Mother Jones illustration; Getty

When a drunk motorist plowed into a Minneapolis protest against police brutality earlier this month—striking and killing one protester—multimedia journalist David Vance opened the Citizen app on his phone. Vance, who works for local NBC affiliate KARE, said he wanted “to get a better idea of what happened.”

On the app, Vance listened to audio from police scanners and watched videos posted by other users filming nearby. He received a prompt from the app, which sends incident alerts based on users’ location, asking him whether the scene was “still active.” Yes, he responded. Did he want to share live footage? Vance began filming, capturing the flashing red and blue lights of police cars, the small crowd behind the caution tape. Comments flowed in. He netted more than 4,300 views. His video was linked to a thread of other user videos of the scene, from various vantage points, and a timeline of updates about the victim and the police’s response.

It was as if Citizen and Vance were playing complementary roles in documenting the narratives of the city. Vance started using Citizen last year, when protests broke out in Minneapolis and across the country after the murder of George Floyd. He wasn’t alone. According to Google Trends data, the Citizen app reached its highest-ever search interest between May 31 and June 6 of last year, just a week after Floyd was killed, when protests were at their peak. In early June, Citizen topped Apple’s App Store as the leading news app, beating out the New York Times, Twitter, and Fox News. The state where it saw the most searches? Minnesota. The app saw a second spike among Minnesota users this April, the week protests erupted in Brooklyn Center and the Twin Cities in response to the police killing of Daunte Wright. Every person I spoke to for this piece noted that they first heard about the app amid last May’s protests.

Vance is the sort of reporter who listens to police scanners at home, but he says the app has been a helpful tool when he’s on duty, giving him quick notifications of whatever fire or other incident may be erupting nearby. He was resolute about Citizen’s positive role in protecting public safety—until he learned about the frenzied and wrongful detention of an unhoused man in Los Angeles who had a $30,000 bounty placed on his head by the app’s founder. That’s when he started to wonder if he and Citizen were really in the same business at all.

Citizen touts itself as the country’s premier public safety app. Using a mix of crowdsourced information like Vance’s videos and a fleet of in-house “reporters”—including former Daily Beast and New York Daily News journalists—who spend hours listening to police scanners and penning incident updates, the app sends alerts to what it says is a base of more than 7 million users in over 30 cities. Less than a week after its original release in 2016 under the name Vigilante, the app was pulled from the App Store for violating its guidelines prohibiting apps from “risking physical harm.”

Earlier apps didn’t survive criticisms that they posed an obvious risk of paranoia-fueled racial profiling. SketchFactor, where users could geotag incidents or items they found “sketchy,” launched in 2014 and shut down a year later. Ghetto Tracker launched and died in 2013.

But Andrew Frame, Vigilante’s CEO, a former teen hacker and early Facebook investor, decided to pivot, rebranding his startup as Citizen in 2017. The app swapped its masked defender icon for a watchful eye. Though the company is backed by more than $130 million in venture capital funding from the likes of Sequoia Capital, Greycroft, and billionaire Palantir founder Peter Thiel, Citizen is still searching for ways to make a profit. The app recently launched Protect, a $20-a-month service that allows users to speak to Citizen analysts over real-time video when they feel unsafe. In May, a Citizen patrol car was spotted on the streets of Los Angeles, though a representative for the company said it currently has “no plans to launch our own private security force.” Representatives told Vice the cars were part of a pilot program for its Los Angeles employees.

In an interview prior to the fire and manhunt, Frame spoke about the company’s mission to “democratize” information “now restricted to first responders” by sending it out to its users. “We don’t want you to download this app and have it scare you about your neighborhood,” Frame said. Rather, he hopes the constant alerts about fire trucks and police activity will help expose corruption, “put a spotlight on the bad policing behavior and the good policing behavior,” and bring out “the best in humanity.”

Jim Thatcher, an urban studies professor at the University of Washington, Tacoma, is skeptical. “If you give people this power to draw attention based around a dangerous event,” Thatcher says, “then they are actually encouraged to seek out, or at worst manufacture, these dangerous events,” noting the speed with which Citizen escalated the manhunt. Like many others, Thatcher downloaded Citizen during last year’s protests. He wondered whether it might be used as a tool for “sousveillance,” a term surveillance activists use in reference to turning cameras back on authorities. That didn’t shake out. “Let’s be explicitly clear here,” he says. “The ‘frictionless’ solution provided by a for-profit company for a public health and safety issue is just…not good. There’s no outcome where this ends well.”

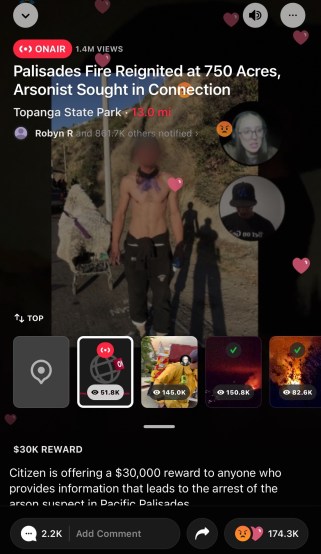

Indeed it didn’t. In mid-May, the company made headlines when a wildfire that broke out in Los Angeles’ Pacific Palisades neighborhood put the company’s service to the test. The hosts of Citizen’s new live-streaming program, On Air, asked users for information that would lead to the arsonist’s arrest. When the app received a photo of a “person of interest” through an “on-the-ground tip from an LAPD Sergeant,” according to its spokesperson, On Air blasted the man’s name and face across its networks for 15 hours, reaching nearly 850,000 users in the Los Angeles area.

Citizen’s OnAir broadcast offered $30,000 to tipsters about the alleged arsonist. Mother Jones has blurred the person’s face to protect their identity.

Screenshot by Cerise Castle/Citizen

According to internal Slack messages leaked to Vice, Frame, Citizen’s CEO, was gleeful at the opportunity—even as one staffer pointed out that the program was violating Citizen’s terms of service, which forbid posting identifying information about individuals involved in an incident. As fires edged closer to his Bel Air home, Frame upped the ante, first offering a reward of $10,000, then $30,000, to whoever could provide information on the man’s whereabouts.

In one frantic moment, he sent a Slack message to his team: “FIND THIS FUCK. LETS GET THIS GUY BEFORE MIDNIGHT HES GOING DOWN.”

“The more courage we have, the more signups we will have. go after bad guys, signups will skyrocket. period,” Frame wrote in another message. “we should catch a new bad guy EVERY DAY.”

According to its spokesperson, Citizen maintains that the “detainment of the person of interest was not a result of Citizen’s coverage,” and that this was the “first and only instance where these protocols were not followed.” The spokesperson says that Frame has taken the incident “very seriously and immediately audited and adjusted” company policies.

In any case, there’s more to Citizen than stoking people’s fears. In the aftermath of the fire, Citizen has ratcheted up its use of the On Air broadcast, which mimics network news crime coverage, mixing up the scaremongering (missing children) with the saccharine (pets reunited with families). In a recent segment, hosts spent nearly two hours alerting 40,000 Los Angeles users to help a young woman locate her stolen car, which contained a folder of documents about her birth parent. The car was found, although Citizen’s role in the recovery isn’t fully clear. In another, a member of Citizen’s street team searches for a man wielding swords in an alley, only to find a quiet, empty street; in yet another broadcast, a member walks down a street where it had been reported that people were knocking over e-scooters. (In both, the host, a man donning a snapback and AirPods, cautions viewers that these are “unconfirmed reports.”)

Frame says Citizen isn’t necessarily in the news business, but that “safety and news are very connected.” According to LinkedIn, the company employs more than a dozen “reporters,” many with backgrounds in traditional journalism. When Citizen opens in a new city, it contracts with these “street teams,” essentially users paid per post to film incidents: lost dog, stolen car, swordsman on the loose. These broadcasts aren’t as sensational as the Palisades fire manhunt, but they serve a key purpose—making the case for Citizen as a force for good and helping the app dominate a niche once filled by some of the local journalists it now employs. According to Wired, “street team” users aren’t identified within the app—Citizen wants the content “to feel organic.”

As we spoke, Vance, the Minneapolis journalist, had a change of heart. After learning about Citizen’s role in the Los Angeles manhunt, he no longer saw it as a platform compatible with his standards of journalistic integrity. “I don’t see what else it would be used for in its current incarnation—either vigilantism or sensationalism,” Vance said.

Hamid Khan, founder of the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, an anti-police-surveillance group, says the manhunt wasn’t Citizen gone awry; it was Citizen working as designed. Khan sees the app as part of a “culture of deputization and vigilantism” built on the “see something, say something” ethos of neighborhood watch, now “taking a more technological sort of spin.” He says tools like Citizen, with their patina of officialdom and impartial reporting, “are becoming a license to racially profile and go after some of the most vulnerable community members—particularly the unhoused—and to criminalize them.”

In 2019, my colleague Abigail Weinberg interviewed Steven Renderos, co-director of communications rights group MediaJustice, about Citizen’s risks: “If you happen to be someone who lives in a neighborhood where you think it is crime-ridden, it will reinforce that view,” Renderos said at the time. “Everything around us is trying to reinforce the belief that crime is an issue, that it’s continuing to happen and growing, and that’s just not the case.”

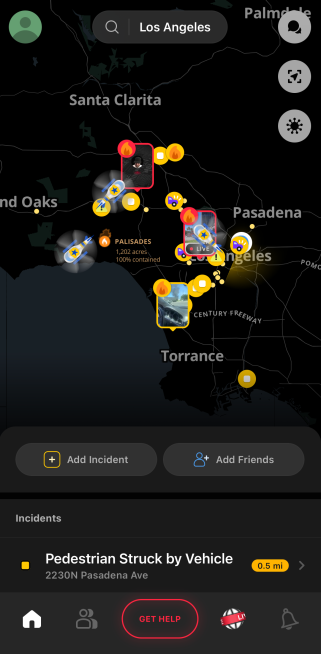

A screenshot of Citizen showing incidents in Los Angeles in June. Lil Kalish/Citizen

The app’s penchant for sensationalism, according to Khan, has real-life consequences beyond wrongly detaining one man. Khan argues that the growing nexus of “safety” apps and startups—Citizen, Nextdoor, Ring—has exacerbated the violent removal of unhoused people in Venice Beach, Los Angeles. (Nextdoor, like Citizen, saw a Google Trends spike the week of the George Floyd uprising that it hasn’t matched since.) Earlier this month, Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva dispatched deputies to the scenic ocean boardwalk to begin clearing out encampments, even though Venice is outside his agency’s jurisdiction. Nextdoor has become a site of organizing against reform-minded politicians like Los Angeles District Attorney George Gascón, with recall petitions against city council members (and Gov. Gavin Newsom) sandwiched between footage of encampment fires, alleged thefts, and break-ins.

Khan sees a direct line from 19th-century militias and slave-catching agencies to modern-day policing, all of which serve to create a “stalker state” in which “white supremacy is maintained,” race and poverty are policed, “land is secured and preserved,” and “undesirables” are removed from society.

Lisa Arellano, a professor at Colby College and expert on vigilante movements, says the pandemic has helped catalyze vigilantism. “People turn to various vigilante options” for two reasons, Arellano says: “One is this idea of unchecked criminality. The other is government failure.” Arellano, who has studied vigilantism on both the far right and far left, says vigilante movements succeed when they’re able to dominate the narrative on violence: who has the right to employ it, when, and against whom.

For Citizen, the pandemic couldn’t have arrived at a better time. As cities across the country debated police budgets following the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and conversations across party lines explored alternatives to the brute force of policing, venture capital promised to “democratize” public safety by giving anyone with a smartphone the ability to document their side of the story, surveil the neighborhood, summon help, and feel connected.

Under pressure to grow profitable, Citizen has had to make broader cases for its utility, and even necessity, through expansions like its broadcasting service—or its COVID contact-tracing app, SafePass, which has received official support in cities across the US. But the search data suggests that Citizen, and apps like it, owe some of their popularity to the fear of Black protest. What incentives does that create for “public safety” startups, and what kind of conception of public safety does it reveal? In any case, Arellano contends, it’s only a matter of time until Citizen’s May manhunt repeats itself—and ends in “some kind of ghastly violence.”