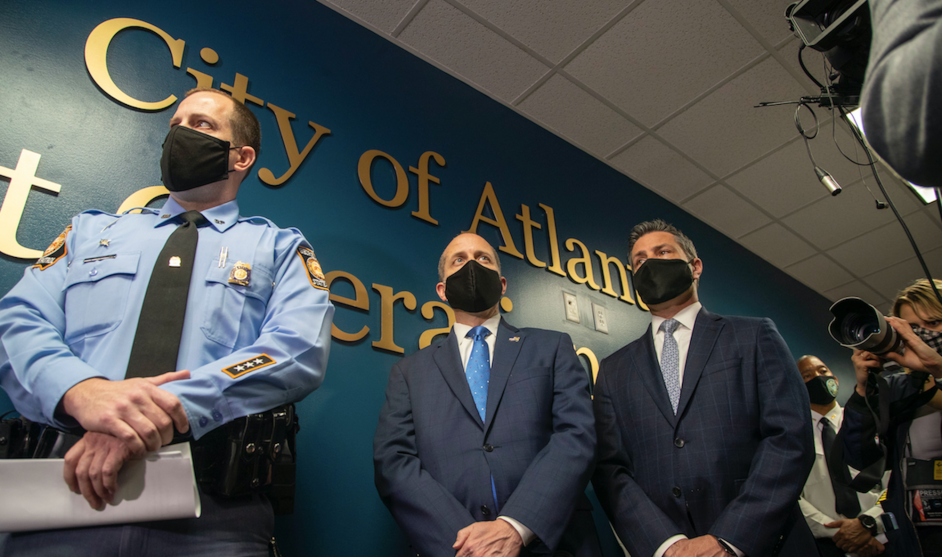

Elijah Nouvelage/Getty

The morning after a gunman attacked three massage parlors in the Atlanta area, killing eight people, including six women of Asian descent, JM Wong and a few other members of the Massage Parlor Outreach Project visited nearly a dozen spas in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District. Since 2018, Wong and her team have been visiting massage parlors around the neighborhood to build community and find out what the employees need to have safer, healthier workplaces. On Wednesday, as news about the murders in Atlanta spread, the workers—mostly women—were feeling “anxious, fearful, helpless,” Wong says. “We heard so many people say, ‘I’m scared, but what can I do? The shop has to stay open.'”

Wong handed out candy and tampons, staples of her group’s outreach, and asked the workers what they needed to stay safe. Several asked for pepper spray. Others wanted more community members present in and around the parlors to keep an eye on things. No one, she says, asked for more police.

Yet that’s exactly how public officials have responded to the deaths of Soon C. Park, Hyun J. Grant, Suncha Kim, Yong Yue, Daoyou Feng, Xiaojie Tan, Delaina Ashley Yaun, and Paul Andre Michels. Police arrested the alleged killer, a 21-year-old white man, on Tuesday evening, and he was later charged with eight counts of murder. In the days since, the mayors of New York, San Francisco, and Chicago have announced that they would step up law enforcement presence in Asian American neighborhoods. Police departments in the Atlanta area, meanwhile, say they have already deployed patrols “in and around Asian businesses, particularly spas”—despite local law enforcement officials’ ludicrous claims that racism did not play a role in the shootings.

The moves toward more policing are motivated by public pressure for officials to respond to the rise in anti-Asian violence widely attributed to the pandemic and former President Donald Trump’s anti-Chinese rhetoric. While hate crimes are notoriously underreported, and data on their prevalence is unreliable, a recent study by Stop AAPI Hate tallied reports of nearly 3,800 hate incidents against Asian Americans since last March. “What happened yesterday felt so very personal for many of us, because we’ve all been in that situation where we have been targeted because of our race and gender,” says Sung Yeon Choimorrow, executive director of the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum. In Stop AAPI Hate’s tally of anti-Asian hate incidents, 68 percent of reports were made by women.

But community organizers and advocates for massage workers, women of Asian and Pacific Islander descent, and Asian migrant sex workers say that policing is not the answer—and often is a source of stigmatization and violence. Instead, they want public officials to recognize the intersecting roles of racism and misogyny in the Atlanta murders. And they are calling for structural changes—like easier access to social services for people who do not speak English, health care access for recent immigrants, and respect for the labor rights of massage parlor workers—that they say would make members of their communities less vulnerable.

The victims of the Atlanta murders “are regular, low-wage women showing up for work, and they never came home,” says Leng Leng Chancey, the Georgia-based executive director of 9to5, which fights for economic security for working women. “We can’t forget that.” Instead of more policing, she would like to see transformative justice programs that address the root causes of violence and hate as well as greater investment in social services that will benefit AAPI workers.

“Law enforcement is a tool to protect white supremacy. It’s not here to protect us,” says Choimorrow. “That’s what I keep telling people who want to call on increased law enforcement as the solution to what happened. I would not feel any safer having more cops running around my neighborhood, because that’s a Band-Aid to a much more deeply rooted problem.” “So many people are really quick, to answer back to anti-Asian violence with saying we need more policing, or we need punishment. And we don’t think that’s true,” says Yves Nguyen, an organizer for Red Canary Song, a collective of Asian sex workers and allies. “The more police that…show up in that area of Georgia, are only going to lead to more people being harmed.”

On Wednesday, the Cherokee Sheriff’s Office put out a statement saying that the alleged shooter told officers that his crime was “not racially motivated”; the sheriff also told reporters that the suspect said he struggled with “sexual addiction” and had called the massage parlors “a temptation he wanted to eliminate.” Sexualizing Asian women is part and parcel of anti-Asian racism, says Choimorrow, who was born in Korea. “That’s one of the stereotypes about Asian American women—that we’re temptresses, that we’re hyper-sexual, irresistible, whatever,” she says. “Even his excuse that this isn’t a racialized [incident], is playing right into the racialized stereotype about Asian American women.”

On top of sexualized racism, there are particular risks for massage parlor workers, whose industry is associated with sex work regardless of whether or not they participate in it. “There are massage parlors in every city, every suburb in the US, and there’s only one narrative to describe people’s experiences, which is that they’re trafficked,” explains Wong, in Seattle. Yet most workers tell her they are there by choice, whether they sell sex or not. “What we have heard from women we talked to, people have been assumed to sell sex, even when that’s not what they do,” Wong says, “and clients take liberties with them.”

It’s not clear whether the women murdered in Atlanta did sex work as part of their employment at the massage parlors. It’s also not clear whether the alleged shooter was a client of the businesses where the shooting occurred. Yet on Thursday, more than 200 sex worker, racial justice, and progressive advocacy groups cosigned a statement by Red Canary Song drawing attention to link between the “specific racialized gendered violence” in Atlanta and anti-sex work stigma: “Whether or not they were actually sex workers or self-identified under that label, we know that as massage workers, they were subjected to sexualized violence stemming from the hatred of sex workers, Asian women, working class people, and immigrants.”

Nguyen, of Red Canary Song, says massage workers have nowhere to go when they are victims of violence, in part because of the perception that they do illegal sex work. “Here in New York, the NYPD raids massage businesses and arrests people, regardless of whether or not those people engage in sex work,” they say. “It doesn’t matter if they were doing sex work, they’re going to be criminalized all the same—for being Asian women, for being migrants, for some of them being undocumented, and for doing labor that’s often connected to sex work.” Red Canary Song formed in 2018, after Yang Song, a 38-year-old massage parlor worker, fell to her death from a fourth-floor apartment while police were attempting to arrest her for selling sex.

Many massage parlor workers associate any kind of police interaction with the possibility that they will be reported to Immigration and Customs Enforcement and deported. Chancey, of 9to5, emphasizes that this fear is common across immigrant communities. “So many of us already are afraid, our families are afraid to speak to anyone, because we have local police and sheriffs departments that work directly with ICE,” Chancey says.

On Thursday night, Red Canary Song held an online vigil for the people murdered in Atlanta. Speaking through an interpreter, a massage worker named Lisa talked about how vulnerable she and other workers can be to robbery, sexual harassment, and violence. “Due to the racism and the lack of support from the government, we need to feed ourselves by our own hands,” she said. “The police are not able to help us, even if we call the police after the incident. With the ongoing harassment from the police and law enforcement officers, we can only rely on ourselves and our sisters to keep ourselves safe.”

Wong says police raids and a dwindling clientele during the pandemic have contributed to the closure of more than half of the massage parlors in the Seattle district where she visits workers. “What we hear from most of the people we talk to is people are choosing to do massage parlor work—which isn’t all sex work—and these raids actually destroy people’s livelihood. Oftentimes, people are jailed.” Some of the spa workers who remain in the district have told her they now work alone because they can’t afford to hire staff.

During Wong’s rounds on Wednesday, one woman told her she had been working alone when a man entered the shop and began choking and assaulting her. “She had to fight him off,” Wong says. “But she never called the cops. And she stays open. We asked her, ‘Isn’t it scary? What else can be done?’ She’s like, ‘I have no choice, I have to stay open. Even if it’s one or two customers a day, we need that.'”