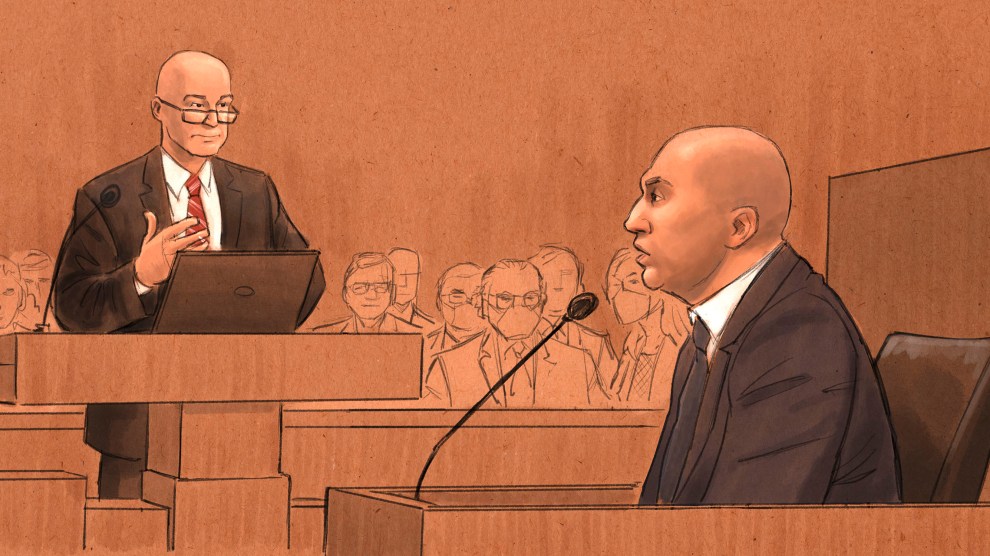

In a courtroom sketch, former Minneapolis Police Officer J. Alexander Kueng, right, testifies during his trial in the killing of George Floyd.Cedric Hohnstadt via AP

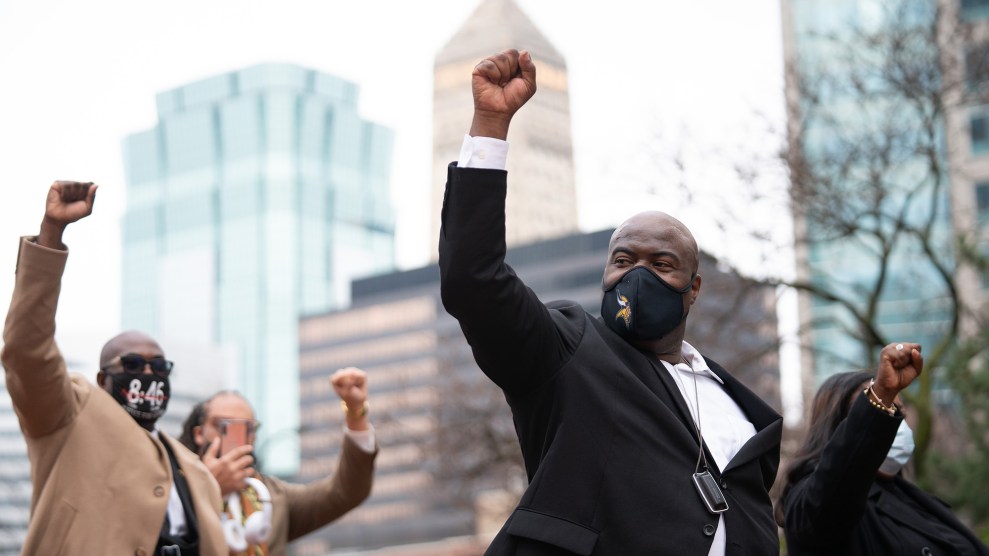

The three former Minneapolis police officers who were at the scene when Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd began testifying this week in a federal criminal trial, where they stand accused of violating Floyd’s civil rights.

While Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck, J. Alexander Kueng, a rookie cop, knelt on Floyd’s back. Another rookie, Thomas Lane, held his legs down. And a third officer, Tou Thao, kept bystanders back. None of them stepped in to stop the killing.

Now, two of the former officers are charged with failing to intervene against Chauvin’s unnecessary violence, and all three are charged with failing to provide Floyd proper medical care. Their defense lawyers argue that the Minneapolis Police Department provided inadequate training and taught them to follow orders from their superiors. Chauvin, who was convicted of murder and manslaughter last year, was the most senior officer there. “I think I would trust a 19-year veteran to figure it out,” Thao testified this week while explaining why he did not ask Chauvin to get off Floyd. Kueng, who had only been on the job for a few days, testified that field training officers like Chauvin served as a “role model,” and that his own training barely included any mention of the duty to intervene.

A conviction, which could mean prison time for the former officers, would likely have big ramifications outside of Minneapolis too. “This might be a rare occasion where a criminal prosecution will have an inordinate impact on how officers think about their jobs and how agencies think about their responsibilities,” says Georgetown Law Professor Christy Lopez, who spent years investigating police misconduct for the Department of Justice and recently co-founded a program that trains law enforcement to stop being passive bystanders when their colleagues act out of line.

It might sound like a simple goal, but “we underestimate how difficult it is for officers to intervene,” she says. I called her up this week to learn more about the challenges in getting cops to push back against their violent peers, and some of the ways this federal trial and other reforms might finally force them to take action.

Why is this trial important? And what precedent might it set for other police officers?

There have not been very many criminal trials regarding the failure to intervene. And this is the first criminal trial I’m aware of involving the failure to intervene by officers who are a lower rank than the officer they failed to intervene against. That’s important, because it signals a new emphasis on the responsibility of every police officer to prevent harm.

That’s interesting. Which prior cases involved a supervisor failing to intervene?

The most famous one was after [the police beat] Rodney King.

In Minneapolis now, what are the key elements that prosecutors will have to prove?

Generally speaking, with the duty to intervene under federal law, which has been a duty for over 50 years now, there’s a violation of constitutional rights. In some jurisdictions, that’s limited to the right to be free from unreasonable force. In other jurisdictions, it’s more broad. But in any event, the officer has to know or should have known that the right was being violated and has to have had the opportunity to intervene. And then you have to show that the officer failed to take reasonable efforts to actually intervene.

There might be some arguments, at least for one of the officers, Thao, that there wasn’t an opportunity to intervene. (In previous cases, courts have found officers didn’t have the opportunity to intervene when they were preoccupied with another suspect.) But that’s a very hard argument for these officers to make, given how long this incident lasted.

Still, I think the case is going to turn on whether the jury feels comfortable holding officers criminally liable for something a superior did.

And for Thao, do you mean he might argue he didn’t have an opportunity to intervene since he was kind of off to the side and had a different job, namely crowd control?

Exactly. From what we’ve heard him say it, it sounds like that’s going to be his defense.

Another one of the three officers doesn’t even face charges for failure to intervene, because at one point he asked Chauvin, “Should we roll [Floyd] on his side?”

Yeah, that’s Officer Lane. That’s an extremely mild intervention. I’m not even sure that legally counts as an intervention. But indeed, he was only charged with the failure to provide medical care.

Are there state laws or policies in place, in addition to the federal law, that require officers to intervene if they notice that someone’s rights are being violated?

There are often state laws, city ordinances, and police policies under their own general orders. And there are many, many more of those policies being passed at the state and local levels since George Floyd’s death. Minnesota actually had a statewide task force on police in-custody deaths just prior to Floyd’s death, and that report recommended state duty-to-intervene requirements, but I don’t think they were in place yet.

The federal duty-to-intervene requirement is via case law, and case law is just generally not detailed enough to provide the kind of regulation and oversight that state-level statutes can. This is why the state-level statutes and local law and even policies can be helpful.

But I just always want to make sure that journalists understand: Yes, we have these policies on paper, but we should not fool ourselves into thinking that’s very meaningful at all.

I’ve been doing this work for a very long time and I’ve seen these incidents at a lot of agencies all over the country since the ‘90s. And it is far too clear to me that policies alone simply aren’t enough. Officers don’t intervene when they should, just as other people in other industries don’t intervene when they should, and so we have to actually teach officers.

Why is it so difficult for them to intervene?

Some of the reasons are the same reasons people all over find it difficult to intervene: We’re afraid of being wrong. We come in late and we’re afraid we’re misreading the situation. We’re afraid that we’re going to be ostracized if we step in. A lot of those factors are especially salient in policing. And you know, especially if you’re new, if you’re a rookie, and you’re like, “Oh, maybe this is how it’s done. Yes, this is how they taught me in the academy, but this person has been doing this for 10 years, so maybe they know better.”

In policing, it’s a paramilitary structure, and it’s hierarchical. Policing is also a very insular, defensive profession. People need to feel like they have each other’s backs. People often feel like they are betraying their fellow officer if they stand up for someone who’s not a police officer.

Interesting. And as far as officers being nervous that they’re going to get in trouble if they intervene, does that happen very often?

It is absolutely a huge problem. It is the one actual inhibitor. Officers are retaliated against in formal and informal ways if they intervene and it’s viewed as a betrayal. You’re just seen as someone who won’t have the back of your fellow officers. And it can make life very difficult. There can be immediate retaliation, as we saw not too long ago in Sunrise, Florida, where a woman officer tried to intervene to keep the superior officer from pepper-spraying someone who was handcuffed. And the superior officer immediately turned around and grabbed her by the neck. You need a strong anti-retaliation policy and culture, and that’s the single most important thing to ensuring a culture of active bystandership.

You said training is important to teach officers how to intervene. Tell me more about that and the work you’re doing.

I began doing this work in 1995, before there were body cameras and before cellphones were ubiquitous. So when I was doing investigations of police departments, I was sitting here with a gazillion use-of-force reports and arrest reports trying to piece together what happened. And I remember on many occasions coming to the realization that there were many officers on the scene that could have done something but didn’t. But in the reports, they would either just be silent, or they would say somehow they didn’t see or hear anything. Then when body cameras and cellphone footage became more prevalent later, more people could see that, indeed, there were many officers who could have done something and didn’t.

When I was leading the investigation of the New Orleans Police Department with the DOJ, there was a very iconic civil rights attorney named Mary Howell. She brought to my attention the work of a Holocaust survivor named Ervin Staub who was, because of his experience, somewhat obsessed with this idea of what makes good people not step in and stop bad things from happening. He devoted his adult life to researching that question as a social psychologist, and he had come up with some very interesting research about people in a variety of contexts not intervening. There are examples of copilots not intervening to prevent a pilot from flying the airplane into the side of a mountain. And then in a much more common context, there are many examples of nurses and other people in operating rooms failing to intervene when they know the doctor is about to operate on the wrong patient or the wrong leg or the wrong organ and they don’t say anything. So hospitals have in fact started programs to teach people how to intervene.

So I was hearing all this, and Mary Howell and Ervin Staub had gotten together to talk about the application of this for policing. Long story short, we put a requirement into the [police] consent decree in New Orleans to provide peer intervention training. They developed a program called EPIC that teaches people the actual skills for how you intervene. It seemed to be impactful, but most people [in other cities] would say, “Oh, we already do that; we have a policy; we’re fine.” Then when George Floyd was killed, it focused attention on this issue. That’s when we launched the ABLE program, Active Bystandership for Law Enforcement. We’ve been training departments large and small all across the country, to instill a culture of active bystandership.

What are the skills you teach them?

One example is we teach them an acronym called PACT, which stands for Probe, Alert, Challenge, Take Action. In the George Floyd incident, what Officer Lane did was probing. He said something to the effect of, “Should we turn him over on his side?” If he had been trained in a more robust approach to active bystandership, he would have known that quite often probes work, but sometimes they don’t. And when they don’t, you have to ratchet it up to Alert. Like, “Hey, you need to move him on his side. It looks like he’s having a hard time breathing.” If that doesn’t work, then you say, “Either you turn him on his side, or I’m going to. This is not okay.” And then if that doesn’t work, then you actually take action, and you take Derek Chauvin’s knee off of George Floyd’s neck.

It’s often counterproductive if you go too quickly to take action. That can get you in trouble; it can lead to an ineffective intervention. Sometimes you need to [move quickly], like the officer in Sunrise, Florida, because there isn’t time: She immediately went to grab that officer before he pepper-sprayed the handcuffed person. But if you can, then you start earlier. Another thing that we teach people is the earlier the better, but better late than never, which was a key thing that could have helped in the George Floyd incident. Ideally, you do something before he is ever on the ground with a knee on his neck. But it’s never too late to act. And so we teach officers those sorts of ideas, and then we have them practicing. The muscle memory is important. And we try to encourage agencies to have a strong anti-retaliation policy.

Officer Thao was testifying, sort of as an excuse, that in his police training, he had been taught to use a knee to pin somebody down. Is poor training a valid excuse when you’re considering whether to hold somebody criminally liable?

That’s a great question. And a difficult question for me, in part because I think criminal liability is something that we don’t take seriously enough in this country. We’ve normalized it in a way that’s troubling. And so we should think hard before we hold anybody criminally liable for anything. I also think it’s a mistake to try to fix policing and these issues through each individual officer, through criminal prosecutions, civil lawsuits, or whatever: I really do believe we have to look at the systems and the responsibility of the agencies. Absolutely, Minneapolis PD should have been providing better training here.

I can hold that truth in my mind while also believing that it’s not an excuse for an officer to say, “Oh, well, I wasn’t trained. I hadn’t been taught the PACT acronym, so I didn’t know how to keep this from happening.” Officers know they have a duty. Any human being knows you shouldn’t sit there and watch one of your colleagues let someone die. The crowd was screaming at them not to let him die. I just can’t accept that it was acceptable for them not to intervene simply because they hadn’t received this training. But I hold that alongside my belief that if they had been trained, this incident may have turned out differently.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed.