The transporters from the Baltimore Department of Social Services arrived at Stevie and Eric’s doorstep late one night last March, after the couple’s two kids had gone to bed. Their son, just a few weeks old, slept as a DSS employee carried him to the car. But their 2-year-old daughter, awakened and confused at the sight of masked strangers in the living room, began to wail. She looked toward Stevie, who was also in tears. A year later, Stevie replays the moment over and over. “All I can still picture is them trying to carry her out the door and her little hands holding on the door frame, crying ‘Mommy,’ trying to hold on,” Stevie recalls. “And them pulling her away.”

It would be four months until Stevie and Eric saw their children again.

The family’s experience with Maryland’s Child Protective Services started shortly after the birth of their son in February 2020, when tests found cocaine in his system. The baby and his sister were placed in the care of Eric’s mother for a few weeks, returning home after a magistrate ruled that they were safe with Stevie and Eric, a stay-at-home mom and construction worker, respectively, with no prior CPS history. (The parents in this story are using only their first names to protect their privacy.) The couple’s court-ordered drug tests were clean in the weeks to come. But CPS rejected the decision to return the kids to their parents, and in late March, another judge ruled in the agency’s favor. Hours after the ruling, the DSS transporters arrived to take the children back to their grandmother’s house.

Like her namesake, Fleetwood Mac’s Stevie Nicks, Stevie has big brown eyes and a quiet, unwavering voice. The 27-year-old readily admits to a history of drug use that evolved from Percocet after an injury in high school to heroin in her early 20s. In recent years, she quit using illicit opioids but continued to use cocaine. Eric had gone through cycles of drug use too, most recently popping Xanax in the evenings to destress after putting his daughter to sleep. They told themselves they were being good parents even as they used. Their daughter had no shortage of food to eat or toys to play with. She loved “helping” her parents make dinner, stirring the pasta, arranging the cans of soup.

But looking back on it now, Stevie understands why CPS got involved. She cringes at the memories of stepping outside to use during nap times and selling family belongings for drugs. “I know from the outside, it seems like, ‘She got her kids taken. She was still using drugs. She must be a piece-of-shit mom and not care,’” she said when we first spoke last August. “That can’t be further from the truth. My kids are my everything.”

Under normal circumstances, this would have been a straightforward child welfare case: Stevie and Eric would have attended a hearing scheduled for the first day of April 2020, when a judge would lay out the requirements they would need to fulfill to reunite with their children, such as addiction treatment and parenting classes. They would have seen their children for regular visits, first during supervised appointments, and, with time, on their own. Assuming the couple stayed off drugs, the kids would likely have come home by last summer. “We would have worked through getting her the right treatment and we would have been fine,” says David Wanger, a Baltimore public defender who represented Stevie. “We would have had the trial. It would have been resolved. She would have had regular weekly visitations.”

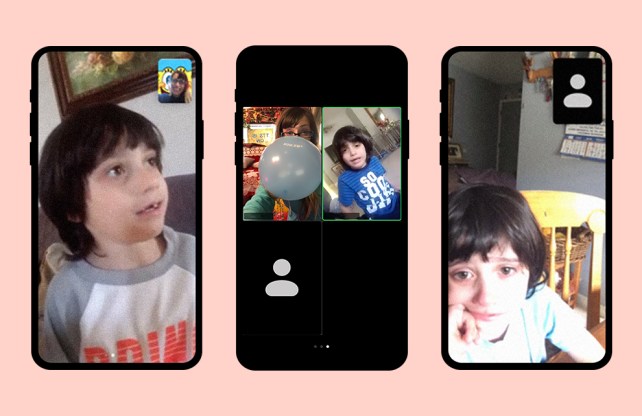

But shortly after the children’s removal, the pandemic shut down Baltimore, including the courts hearing child welfare cases. CPS transitioned to virtual visits when the pandemic began, and suddenly Stevie and Eric could only see their children in fleeting Zoom chats. Eric’s mother, with whom the couple had never gotten along, would point the camera at their infant son before their daughter would take over, swinging the phone around the room. Sometimes, their daughter put down the phone as she went off to play with her toys, coming back and wondering where her parents had gone. “I think in her mind, she knew we were there on the phone, and she wanted to just have us there playing with her,” Stevie says. “Nobody could explain why she could see Mommy and Daddy but she can’t see Mommy and Daddy.”

As the pandemic has slowed the child welfare system, thousands of fractured families like Stevie and Eric’s have been in limbo. Family court shutdowns created case backlogs across the country. As in-person visits became virtual, parents went weeks or months without seeing their children. Therapy, addiction treatment, and classes parents needed to complete to reunite with their children became even harder to access.

In a typical year, a little more than half of the children in foster care return to the permanent care of their biological parents. Experts agree that this outcome, called reunification, is by far the best option if parents prove to be safe caregivers. But in 2020, reunifications plummeted, according to public records from more than a dozen municipalities examined by Mother Jones. In effect, many families that normally would have been reunited remain separated.

Some municipalities saw slight reductions in their foster care populations in 2020, likely due to children having less contact with teachers and other adults who are legally required to report suspected child abuse or neglect. But reunifications dropped at far steeper rates—by 20 percent or more in seven out of the 10 most populous cities. In Los Angeles, home of the nation’s largest municipal child welfare system, about 1,000 fewer children were reunified with their parents in the year ending July 2020 compared with the previous year. In Baltimore, reunifications fell by more than a third, from 299 in 2019 to 188 in 2020. (“We are genuinely concerned about the impact of the coronavirus on the children and families we serve,” said a Baltimore Department of Social Services spokesperson. He added that, at the start of the pandemic, the agency surveyed hundreds of foster parents to “check their health and wellbeing.”)

The long-term psychological toll of delayed reunifications is incalculable, particularly for the roughly 130,000 infants and toddlers in the foster system. “Babies who are not smelling their mom and hearing their mom’s voice the majority of every single day are going to suffer consequences, and toddlers don’t understand what’s going on and why it’s happening,” says Dennis Smeal, executive director of Los Angeles Dependency Lawyers, which represents parents in child welfare cases. “We don’t know what those consequences are going to be. Therapists 30 and 40 years from now will be telling us that story.”

While gruesome narratives of child abuse dominate the media coverage of child welfare cases, the vast majority of cases are triggered by “neglect,” a catch-all category of offenses often caused by privation or addiction. “Most of the families that we deal with find themselves in a situation that’s been brought on by years of living in poverty and not having the basic things that they need,” says Jerry Milner, who led the US Children’s Bureau, the federal agency overseeing child welfare, until this January. The overwhelming majority of families ensnared in the child welfare system are poor, and a disproportionate number are families of color. Black children are twice as likely as white children to wind up in foster care. “Child welfare exists in a space where poverty and public health and civil rights collide,” says David Kelly, another top official at the Children’s Bureau. “If that wasn’t clear prior to the pandemic, it really should be glaring now.”

Alarmingly, the pandemic could result in the permanent separation of families that would otherwise be reunited: Federal guidelines dictate that parental rights are terminated if children remain in foster care for 15 of the previous 22 months. Once those rights are terminated, children are effectively freed up for adoption. Milner and Kelly have been trying to sound the alarm since last spring, when they warned that without policy changes, the pandemic could lead to “the redistribution of other people’s children.”

When I first spoke with Stevie last summer, her grief seemed to pulse through the phone line. The hearing that was supposed to happen in April had been pushed back six months. She and Eric had seen their kids in person just once since March, spending a couple of surreal hours at a recreation center in late July. As the family had snacks and played games, a monitor watched through a two-way mirror. Stevie and Eric’s daughter seemed excited to see her parents, but was confused about who was in charge; she’d developed a habit of referring to all adult women as “mom” and men as “dad.” She had zoomed through milestone after milestone in their absence: She was beginning to talk and had transitioned from diapers to pull-ups. Their son, who they had last seen when he was just a few weeks old, was laughing, eating baby food, sitting up, and rolling over. “Those are milestones that you can’t get back,” Stevie said. She understood why her children were taken away, but keeping them away for so long, with no end in sight, was another matter altogether. “It’s fine to punish me, but not my children,” she concluded. “They didn’t do anything wrong.”

When the pandemic brought in-person visits between children and their parents to the world of Zoom and FaceTime, the limitations forced parents to get creative. After his 12 hours of weekly in-person visiting time was reduced to an hour over video, Michael, a father in Moses Lake, Washington, took to staging onscreen sword fights with his young son. In California’s Monterey County, a mom named Tracy dressed like a clown, blew balloons, and painted pictures to try to keep her 4-year-old son entertained over Zoom. “He’d be like, ‘Mommy, how come I only see you on the phone?'” Tracy remembers.

“It’s extremely hard because he doesn’t understand why he’s not able to see you in person and becomes so frustrated he just wants to hide 😞” a county caseworker texted Tracy. “I feel so bad because he will continue asking when is the ‘red car’ coming to pick up and take him to see you 😭”

Tracy and her son during virtual family visits

The Children’s Bureau attempted to provide guidance to parents stuck with digital visits. “Since you are not able to touch your child to show physical affection, you may need to emphasize other types of communication, such as facial expressions, smiling, and laughing,” read a factsheet the agency published last summer. “Additionally, you can describe or act out the physical touch (e.g., saying ‘mommy is hugging you right now’ while hugging your arms around herself).”

Over the course of a child welfare case, family visits progress from meetings overseen by a CPS-approved monitor to unsupervised overnights and weekends. The visits build on one another, each one a potential opportunity for parents to show caseworkers that they are ready for more time with their children. Judges consider the strength of the family bond, as demonstrated in visits, when deciding if families should reunify. But virtual visits don’t allow the kind of bonding that comes with in-person activities, snacks, and hugs.

Parents and children who saw each other for visits—sometimes as often as every day—were “abruptly cut off, in many places, to zero contact—to absolutely no in-person contact for a child who’s already isolated from their community and their family,” says Leslie Heimov, executive director of the Children’s Law Center of California. “The biggest irony is you can have a foster parent who decides it’s okay to go see her own sister or her next-door neighbor or her best friend. But it’s not okay for the foster child living in that home to see their sister or their mother.”

Even under normal circumstances, the path to reunification can seem capricious, varying dramatically depending on the locale: Regional rules, norms, judges, and caseworkers determine when families are separated and reunified, how easy it is for parents to access required social services, and how often separated children and parents are able to visit. Children in Los Angeles and Phoenix, for example, are between five and seven times more likely to be removed from their homes as children in Houston. New Jersey is piloting a demonstration project aimed at eliminating foster care altogether while, across the state border, Philadelphia has the highest foster care rate of any city in the nation.

The pandemic exacerbated regional disparities, causing reunifications to plummet in some places and stay relatively steady in others. Its effect was particularly pronounced in Los Angeles County, which has about 21,000 children in foster care at any given time. For three months after the pandemic began, the child welfare courts in the county only heard “emergency matters,” explained a Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) administrator in an email. Existing cases were stalled, but new cases kept opening: More than 2,700 children streamed into the system during the first four months of the pandemic. In a presentation last summer, DCFS director Bobby Cagle admitted that nearly 2,200 cases had gone more than three months without a dispositional hearing, when a judge decides where children should live, how often they will see their parents, and what steps parents need to take to complete their cases.

Bree, a mother who lives on the county’s outskirts, is among the thousands of parents with open cases. Her four children, all under age 10, were sent to four separate homes in December 2019. Bree’s case plan recommended she see her kids for a minimum of nine hours a week on the path to reunification, but since the start of the pandemic, she has seen her older children together just eight times. For the rare in-person visits—in a park because of the pandemic—Bree brings paints, slime kits, and contraptions for them to play laser tag. She arrives laden with pizza, cheese sticks, and chicken wings. Bree remembers the dates of these visits by heart. “The happiest moments are the ones that are forever imprinted in my brain,” she says.

But she gets quiet at the mention of her youngest son, who is now 4 years old. She has seen him just twice over the past year. Each time Bree tries to schedule a visit with him, she says, the foster mom wants to reschedule. “We haven’t seen him in months,” says Bree’s mother-in-law. “We don’t even know what he looks like. We don’t even know if he is alive.”

Even in the absence of a pandemic, some families don’t get nearly as many visits as their case plans stipulate, says Smeal, head of the Los Angeles Dependency Lawyers. The logistics of every visit—scheduling, transportation, assigning a monitor—are enormous in a sprawling county with an overburdened foster system. “You can’t help but think about the damage that is being done to the relationship between these children and their parents,” adds Smeal. “You just want to beg DCFS, Take fewer children.”

A DCFS spokesperson acknowledged that the pandemic had made coordinating visits more challenging, but the department “remains committed to reunifying children with their parents, when safe to do so.” She couldn’t speak to Bree’s case, but said, “When a parent or child has concerns about their visitations they are able to contact their attorneys to have their concerns addressed.”

Here, too, the pandemic has put more pressure on an already overwhelmed system as open cases pile up. Court-appointed lawyers representing Los Angeles parents managed caseloads of about 170 clients prior to the pandemic; now, a typical lawyer represents 250 parents, Smeal says. The court-appointed lawyers who represent children are similarly inundated, with as many as 215 cases per lawyer, says Heimov.

Bree was among the many parents I spoke with who didn’t know what they needed to do to reunite with their children. Her demographic is grossly overrepresented in Los Angeles’ child welfare system. She is Black in a county where, in 2020, three quarters of children removed from their homes were Latino or Black, and where child welfare cases involve Black children at a rate five times higher than white children. She doesn’t make nearly enough money to pay for a private lawyer. For months, she frantically called law offices in the greater Los Angeles area in hopes of finding an attorney to represent her pro bono. “We almost feel powerless,” Bree said. “If you don’t have the money for lawyers up front, it’s almost next to impossible.” She had taken to scouring Facebook groups for legal advice.

Although local child welfare rules vary widely, all systems are governed by the 1997 Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA), a Clinton-era tough-on-crime law stipulating that states must initiate the termination of parental rights if a child has been in foster care 15 of the past 22 months. The legislation provides financial incentives for states to increase their adoption rates. In theory, this prevents kids from lingering in foster care for years. In practice, it has led to soaring adoption rates, “perpetuating disparity, trauma, and unnecessary parent child separation,” says the Children’s Bureau’s Kelly. In recent years, reformers have called for a shift of resources from foster care to support services like housing, food, medical care, and day care. “Why not try to prevent as many of these vulnerabilities as we can, rather than waiting for them to occur?” Kelly says.

Technically, when a state fails to provide programs necessary for reunification, families are exempt from ASFA’s 22-month timeline. The Children’s Bureau has urged child welfare systems to be flexible due to the pandemic and ensure that parents are given enough time and support to reunite. But reunification decisions are made by local courts on a case-by-case basis, and the Children’s Bureau is limited to suggesting policies rather than changing them. While terminations and adoptions decreased in many municipalities last year due to the court slowdowns, Milner and Kelly are concerned that the ASFA clock has kept ticking in some places, which could result in a wave of parents losing their parental rights as the courts pick back up.

Last August, Rep. Gwen Moore (D-Wis.) introduced a bill that would suspend the timeline looming over cases. “It’s hard enough, once you’ve taken someone’s child, for them to comply with all the requirements—get a job, get a house,” Moore says. “It’s hard enough to do it under ordinary circumstances. And it’s impossible, we think, within the COVID climate.” Moore knows from personal experience: A half century ago, when she was a first-year student at Marquette University, her daughter was removed from her care for a time. “I saw it as a really zealous effort to deny me an educational opportunity, and deny me an egress out of poverty,” she says. “To break my family up for absolutely no reason.” Moore’s recent bill didn’t go anywhere in a congressional session flooded with pandemic-related legislation. She plans to reintroduce it this year.

Many parents I spoke with for this story had the same two fears: that they would lose custody of their children and that their children were being traumatized by prolonged separation. The first was still a hypothetical, but the second was almost certainly happening.

Even when removal is necessary for a child’s safety, the psychological toll of family separation lingers. Children lose not just their parents but the routines of home, both large and small: the stuffed animals, the familiar smells, the bedtime rituals. Sometimes, they are separated from their siblings or they have to enroll in new schools. Even the most loving foster parents “can’t address the child’s need for all the things and people that they have lost,” says Marty Beyer, a psychologist who advises child welfare systems across the country.

Children often regress developmentally after they are removed from their homes. Potty-trained children, like Tracy’s son, begin wetting themselves. Older children, like Bree’s daughter, backslide at school. Kids of all ages act out in ways that may be mystifying to foster parents and biological parents alike. “When I got my kids back, I didn’t get back my kids,” says Cynthia Becker, a Riverside, California, mother who hosts a Facebook group in which she interviews parents about their CPS cases. Becker’s children, now 8 and 10, returned to her care in 2019 with severe separation anxiety and night terrors. “When we have a knock on the door, all three of us freak out,” she says. “You’re just waiting for the next social worker or something to come to the door.”

Christine Beyer, who leads New Jersey’s Department of Children and Families (no relation to Marty), likens family separation to a broken bone. “Even with reunification, we still have that break in the family,” she says. “It’s still never as strong as it was initially.”

The pandemic has made it harder for those breaks to heal. The usual questions that kids ask about when they’ll go home are more difficult to answer, making separation “even more confusing and less comforting,” says Marty Beyer. Although in-person visits have picked up in recent months, there’s no getting around the fact that infants and toddlers separated from their parents at the start of the pandemic missed months of critical attachment that research has found key to long-term mental health and development. “We can’t fix that,” says Heimov. “We can try to remediate the damage, but we can’t take it away.” As the pandemic fuels food insecurity, housing instability, and loss of income, some parents find it nearly impossible to complete the court-mandated steps to close their cases. In recent months, Heimov has watched parents cave under the pressure of child welfare cases. “If you take a person who’s already fragile, and then add more to their plate, with fewer services available, it’s not surprising that some families that were doing really well might not be doing so well now,” she says.

For Stevie, in Baltimore, the pressure became too much over the summer. She was spiraling into anxiety and depression, not knowing when she would see her kids again. She wondered endlessly about how they were doing. Were they getting enough food? Had they had a bath? How were they sleeping? “I would think about the kids and they’re not here, and then I’d think about my mistakes,” she remembers. “Not being able to see them, not being able to talk to them—it was a kick in the face. It’s like I lost sight of what I was fighting for.” She escaped the same way she had for years: She relapsed.

It’s easy to imagine Stevie and Eric’s case ending in a termination, as so many other child welfare cases do. Bree, in Los Angeles County, recently learned that DCFS will recommend terminating reunification services at an upcoming hearing, which could lead to the adoption of her children. Her caseworker allegedly suggested she hadn’t completed the classes and therapy stipulated in her case plan; Bree maintains that she has. (“Mere attendance in a program is not sufficient,” wrote a DCFS spokesperson, speaking about cases generally rather than Bree’s specific situation. She added that the department looks for “progress towards alleviating those behaviors that placed the children at risk of harm at the beginning of the case.”)

Meanwhile, in Monterey County, Tracy also went into a tailspin after learning that the county was ending reunification services. Earlier this year, a social worker emailed Tracy with the updated schedule for decreased Zoom visits with her 4-year-old as her case nears termination. This month, they’re down to one hour per month. “I mostly go between two modes right now,” she wrote in a recent text. “Hopeless endless kill me now doom or hyper detective” going on “appellant/federal law bingers.”

Improbably, Stevie and Eric’s case ended differently. Stevie’s relapse lasted two months. In August, she stopped using—a development she attributes in part to being able to finally see her children for the first time—and enrolled in a court program for parents recovering from addiction. She began checking in with a judge via Zoom to report her progress, attending virtual therapy and parenting classes, and taking random drug tests. In October, she and Eric finally began seeing their kids for unsupervised afternoon visits. They used the occasion to treat their kids to McDonald’s, picking up the food in advance so they didn’t cut into play time together.

The first week in January, Stevie wept in her bedroom as a judge ruled over Zoom that her children could return home. “I can finally breathe,” she told me that evening, shortly after picking up her kids. “I feel like mom again.” Her calm confidence was barely recognizable from the hopeless weariness a few months before. In the background, her daughter excitedly ran around the living room before a dessert of Fruit Snacks.

In the coming months, Baltimore’s Department of Social Services will check in regularly on the family as Stevie and Eric readjust to caring for two kids. Their son, who celebrated his first birthday in February, has started walking. Their daughter, now 3 years old, alternates between doting on her brother and bullying him, hitting him, and stealing his toys. She throws tantrums when Stevie takes away her tablet and when it’s time for bed. Stevie isn’t sure if the meltdowns are a product of the upheaval of the past year or just the typical behavior of a rambunctious toddler.

Sometimes, when she’s in a timeout, Stevie’s daughter begins to cry, stretching her arms in search of a hug. When those little hands reach for her, Stevie finds it impossible to do anything other than scoop up her daughter and hold her close.

“I give her a little bit of slack because I don’t know exactly what she dealt with. It’s my fault they were gone, so I can’t be too hard on her,” Stevie says. “They were gone for so long.”