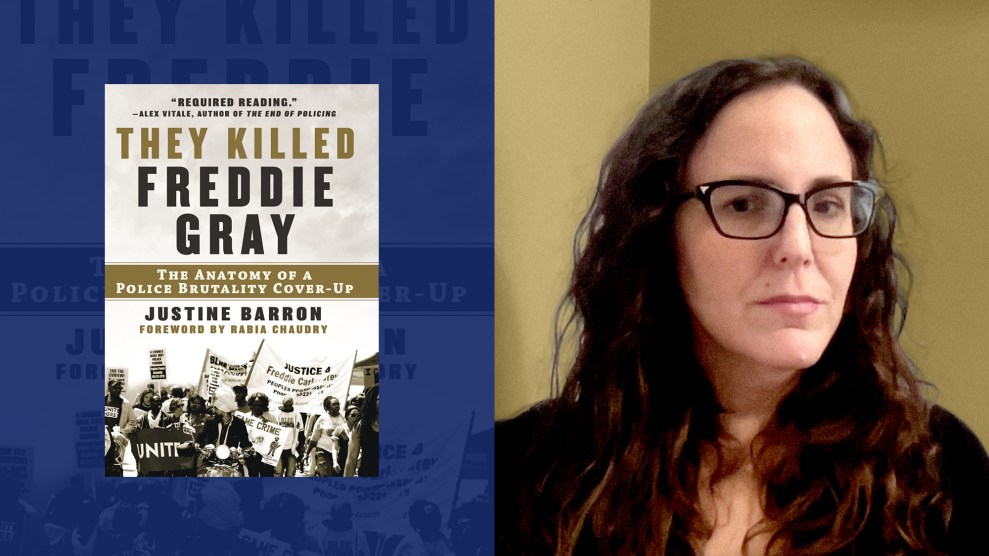

Mother Jones; Photo courtesy of Justine Barron

The initial narratives pushed by law enforcement after so-called “officer-involved shootings” or fatal beatings, particularly of Black men, have been found wrong many times over. In January, the Memphis police officers who beat 29-year-old Tyre Nichols to death claimed he’d been combative and reached for one of their guns. Video footage debunked both claims. In 2020, a press release from the Minneapolis Police Department, “Man Dies After Medical Incident During Police Interaction,” said an unnamed “suspect”—George Floyd—”physically resisted officers,” suffered “medical distress,” and “died a short time later.” It wasn’t mentioned that an MPD officer, Derek Chauvin, knelt on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes.

Official accounts of deaths in custody are regularly contradicted or complicated in similar ways—by witnesses, video recordings, and officers’ unexplored histories of misconduct—as in the case of Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old man from Baltimore’s Gilmor Homes neighborhood, who died in April 2015 after his spinal cord was fatally damaged in a police van. (Gray was arrested for possessing a knife permitted by Maryland law). His death, as Brandon E. Patterson wrote for Mother Jones later that year, “became a rallying cry for the Black Lives Matter movement.”

In her new book, They Killed Freddie Gray: The Anatomy of a Police Brutality Cover-Up, investigative journalist Justine Barron traces Gray’s killing, and the methods Baltimore police used to paint a narrative that didn’t line up with the evidence—a narrative media outlets amplified by focusing on an allegedly contradictory witness account and criticism of protests that followed Gray’s death.

Barron talked to me about her book, the importance of taking witnesses seriously, and the vital role crime reporting can play—when done ethically.

Why was investigating Baltimore police essential to understanding Freddie Gray’s killing?

When cases get attention, the Baltimore Police Department tends to invent a convoluted narrative and bury the evidence.

City leaders wanted the public to believe Gray’s death was an aberration, the result of a mysterious accident in the van, with Gray unrestrained and thrown forward while the van was making all of these stops. Rough rides do happen, but what my investigation reveals is that Gray’s death was a typical case of police using excessive force. Three officers picked him up and threw him headfirst into a narrow compartment of the van at the second stop, a reckless practice that still happens. At least nine witnesses saw it. BPD knew what happened at stop two early on. Prosecutors knew, too. Both agencies buried the evidence and kept it out of their public timelines, which alone is incriminatory.

Some media highlighted Gray’s previous arrests, but not previous misconduct by officers involved in his death. Why was it crucial for you to report on the misconduct?

Especially early on, the media used court records to tell the story of Freddie Gray instead of interviewing his friends and neighbors. News outlets circulated a long list of his arrests as if it were a character trait. But there were duplicated records, and half of his arrests were dropped by prosecutors for lack of probable cause.

On the other hand, you have Lieutenant Brian Rice, who led the chase and arrest of Gray as well as the cover-up of what happened. Police disciplinary files weren’t available to reporters or the public in 2015. Rice’s files show that his career started with a complaint about him knocking a young man with a broken arm unconscious and facing no discipline. There were more than 30 complaints against him for violence, harassment, abusive language, and more; only one was determined unfounded. There were suspensions and complaints even from his own supervisors.

The Guardian did report on complaints against Rice for harassment and abuse of his ex-girlfriend and her husband. Rice’s friends in the FOP convinced some local media that these “personal” issues were unrelated. Rice would harass local police, ignore their commands, and generally act recklessly. So if you laid the probable cause statements from Gray’s arrests next to Rice’s disciplinary files and police reports, you might have a different take on which one was more dangerous to the public. The public only heard about Gray’s arrests.

Let’s talk about narratives. How did the Baltimore Police Department rely on the media to feed out information?

News outlets reproduced maps and timelines to support the police narrative of the van’s journey, without evidence to support all of it. The mayor told the public that Gray’s injury must have “happened in the van” while it was moving—a claim for which there was no evidence at the time—and the media immediately published story after story about “rough rides.”

There was one week, at the end of April, where the coverage was especially problematic. Almost every day, the media reported another anonymously sourced story as to how Gray was killed—banging his own head, hitting a bolt in the van, and so on. All of the stories turned out to be false, but major news outlets claimed they came from valid sources.

Years later, when BPD finally released some actual evidence, the media had moved on and ignored it. It’s amazing to me that crime journalism is still so much in the business of repeating what police say. I see crime reporters get lied to year after year, find out they were lied to, and continue going back to the police well for stories.

Was there anyone you talked to who you were surprised not to see in local media coverage or trials?

There were about 20 or so witnesses who reported seeing and hearing police violence at the first two stops of the van ride. The witnesses were ignored or marginalized by police investigators, prosecutors, and most of the media.

My book is especially grounded in statements witnesses gave investigators in the hours and days after Gray’s arrest. These statements never saw the light of day and weren’t shared with the medical examiner. They credibly describe police using excessive force both before and after the video that went viral of Gray’s arrest. The witness statements are credible because they’re filled with accurate details that weren’t made public yet, but could be verified by audio and video—like the exact movement of the bikes and police cars at the scene and the dialogue people were having.

The media did highlight some witnesses early on, but usually in brief soundbites. Then Gray died and police took control of the narrative. BPD denied evidence of force. Media mostly stopped reporting on the witnesses after [then-State’s Attorney] Marilyn Mosby’s charges [against six Baltimore officers].

Your initial reporting was for the podcast Undisclosed’s series on Freddie Gray. Can you talk about doing thorough research in the era of true-crime podcasts?

Thorough research means treating every part of a police account of an in-custody death skeptically until it can be verified. Police are incentivized to lie and practiced at it. What Undisclosed and other true crime podcasts and books have done is open the investigatory gates. As a result, more cases are being solved.

True crime podcasts and shows should make more room for stories of deaths in police custody. There is some racism in the true crime universe. I want there to be podcasts about what really happened to Sandra Bland, Alton Sterling, and others—not just narrative but investigatory. Someone is sitting on evidence in those cases like what I finally obtained in the Freddie Gray case.

Could you tell me about steps you took interviewing witnesses and people who knew Freddie Gray, knowing the impact bad reporting may have had on them?

All of the witnesses I spoke with over the years were traumatized by watching Gray’s arrest and still feel the pain of it. Several of the older witnesses described experiencing restless sleep for years.

Some of the younger witnesses did not want to talk at first. They were burned by reporters and by Mosby promising them accountability. They had layers of trauma. Some were harassed or arrested by police.

In my case, it wasn’t hard to affirm the witnesses who did speak to me, because I had already put together so much of what happened and I knew what they had been through. It wasn’t hard to be respectful and empathetic.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.