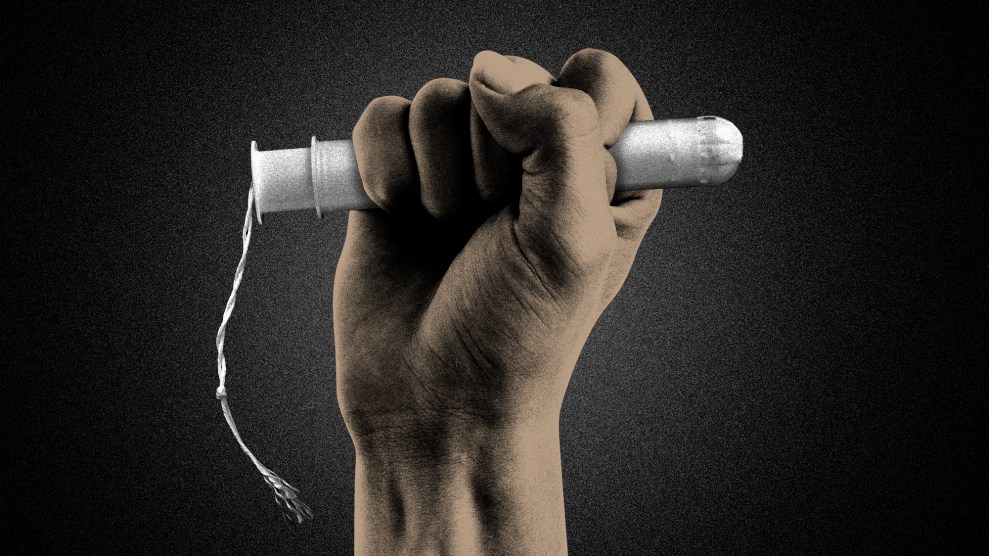

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Things were already hellish for pregnant people in prisons and jails. With the Roe reversal, it’s about to get even worse.

The United States incarcerates more women than anywhere else in the world, disproportionately women of color, and most of them are of reproductive age. An estimated 58,000 pregnant people are sent behind bars each year—the vast majority of them to jail, which means that many are still waiting for trial and haven’t been convicted of a crime but are too poor to pay bail. Some of them are innocent. Most are accused of nonviolent offenses.

And many of them want abortions, for various reasons. A Johns Hopkins study published last year examined pregnancy outcomes in four jail systems that allowed abortion during a 12-month period in 2016 and 2017. The researchers found that a whopping 33 percent of non-miscarriage pregnancies within those jails ended with abortions—significantly higher than the 18 percent rate of abortions in the free world. “[P]regnant incarcerated individuals, at least those entering jails, may actually have an increased need for abortion access,” wrote Dr. Carolyn Sufrin and the other Johns Hopkins researchers.

Even before the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade, it was tough to get the procedure in jails and prisons. Access to abortion during incarceration varies widely by geography, and even by facility. Some jails have long prohibited the procedure. And even in places where it’s allowed, there are hurdles: Under the Hyde Amendment, federal lockups can’t pay for abortions in most circumstances, leaving incarcerated pregnant people to foot the bill themselves. A lot of local jails and state prisons require them to pay out of pocket too, not just for the procedure, which averages hundreds of dollars, but also for the transportation to and from a clinic. Making matters worse, bureaucratic hoops and inaction by officers can force pregnant people in correctional settings to wait weeks or even months for their health care, a delay that sometimes pushes them past the legal limit for abortions within their state.

In prior years, some incarcerated people successfully sued to get quicker access to the procedure. In 2005, for example, a Missouri prisoner serving time for a parole violation went to court after officials blocked her abortion for weeks. Missouri’s assistant attorney general argued the prison had a legitimate interest in preventing the procedure because it didn’t want to allocate correctional officers to transport her. (In some states, even medication abortions aren’t allowed unless the doctor meets in person with the patient.) In court documents, the assistant attorney general denied that it was a problem to force a woman to give birth against her will. “Even if the result were plaintiff carrying her child to term, it ought not be held that this result—having a child—is a harm at all, much less an irreparable one,” he wrote. The US Supreme Court disagreed and sided with the pregnant prisoner.

But now, the landscape is totally different. After the Supreme Court struck down the constitutional right to abortion last month in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, paving the way for states to ban the procedure outright, many incarcerated women will no longer have legal recourse. And unlike pregnant people on the outside, they won’t be able to travel out of state for the health care they need. “You won’t have a choice,” says Pamela Winn, a prisoners’ rights activist and former nurse in Georgia who suffered a miscarriage in a federal jail in 2008. Some pregnant people may get out of lockup before their due dates, but by then it could be too late to legally obtain the procedure. Women on probation or parole are typically barred from traveling out of state, too—and there are about 200,000 of them just within the 13 states with abortion ban “trigger” laws. And for those stuck behind bars for long sentences, says Winn, there will be just one option: “You’ll have to be having that baby inside.”

That worries attorneys for incarcerated people, who point out that jails and prisons often provide abysmal health care and keep pregnant individuals in inhumane conditions. “Forcing people to carry pregnancies to term when they are in facilities that historically cannot address their medical needs is very disturbing,” says Corene Kendrick, deputy director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project. “Jails are the last place any mother would want to give birth to their child,” says Neisha-Rose Hines, who works at the ACLU’s affiliate in Florida. “It’s going to make an extremely unsafe, unsanitary situation worse.”

Winn, the activist in Georgia, knows about those unsafe conditions all too well. In 2008, guards at a federal jail shackled her to transport her to court while she was pregnant. A double chain wrapped around her belly and connected to her wristcuffs, and a chain dangled between her legs. As she stepped into the van, her tight ankle cuffs cut into her skin, and the pain caused her to misstep and fall, as she later testified in Congress. Afterward, she realized she was bleeding and requested a trip to the emergency room, but because of bureaucratic requirements she wasn’t allowed to go for seven weeks, and by then the ER doctors turned her away because the case was so old. Several more weeks passed, and while she was waiting to see an obstetrician for an ultrasound, she miscarried one night in her cell, by then five months’ pregnant. She began hemorrhaging, and as the blood pooled around her, correctional officers cuffed her wrist to the bed. “That’s how I endured the remainder of my miscarriage,” she told me, adding that she later learned that the officers threw her baby in the trash. “Then after everything I endured, they put me in solitary confinement,” she said.

There are plenty of other horror stories. In 2018, Diana Sanchez gave birth alone in her cell at the Denver County Jail, screaming in agony for hours without receiving help, according to a lawsuit she filed. After she told officials she was having contractions, nurses and jail deputies “chose to take a ‘wait and see’ approach to their care, as though it were not patently obvious to anyone—with or without medical training—that Ms. Sanchez was in labor and required immediate medical attention,” the suit stated. “Ms. Sanchez was forced to deliver Baby J.S.M. on a cold, hard bench, feet away from a toilet, in a jail cell at the Denver County Jail, all alone and with no medical supervision of treatment.” The city settled the lawsuit, paying her $500,000. In Georgia’s Clayton County, meanwhile, Tiana Hill also sued this year after she went into labor at a county jail and staffers delayed taking her to the hospital, allegedly because they thought she was having a miscarriage instead; the baby died days later.

Even in less dramatic scenarios, incarcerated pregnant people often don’t have the resources they need to thrive. Prison meals tend to be unbalanced, lacking in fruits, vegetables, and other nutritious food sources that can reduce the chances of maternal mortality, stillbirth, and low birth weight. “Most people who eat well in prison live off the canteen, which is an expensive way to live because the [food is] significantly overpriced,” said Brittany White, who was formerly incarcerated in Alabama and is now an organizing fellow with the Institute to End Mass Incarceration, based out of Harvard Law School. Dozens of states lack any policies about nutrition for pregnant women, according to an analysis by the Prison Policy Institute, a nonprofit. While many prisons provide prenatal vitamins, Winn, who was incarcerated in Georgia, said she was denied them during her pregnancy. Incarcerated people also have less control over their sleep, are limited in their time outside, and sometimes lack access to quality prenatal care. Miscarriages appear to be more common in jails than outside them, according to data collected by the Johns Hopkins researchers.

Around the country, activists have tried to introduce reforms. Winn wants Georgia lawmakers to pass a bill that would defer pregnant people’s sentences for 12 weeks postpartum, allowing them to give birth at home and bond with their babies. But no state has ever passed a measure like that, and it seems unlikely to catch on anytime soon. More commonly, dozens of states have enacted laws in recent years that limit or prohibit the shackling of pregnant people behind bars. But even after those laws passed, problems persist: The vast majority of hospital nurses surveyed in 2018 said their incarcerated pregnant patients were still shackled “sometimes to all of the time,” according to research published in the Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. In other words, correctional officers don’t always follow the rules. When pregnant people are in custody, even if they technically have rights, says ACLU of Georgia executive director Andrea Young, they are “completely at the mercy of the people holding them.”

Which brings us to a point that has not gotten enough attention since the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade. Republican lawmakers are seeking to ban abortions by criminalizing them, which would send many more people to prisons and jails because of the way they deal with pregnancies. But those same prisons and jails are not infrequently dealing with pregnancies in inhumane ways. And nobody, at least not among the Republican anti-abortion ranks, seems to care in the least.