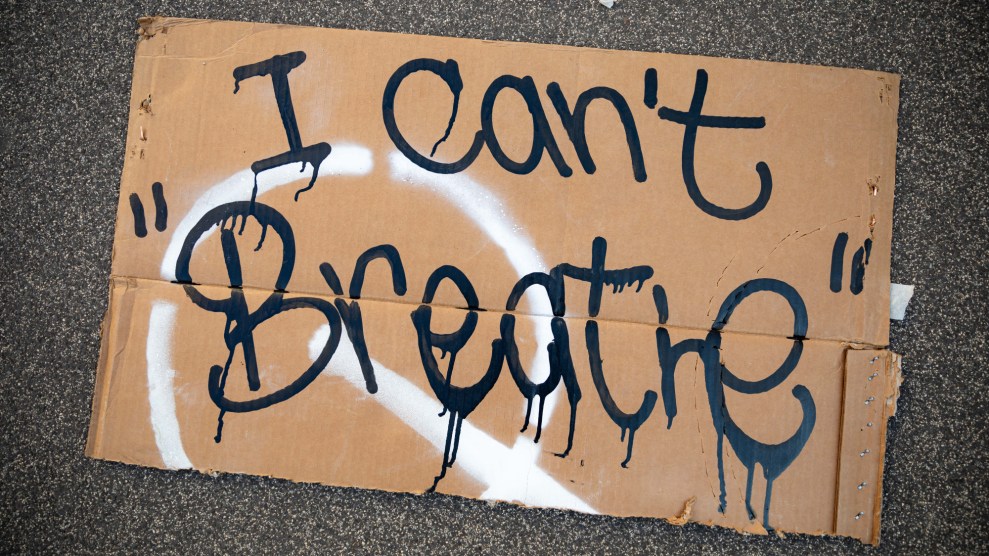

Alessandro Bremec/NurPhoto/ZUMA Press

Nearly a month before George Floyd was asphyxiated at the hands of police, a Black teenager in Michigan named Cornelius Fredericks cried out “I can’t breathe” while two adults who were supposed to be taking care of him pinned him to the floor. Fredericks, a 16-year-old ward of the state, was at a juvenile residential facility in Kalamazoo called Lakeside Academy, and he was being restrained for allegedly throwing a sandwich at a staff member. After about 10 minutes, he lost consciousness and went into cardiac arrest. Twelve minutes later, someone called 911. Fredericks was sent to a hospital and put on life support, where he died about 30 hours later, on May 1.

According to a lawsuit filed last week, Fredericks’ death was just one instance in a long-standing pattern of negligence and abuse at Lakeside Academy. In the six months prior to Fredericks’ death, Lakeside had six separate incidents of employees misusing deescalation techniques, including improperly restraining children. After Fredericks’ death, Lakeside’s board chair said some kids fled the campus; the lawsuit and bystanders allege they were tear-gassed in response.

“It was a torture chamber,” says Geoffrey Fieger, a lawyer suing Lakeside Academy on behalf of Fredericks’ estate. In the days since he filed the suit, he says a number of former and current residents contacted him to share similar stories. “These kids were being brutalized. They sat on [Fredericks] just like they did George Floyd—they suffocated him.”

And this wasn’t the first time Fredericks in particular had been targeted.

In an incident at the beginning of the year, recounted in a 63-page report by Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services, Fredericks was held on the ground by five Lakeside staff for more than 30 minutes, in violation of a facility policy that restraints last for no more than 10 minutes. When the restraint finally ended, video footage showed that Fredericks appeared “unsteady when he stands, and staff escort him by both arms out of camera view.”

Lakeside Academy, which housed about 100 teenagers, was temporarily shut down last month after revelations about Fredericks’ death, and Michigan’s Health and Human Services director announced the state would be disallowing licensed child-care facilities to use restraints like the one used on Fredericks. But facilities like Lakeside abound across the country. Sequel Youth and Family Services, the company that runs Lakeside (and is also a named defendant in the lawsuit), operates at least 55 other facilities from Arizona to Maine.

According to media investigations, watchdog reports and lawsuits, Sequel programs have endangered kids for years.

“We’ve heard in at least eight different states, a history of physical abuse, sexual abuse, abuse of restraints,” said Alyson Clements, director of membership and advocacy at the National Juvenile Justice Network. “Sequel is going into states, buying facilities and running programs that are supposed to be treatment facilities to help young people. But rather than actually helping young people get over these issues, they’re causing grievous harm.”

Advocates are now pushing to have all Sequel facilities in the country shut down. It only takes looking back a few years to see why.

In 2018, Disability Rights Washington demanded that the state stop sending foster youth to the Clarinda Academy, Sequel’s flagship facility in Iowa, after interviews with residents revealed the academy was unnecessarily punitive and lacking in oversight. The group’s report to Washington’s Department of Children, Youth, and Families states:

Clarinda Academy uses physical restraints on a daily basis. The young interviewees described the same process and type of seated and supine restraints being used at Clarinda Academy. Multiple students demonstrated the same moves that staff use to pull their arms behind their back and force the student to sit on the ground where other staff would then assist in holding the student down. Several stated that the staff immediately put them on the ground and rarely if ever use standing or escort restraints. In several students’ words, “they just drop you.” One person reported being grabbed and forced to sit on the ground in a forward folded position so that the student’s head hit the ground, which resulted in the individual’s glasses getting broken. While conducting the interview, DRW observed this young person’s glasses were taped together.

A year earlier, a young woman from Texas sued the Clarinda Academy for negligence and failing to supervise their male staff members. When she was a 17-year-old resident at the Academy, she says, she was raped by a male counselor. He later pleaded guilty to criminal charges of sexual misconduct with a minor, an aggravated misdemeanor. The civil suit was dismissed last year.

In April 2019, after worsening violence at Sequel’s Red Rock Canyon School in Utah, a riot broke out at the facility. Amid the chaos, a male staff member allegedly punched residents in the face and dragged one girl around by her hair; a SWAT team had to intervene. (The staffer was charged with misdemeanor child abuse for the incident, but charges were later dropped.) A Salt Lake Tribune investigation found that between 2017 and 2019, police had been called to Red Rock Canyon School 72 times—often for child abuse complaints—and 10 employees (including the aforementioned male staffer) had been charged with child abuse for choking, pushing, or punching kids in the face. The state of Utah threatened to pull the facility’s licensure and Sequel shut the school down in July 2019.

That same month, an investigation by WBNS, a CBS-affiliate station in Ohio, revealed that Sequel Pomegranate, a Columbus-area youth psychiatric and behavioral treatment facility, had more than 400 calls for police service between 2017 and 2019. In that time, there were 26 instances of staffers accused of “improperly restraining or assaulting teens”; 11 of those staffers had been fired or retrained.

While Sequel doesn’t operate facilities in Oregon, lawmakers in the state are investigating out-of-state programs, including some run by Sequel, that house their foster kids. That was prompted by reports of children with disabilities going unmonitored while out-of-state, as well as a class-action lawsuit filed against the governor of Oregon last year alleging that at least 30 local kids had been sent to Sequel facilities in Illinois, Tennessee, and Utah where, “[i]n the year 2018 alone criminal investigations and charges for sexual abuse [had] been brought against employees.”

In October 2019, Sara Gelser, the Oregon lawmaker who is spearheading the state’s inquiry into the living conditions for out-of-state foster youth, said she first heard of improper and excessive restraints being used at Northern Illinois Academy, a Sequel facility outside Chicago.

“I did a series of public records request, I found small children, 9-10 years old were being subjected to the same type of restraints that you saw with Cornelius, supine restraints where you’re held on the ground, immobilized, facing-up,” Gelser told WWMT, a news station in western Michigan. Since the lawsuit, Oregon has worked to reduce the number of foster youth they send across state lines.

Research shows that youth of color, like Fredericks, are more likely than their white counterparts to end up in facilities like Sequel’s. Black and Brown kids are overrepresented in both the child welfare system and the juvenile justice system. Though no one I talked to knew the racial demographics at Lakeside Academy, Fieger, Fredericks’ family’s lawyer, said all of the residents that reached out to him were Black.

“We know that communities are overpoliced and that schools are overpoliced—particularly schools where Black and Brown young people go everyday,” says Clements of the National Juvenile Justice Network. “And so they’re more likely to end up in the justice system for regular youth behaviors. When you look at different states, you see the deeper you go in the system the more discrepancies exist. A young person moving through the system is more likely to be placed in a residential treatment facility or some other out-of-home placement just due to disparities, implicit bias and our system of overpolicing youth of color.”

As for Lakeside Academy, incident reports to Michigan’s child welfare licensing agency reveal nearly a dozen substantiated claims of neglect and abuse—both physical and verbal—by staff members over the past two years. Residents reported being cussed at, slapped, choked, scratched, and more.

In an email, a Sequel spokesperson said that it is accelerating an organizational restructuring toward “a holistic culture transformation to trauma-informed care.” The three staff members whose actions (or inaction) killed Fredericks have all been criminally charged with involuntary manslaughter and second-degree child abuse; Sequel says it supports the charges and is cooperating with the investigation.

“The tragic loss of Cornelius at Lakeside Academy has only served to strengthen our resolve to reduce, minimize, and eventually eliminate the use of restraints on our campuses,” the spokesperson wrote.

But child welfare advocates are skeptical that reforming such a problematic program will be enough. “There’s no accountability or outcome evaluations for the treatment that these facilities are providing,” says Jason Smith, a policy director at the Michigan Center for Youth Justice. “If you care about public safety, if you care about children’s health, you have to care about these facilities that are supposed to be caring for the most vulnerable people.”

Just two weeks before Fredericks’ death, the company announced it would be expanding into Texas. According to the press release, the move will include several new nonresidential therapy programs for people on the autism spectrum or with speech disorders, intellectual delay, and neurological or attention deficit disorders.

“Sequel will now be providing care to more than 10,000 patients annually,” they wrote.

Do you have a Sequel story? Email me at lthompson@motherjones.com.