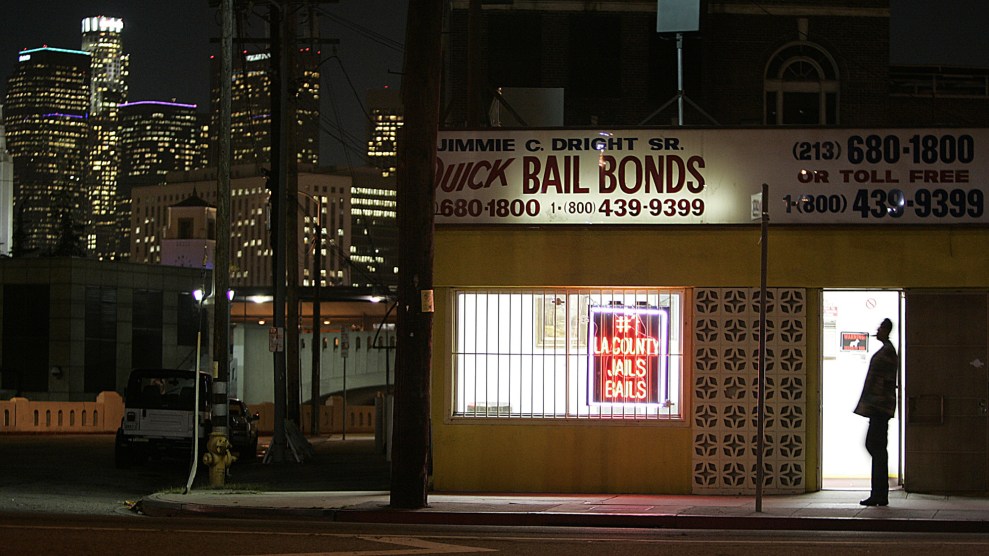

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Madison Pauly

Our criminal court system gives many people who are arrested two choices: stay in jail until trial or put down a certain amount of cash for bail. The latter option, originally intended to ensure defendants would show up to court, has been repeatedly shown to keep low-income defendants and people of color locked up at disproportionate rates, which incentivizes them to plead guilty and leads to harsher sentencing. States and local jurisdictions have been slowly shifting away from money bail for years. But before the pandemic, around two-thirds of the 758,000 people in jail nationwide on any given day still had not been convicted of anything. While a fraction of those had been deemed by a judge to be too risky to release, the majority simply couldn’t afford bail (the median for a felony is about $11,700) or a for-profit bond agent’s fee. Judges set bail amounts and other release conditions using a simple equation: flight risk + future danger to public safety.

The coronavirus changed that calculation. Jenny Carroll, a University of Alabama law professor and former public defender, explained that before COVID-19, the danger to public safety came from a defendant’s supposed chance of committing a future crime. But after the virus turned jails into hotspots, keeping a defendant in crowded jail became a more obvious risk to community safety. “COVID-19 really posed the possibility that for all of us to be safe, it might actually be better if we weren’t detaining as many people,” Carroll says, “if we weren’t keeping as many people in facilities where they couldn’t socially distance, where they couldn’t get access to medical care, where they couldn’t get access to personal hygiene products as readily as in the free world, where hand sanitizer was contraband.”

Some court systems responded accordingly. In March 2020, California’s Judicial Council attempted to reduce jail populations by issuing guidance for judges to set bail at $0 for people booked on misdemeanor or low-level felony charges. Top courts in Alaska, Kentucky, and New Orleans took similar steps. According to a survey conducted by the National Association of Pretrial Service Agencies (programs that analyze defendants’ risk levels to recommend pretrial release conditions), 60 percent of agencies reduced bail amounts in response to COVID, and 68 increased the use of personal recognizance bonds, which don’t require a defendant to pay. Meanwhile, more individual judges started choosing to set lower or no bail, according to Meghan Guevara, executive partner with the Pretrial Justice Institute. “COVID led more judges to exercise the discretion that they have available to them on a daily basis,” Guevara says.

After COVID, judges should continue to exercise that discretion, Guevara argues—but within guidelines that prohibit or reduce the option to impose financial conditions for release. Those kinds of limits could come from legislation like the Illinois law passed in February, which will abolish cash bail in the state entirely and establish a strict process for judicial decisions on whether to lock people up before trial. Following the pandemic, and the national uprising after George Floyd’s murder, Carroll predicts that the national conversation about pretrial release will increasingly center on the ways in which jailing people can harm community safety. “If my father is locked up, I lose the benefit of his company,” Carroll explains. “I lose the benefit of his financial support. I lose some stability. I may lose my house.” All that absence has consequences for community wellbeing.

The question of bail has become more acute since jail populations—which plummeted in the early days of the pandemic—are now rapidly rising, driven in part by court backlogs and police returning to pre-COVID arrest practices. Yet as more people are being booked into jail and come up before judges for pretrial release hearings, questions remain about whether money bail even serves its intended purpose. A study of Philadelphia, where District Attorney Larry Krasner stopped seeking cash bail for many crimes in 2018, found that defendants released without bail were no more likely to skip court or commit subsequent crimes than those who still had bail set. “The theory behind money bail is always, ‘Well, if you have skin in the game, you’re more likely to show up,'” Carroll says. “And when they took away that skin in the game, it didn’t make a difference.”