Karen Wells and Andre Locke, the mother and father of Amir Locke, at a press conference in February at the Minnesota State Capitol, calling for the end of no-knock warrants.Carlos Gonzalez/AP

“I am not ‘disappointed,'” said Karen Wells, the mother of Amir Locke, on Wednesday after it was announced that there would be no criminal charges brought against Mark Hanneman, the Minneapolis police officer who shot and killed her son in a no-knock raid. “I am disgusted by the city of Minneapolis.” Locke was a 22-year-old Black man who, before he was killed, had planned to move to Texas to pursue a career in music and be closer to his mother.

Locke’s death was a violent rejoinder for the city. It came almost two years after Minneapolis was shaken by George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the same police department. In the massive protests and uprisings that followed, there were demands to fundamentally change policing. In the following contentious election season, city officials and politicians promised alterations—banning certain tactics, more trainings—but steered clear of supporting decreasing the funding of police, and actively campaigned against a ballot measure that would’ve made it easier to do so. They promised these reforms would work, but Locke’s death challenged the narrative that anything had actually changed.

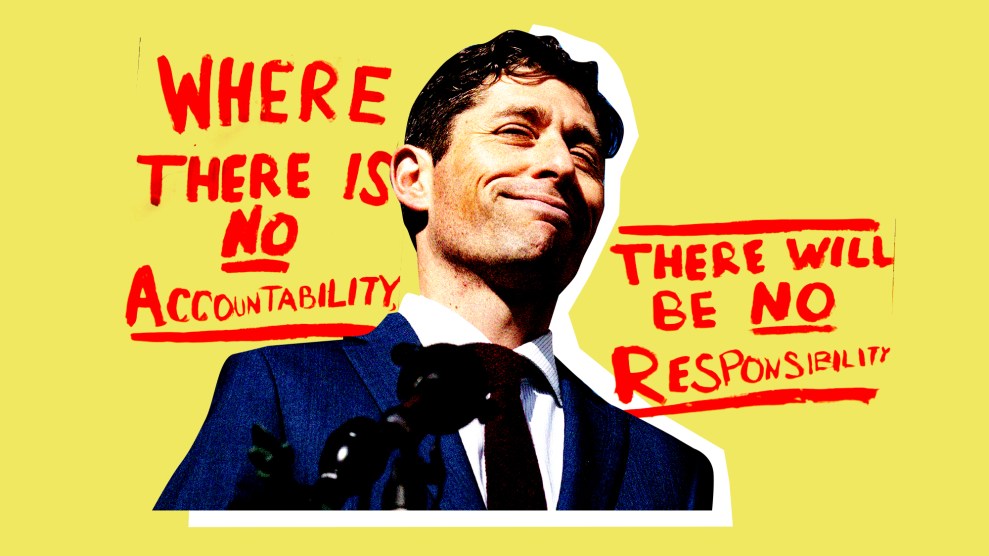

In fact, Amir Locke was killed in a raid tactic that the city’s Democratic mayor, Jacob Frey, had said he would ban in the wake of Floyd’s murder. Frey has falsely claimed to have “banned” no-knock warrants several times. On Tuesday, the night before the announcement of no charges for Locke’s killer, Frey again said he banned the practice. And again, it is not a full ban. (There are exceptions where cops can use no-knock raids.)

Wednesday’s decision was another reminder that for all the attention lavished on Minneapolis as a site of reckoning with racism and unaccountable police violence, it has become a microcosm for how little has been done.

When Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman and Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison announced their decision not to file charges against Hanneman in a joint statement, along with a press conference (and frequently asked questions page), they conceded they were horrified by the death. They outlined the details again. Locke had been sleeping on a cousin’s couch when a SWAT team burst through the door. He awoke to a group of loud men with guns charging toward him. He reached for his lawfully owned handgun and was immediately shot. Locke had not been named in the raid warrant. Wells, his mother, explained that Locke kept a gun with him for self-defense because he worked as a driver for food-delivery apps and was concerned about a rise in carjackings in Minneapolis.

Ellison and Freeman did not dispute that Locke may have been sleeping and startled by who he perceived as burglars, but the state use-of-force policy requires officials to “evaluate the totality of the circumstances from the perspective of a reasonable officer in a similar situation,” not from the perspective of Locke, the victim. Minnesota’s use-of-force statute 609.066 gives police officers tremendous latitude to shoot and kill you if they feel under threat. Because the officers were carrying out a search warrant for at-large suspects related to a murder case who were thought to have owned guns and committed violent acts, and because an “unidentified individual was holding a firearm pointed in the direction of at least one officer,” Hanneman’s use of force was that of an “objectively reasonable officer,” the joint statement said.

It should be quite obvious that the chances of a police officer feeling under threat would dramatically increase when they serve no-knock warrants, a euphemism for legalized home invasion (traditional “knock and announce” warrants aren’t much better, as my colleague Samantha Michaels has pointed out).

“With all of the available evidence, we would not be able to prove in court that Officer Hanneman’s use of force was not authorized under the law beyond a reasonable doubt. It would be unethical of us to file charges in a case in which we know that we will not be able to prevail because the law would not meet the charges,” Ellison said at the press conference.

Ellison continued, saying that despite the limitations of the law, there were things that could be done to prevent a situation like Locke’s from happening again—namely, that we need serious reform around the kind of no-knock warrants that led to Locke’s death and that have been under greater scrutiny nationwide since Breonna Taylor was killed in a similar raid in Louisville in 2020.

“We need to interrogate whether no-knock warrants are ever really needed. There are inherent risks for everyone involved,” Ellison said. Freeman agreed, adding that he had spoken with Locke’s family Wednesday and that they’re also “very frustrated” with no-knock warrants. “They, like us, believe that if a no-knock warrant hadn’t been used, Amir Locke might well be here today,” he said. In their joint press release, Ellison and Freeman wrote, “This tragedy may not have occurred absent the no-knock warrant used in this case.”

The problem is that the saga of banning no-knock warrants has been going on for years in Minneapolis. They have supposedly been “ended” multiple times. In another attempt to say this practice was over, on Tuesday, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey formalized a new policy on no-knock warrants—that the city put together with the consultation of DeRay Mckesson and Katie Ryan of the group Campaign Zero, who were hired by the city amid the scandal of Locke’s killing—and expects to implement it within the next month. The policy was initially announced on March 14.

But it’s not a complete end.

According to a statement on the city website, the new policy “prohibits the application for and execution of all no-knock search warrants by MPD.” It would also require officers to “knock and announce their presence and purpose prior to entry” for 20 seconds and 30 seconds if it’s between the hours of 8 p.m. and 7 a.m. (The warrant that led to Locke’s killing was executed at 6:48 a.m.) This is a policy improvement, but once again it’s been falsely referred to by several media outlets as a prohibition, ban, end, or some such word that communicates that no-knock warrants will never happen again in Minneapolis.

We can’t yet be sure of that, because the policy includes a loophole that the new regulations can be averted if there are “exigent circumstances” that include preventing imminent harm or providing emergency aid; preventing imminent destruction or the removal of evidence (excluding narcotics); when in hot pursuit; and preventing the imminent escape of a suspect. “If exigent circumstances arise that necessitate immediate entry or entry prior to the expiration of the required time of knocking and announcing, officers must thoroughly document the factors underlying that exigency,” the statement says.

Given the fairly wide range of interpretation provided by this stipulation, it’s unclear whether the warrant that led to officer Hanneman killing Locke would have met the criteria for “exigent circumstances.” After all, Minneapolis police officers aren’t particularly well-known for following rules to begin with, something Attorney General Ellison and County Attorney Freeman are intimately familiar with. Ellison came to prominence as an activist and civil rights attorney fighting against police brutality in Minneapolis, and Freeman, who is retiring this year, has been intensely criticized for his handling of past police shootings.

Shortly after Locke’s killing, the same thing happened: Frey announced a “moratorium” on no-knock warrants until they could roll out this new policy. (The temporary moratorium wasn’t actually an outright ban.) The problem was that Frey had claimed in his 2021 reelection campaign that he had already “banned” no-knock warrants. He later said that, throughout the campaign, his language “became more casual” and didn’t reflect the “necessary precision or nuance” of the earlier policy that he announced in November 2020, which introduced restrictions but was not an outright ban. (Sensing a theme here?)

In February, I wrote about how this was yet another example of the mayor’s duplicity and unwillingness to reform the Minneapolis Police Department, which is currently under federal investigation by the Department of Justice and somehow made off like bandits in its latest union contract.

In the midst of policy debates that follow these heinous acts of violence, it’s always important to keep front of mind the human toll. Karen Wells and Andre Locke remain a mother and father grieving without their son, Amir. Addressing officer Hanneman directly on Wednesday, Wells said, “The spirit of my baby is going to haunt you for the rest of your life.”