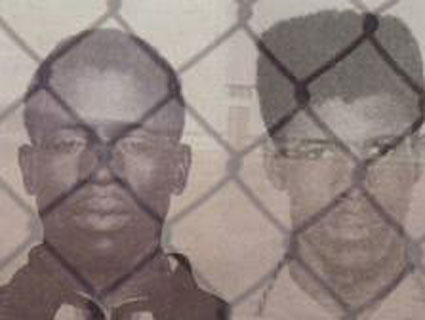

A cell at Angola where children will be housedCourtesy ACLU

In the coming days, Louisiana officials will incarcerate about two dozen children inside the old death row of Louisiana State Penitentiary, also called Angola, a massive maximum security prison for adult men that was once notorious for its violence.

Children as young as 10 with a history of assault may be transferred from their current juvenile correctional facilities to the former death row, where they will sleep in windowless cells with floor-to-ceiling metal bars that lock them in. The conditions are more punitive than those at the state’s high-security juvenile facilities, where kids normally sleep in dorms. The Office of Juvenile Justice will house the children at Angola temporarily while finishing construction on another place to detain them.

Several Louisiana law clinics and the ACLU sued to try to stop the transfers, arguing that keeping children at the adult prison—even temporarily—was unconstitutional and psychologically harmful, and that it might increase their risk of suicide. Though the kids will be housed separately from the adult men, the facility “is going to scream ‘prison’” to them, Vincent Schiraldi, a juvenile justice expert for the plaintiffs and the former commissioner of the New York City Department of Correction, told the court.

But on Friday, Chief District Judge Shelly Dick reluctantly signed off on the plan, stating that incarcerating kids at Angola would potentially be “traumatizing” for them, but that government officials had nowhere better to keep the kids, who pose security risks. “The prospect of putting a teenager to bed at night in a locked cell behind razor wire surrounded by swamps at Angola is disturbing,” the judge wrote. But “the threat of harm these youngsters present to themselves, and others, is intolerable.”

Kids at Angola will stay in single cells with metal bars and no windows.

Courtesy ACLU

In July, Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards announced the plan to transfer the children after several kids escaped from their juvenile facility and harmed other people. Six children who ran away from Bridge City Center for Youth carjacked a vehicle and shot the driver. Others started a riot at the facility that led to hospitalizations and damaged the building to such an extent that it could no longer house all the kids who required beds. “These youth have…become increasingly aggressive,” wrote Judge Dick, resulting in “severely broken bones, crushed skulls, [and] broken fingers.” State officials say they lack enough high-security housing for these children with a history of violence, and that keeping them at Angola is the only safe option at the moment.

“This solution is distressing and not without consequence,” the judge wrote, adding that it would have “deleterious psychological ramifications” for the kids. “That our society has such a choice to make is emblematic of grave underlying systemic social issues.”

Angola is the largest maximum-security prison in the country. It sits on former plantation land where Black people were forced to pick cotton before the Civil War, and in recent decades incarcerated men have continued to work in the fields for pennies an hour. The correctional facility was long notorious for bloody fights and beatings by guards. Today it is filled with many aging prisoners serving life sentences without the possibility of parole.

Children will stay in the prison’s Reception Center, just inside the gates and about a mile and a half away from the nearest housing unit for incarcerated men. The center served as the state’s death row until 2006. More recently, it held incarcerated women who were displaced from their prison during a flood.

During a tour of the building earlier this month, Schiraldi, the former commissioner of the New York City Department of Correction, observed conditions that he believed might traumatize children. Entering the prison gates, he passed coils of razor wire and a sign that read “Weapons Check In/Out.” The kids’ housing unit was surrounded by a fence, which state officials said they would wrap with “blackout” fabric “so that no one can see in or out,” to prevent the children from interacting with adult prisoners outside. In the lawsuit, attorneys for the plaintiffs wrote that “youth at Angola will live in single cells with floor-to-ceiling metal bars with no privacy, no windows, and open metal toilets.”

These conditions are overly punitive for children who are not even criminals, but are rather deemed “delinquents” and held in civil detention. “Arbitrarily transferring young people” to “a place with thousands of people convicted of crimes…is clearly punishment, which is not permitted for those who are civilly detained, and violates young people’s due process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment,” the attorneys wrote in their complaint. During the tour, Schiraldi saw visitation rooms with mesh barriers that previously prevented incarcerated adults from touching their family on the outside. “The fact that the planned OJJ facility at Angola is in the former death row is especially problematic from a psychological perspective,” the attorneys wrote, “and conveys messages of punishment and hopelessness rather than rehabilitation and opportunities for the future.”

A mesh barrier in the visitation area. State officials say they will not be used for children at Angola.

Courtesy ACLU

Others experts have protested the transfers. Last week, current and former youth correctional administrators wrote a letter to Gov. Bel Edwards expressing their dismay with the plan. “Angola is perhaps the most infamous prison in the country, and exists in our national conscience as a quintessential harsh, merciless, and dangerous place for adults who may never be free again,” they wrote in the letter, highlighted by the Appeal, a criminal justice news outlet. “This lore is not lost on the children that Louisiana is now planning to send there.”

Judge Dick said photos of the facility submitted by plaintiffs were “shocking and depressing,” but that state officials assured her they were renovating the grounds and would provide “a constitutional level of care” to the kids transferred there. Officials also said children at Angola would not be forced to visit their families through the mesh barriers, and that they could hug their parents. The judge said kids would receive the same educational services there that they they did at other juvenile facilities, with mental health counselors onsite during weekdays.

Though transferring children to Angola might pose psychological risks, the judge said she needed to consider the problems with keeping them at their current locations; state officials said some of them had terrorized other kids in juvenile detention, causing the others to fear sleeping at night, when they might be attacked. The state “has an obligation to protect all other youth in its custody,” the judge wrote.

But the kids on their way to Angola are terrified, too. The lawsuit was filed on behalf of a 17-year-old boy with post-traumatic stress disorder who may be transferred there after allegedly assaulting other kids and correctional staffers. After learning during a television news broadcast that he and his peers might be moved, the teen worried so much about conditions at the maximum-security prison that he struggled to sleep and began pulling out his hair, according to court documents. The judge acknowledged that placing him at Angola would likely worsen his PTSD. “I do not believe Angola is a place for any child,” his mother told the court, “and as a parent I strenuously disapprove of the decision to move my son and any other youth to a facility located there.” The transfers could start as soon as this week.