The first time Katrina Edwards was locked in a psychiatric hospital for children, she was sure a foster parent would pick her up the next day.

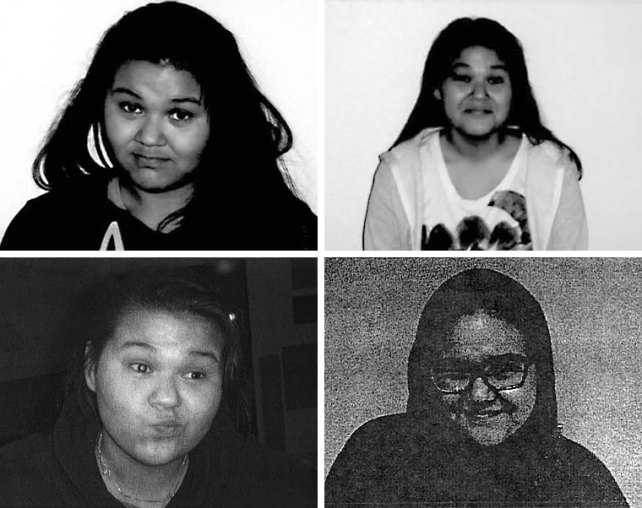

It was a spring night in 2012 when Edwards, then 12 years old, was admitted to North Star Behavioral Health in Anchorage. In a photo taken upon her arrival, Edwards wears an Abercrombie hoodie and has dark circles under her eyes, her expression skeptical. During her initial evaluation, a psychiatrist asked a battery of questions, including what Edwards wanted to be when she grew up (a police officer), what she did for fun (sports), and how she slept (poorly, with nightmares).

Alaska’s Office of Children’s Services had put Edwards in foster care earlier that year after she reported being sexually abused by her mother’s boyfriend. Asked why she’d ended up at North Star, Edwards explained that she had threatened to run away from her foster home and commit suicide. Medical records from her admission noted that she had a history of fleeting suicidal ideation, but that Edwards said she didn’t have a plan or intention of killing herself.

Then, the psychiatrist asked, if Edwards had three wishes, what would they be? Instead of talking about her dreams for the future, Edwards focused on the past: She said she wished that she hadn’t been abused, that she hadn’t been sexually abused, and, pointedly, that she hadn’t threatened suicide.

Edwards sobbed and yelled in protest as she handed over her cellphone and jewelry and changed into blue scrubs and hospital socks. She refused to sign the admissions paperwork; an OCS caseworker did so instead, according to court documents. Her outburst continued as a staffer ushered her into the unit for adolescent girls.

“If you keep acting like this,” one girl warned her, “you’re gonna get booty juiced.”

In the days to follow, Edwards learned the facility’s peculiar vernacular. “Booty juice” was the intramuscular sedative that staffers gave to kids they thought were acting out. According to court documents, they would restrain children and pull their pants down to administer the injection, then seclude them in the small, unfurnished space known as the “quiet room.” If someone in your unit got into a fight, or if you refused to take your medications, you could be put on “unit restriction,” unable to leave the dormitory area to go to the cafeteria, classes, or the fenced-in basketball court outside.

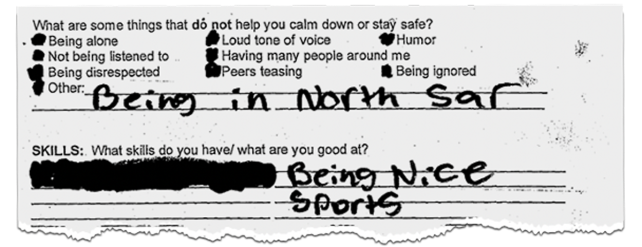

How was it possible, Edwards wondered, that passing thoughts of suicide had landed her in a “mini prison for children”? She says that when she mentioned suicide to her foster mom, she hadn’t meant it literally; she’d meant that she felt miserable and wanted someone to sit down and listen to her. The chaos of the facility felt like the opposite of what Edwards needed. A few weeks into her stay, she filled out a “personal de-escalation plan.” It asked, “What are some things that do not help you calm down or stay safe?” She checked all the boxes on the sheet: things like “loud tone of voice” and “being ignored.” She also wrote in her own answer: “Being in North Star.”

Now 23, Edwards has a round face, a quick laugh, and an unfiltered way of speaking that’s disarmingly charming, even if she’s telling you that you’re an overcautious driver and that you’ve had something in your teeth all day—which she did, the first time we met. She giggles while telling traumatic stories. In those first days at North Star, she banged on the windows, hoping to be rescued. “When people would walk up, I’d be in the window, thinking they could see me cry for help,” she explained with a laugh. “They couldn’t see me at all.”

Edwards was released after 24 days. But just two weeks later, she was back—this time in a police car, after reportedly making suicidal comments. Noting Edwards was “agitated and prone to threaten others,” a psychiatrist prescribed Seroquel, a potent antipsychotic. Twenty-eight days later, she was released, and by February 2013, she had run away, again had been picked up by the police, and again was deposited at North Star.

This time, she repeatedly attempted to escape. Over the course of two weeks, she was put in the quiet room three times, restrained twice, and forcibly injected once—for pulling a fire alarm in an escape attempt, according to medical records. She vividly recalls being held down, a male staff member’s knee on her back as she was injected, the panic and confusion she felt when waking up in the quiet room.

The psychiatrist increased Edwards’ Seroquel prescription; she was also taking Concerta for ADHD, Benadryl for “agitation,” melatonin for sleep, and the antidepressant Lexapro. At times, Edwards pleaded to stop the meds. “They are messing up with my body,” she told her psychiatrist, according to medical records. “They are messing up with my mind and sometimes I don’t even know what I’m doing.”

A month into her stay, Edwards was moved from North Star’s hospital to its psychiatric residential facility, a locked unit for longer stays. From the unit’s window, she stared out at a bank on the other side of a parking lot, imagining the lives of the customers—their baby mamas, their paydays. For a time, Edwards shared a room with a girl who talked to “Sally,” her hallucinated friend who visited their dorm.

OCS turnover was so common that Edwards often didn’t know who her caseworker was, but on the rare occasions they spoke, Edwards begged to go anywhere else. According to Edwards, North Star staffers told her she’d have to wait for a foster family to become available. “They would tell me, ‘Oh, you’re only gonna be here for a month,’” she said. “And then a month would go by, and they’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, we got to extend it for like another month.’” Medical records show that Edwards’ discharge was pushed back on at least two occasions because OCS couldn’t find a home for her.

Edwards celebrated her 13th birthday at North Star in March, and her 14th a year later. She remained in the facility for 18 months.

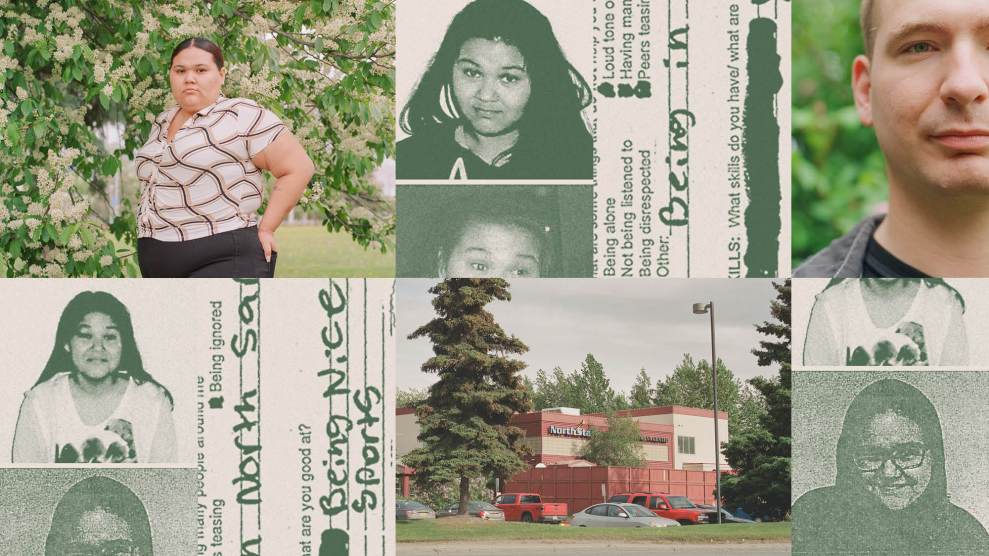

Photos of Edwards taken on admission to North Star. She spent more than two years at the facility between 2012 and 2017.

North Star is owned by Universal Health Services, a publicly traded, Fortune 500 company that is the nation’s largest psychiatric hospital chain, with 185 inpatient behavioral health facilities and dozens of acute care hospitals across the country, in addition to centers in Puerto Rico and the United Kingdom. More than 21,000 inpatient psychiatric beds—or one in six across the country—are operated by UHS, which brought in $13.4 billion last year.

In recent years, the company has been the subject of several high-profile lawsuits and investigations, including a blistering BuzzFeed News series in 2016 and a Department of Justice probe that resulted in $122 million in settlements in 2020. The claims of these investigations bear a striking resemblance to Edwards’ experience: UHS facilities admitted patients who didn’t need to be there to begin with, failed to provide adequate treatment and staffing, billed insurance for unnecessary services over excessive lengths of time, and improperly used physical and chemical restraints and isolation. BuzzFeed reported that some of the company’s psychiatric hospitals used suicidal ideation to “justify almost any admission”; in 2013, UHS hospitals submitted Medicare claims for suicidal ideation at more than four times the rate of non-UHS psychiatric hospitals.

In a statement, UHS denied BuzzFeed’s conclusions and disputed the DOJ’s allegations, noting that the settlement agreement “is not an admission of liability.” The company said it complies with regulations related to “restrictive practices” and is committed to reducing the use of restraints and seclusion. (Read the statement here.)

Politicians on both sides of the aisle have decried the company, and Sens. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) launched an ongoing probe into UHS and other operators of residential facilities for kids in July 2022. Celebrity heiress Paris Hilton—who experienced physical and sexual abuse as a teenager in the 1990s at Provo Canyon School, a Utah facility since bought by UHS—took aim at the company as part of her advocacy work against the so-called troubled teen industry.

Despite all this scrutiny, a large, highly profitable, and easily exploitable group of UHS patients has been overlooked: foster children. A yearlong Mother Jones investigation shows that thousands of foster kids have been admitted in recent years to UHS’s psychiatric facilities, where they typically stay for weeks or months, sometimes leaving far worse off than when they arrived. Foster children provide a lucrative patient base for the same reasons they’re so vulnerable: There’s rarely an adult on the outside clamoring to get them out, and often, they don’t have anywhere else to go. Plus, Medicaid typically foots the bill, which at North Star costs $938 per night. As Edwards notes, “They got a lot of money from me.” (UHS disputed the allegation that many children get worse in its care, pointing to its positive clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction scores.)

Over time, a symbiotic relationship has developed between overburdened child welfare agencies, which have too many kids in custody and not enough places to put them, and large, for-profit companies like UHS, with beds to fill and profits to make, says Ronald Davidson, a psychologist and the former director of the Mental Health Policy Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Over the course of two decades, until 2014, Davidson and his team reviewed hundreds of psychiatric facilities across the country as part of a consent decree intended to reform Illinois’ child welfare system. He also conducted similar reviews as a DOJ consultant. “The sales pitch—‘We can offer solutions to your overwhelming caseloads of high-needs children’—appeared irresistible to frantic agencies in need of more beds,” he explains, “and many of them desperately took the bait.” Kids often come back to facilities again and again, acting out more with each admission. “Unfortunately, in many hospitals, the door only swings one way,” Davidson says. “You become a patient, and you stay a patient.” To UHS and its competitors, he concludes, foster kids are “a gold mine.”

For some foster children, the results have been devastating. As Edwards endured her stay at North Star, a 12-year-old West Virginia foster child was placed at UHS’s Cedar Grove Residential Treatment Center, a program in Tennessee for sexually abusive and reactive boys, even though he wasn’t a sex offender. He begged his caseworker to let him leave but was held at the facility for 18 months, according to a subsequent lawsuit against the state’s CPS agency. In 2018, Oregon CPS sent a 14-year-old girl to Provo Canyon School, where she experienced 42 instances of peer assault, seclusion, or restraint—including being forcibly injected with the antipsychotic Haldol 17 times—over the course of three months, according to records obtained by state officials. The same year, Virginia’s CPS agency sent 17-year-old Raven Nichole Keffer to UHS’s Newport News Behavioral Health Center, where she collapsed after days of complaining of feeling sick. According to a lawsuit, a 15-year-old patient was the first to call 911; Keffer died of an allegedly preventable adrenal insufficiency. In 2021, Alabama CPS placed a 10-year-old at UHS’s Alabama Clinical Schools, where he was repeatedly assaulted by staffers over six months, resulting in a broken collarbone and black eye, in addition to being bitten by scorpions in his bed “many times,” according to a recent lawsuit. When he reported the injuries, staffers allegedly threatened to kill him.

In its statement, UHS noted it couldn’t comment on ongoing investigations, pending lawsuits, or specific patients, though it did say the incident at Newport News “was the only death of a patient while in the care of the facility.” The statement added, “Our facilities are highly regarded, trusted providers of behavioral health services in the communities we serve.”

Last year, when a lawyer in Alaska offhandedly mentioned that OCS uses North Star as a “dumping ground,” I started talking to foster kids about their experiences at the facility. I was struck by the similarities in their stories: the frequency of restraints and booty juicing; the panic of being sent to the quiet room; the claims that a caseworker or staffer said they were only there because they were waiting for a foster home; even the banging on the double-paned windows. The problem transcends Alaska or UHS. As many lawsuits have documented, child welfare agencies across the country rely on locked psychiatric facilities, many of which use punitive disciplinary tactics, to house difficult-to-place kids. These placements disproportionately affect children of color. Black and Indigenous kids—including Edwards, who is part Yupik—are more likely to enter the foster system and more likely to be sent to residential treatment facilities.

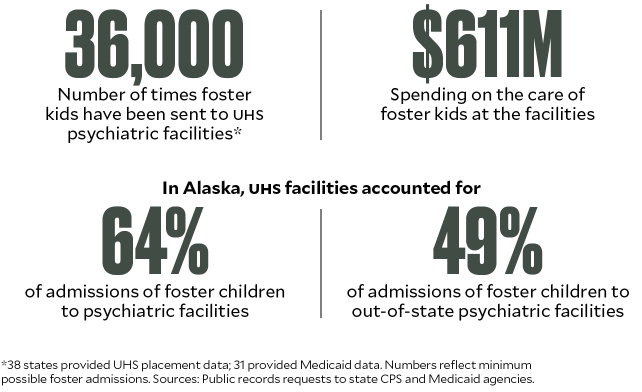

To understand just how big an impact UHS has on the lives of foster kids, I combed through thousands of pages of court filings and medical records, and interviewed more than 50 former UHS employees, patients, child welfare experts, lawyers, and policymakers. I also filed public records requests to the CPS and Medicaid agencies in all 50 states, asking for the number of foster children sent to the company’s inpatient behavioral health facilities and the amount of money spent on their care. (No national database exists.) The 38 states that provided data sent foster children to UHS facilities more than 36,000 times between 2017 and 2022. Meanwhile, the 31 states that responded to my Medicaid query spent more than $600 million on the treatment of foster children at UHS facilities over the same period.

The data shows that child welfare agencies routinely send foster children to UHS programs already implicated by damning inspections and media reports. Hundreds went to Provo Canyon, whose license was threatened twice after children escaped or were injured during physical restraints. (UHS noted Provo Canyon School resolved concerns with state inspectors in a timely manner.) Hundreds more went to Hill Crest Behavioral Health Services, where internal videos revealed by BuzzFeed in 2017 showed staffers repeatedly beating and dragging young patients, to the condemnation of members of Congress, and to North Star, where federal investigators last year reported escapes, assaults, and a patient not receiving a single therapy appointment for 40 days.

“It does kind of make your head spin,” said Davidson, when presented with the data. “It is a huge, huge market, dollarwise. And the thing that irritates advocates and people like me is that so much of this marketplace is either unnecessary or patients could far more easily be treated at far lower cost in outpatient care.”

By February 2015, Edwards had spent a total of 722 nights at North Star—a stay that cost the state an estimated $330,000. For Edwards, the years collapsed into one long, medicated blur. Recalling her experience there, she says, is “like explaining what happens when you get into a fight, and you don’t know how you got the bruises on your body.”

Back in 2020, North Star’s Haley Morrissey had a clear sales goal: “Get numbers up and make sure census was at capacity.” That meant spreading the word about the treatment center to 120 people each month. As part of a five-person team of “clinical community liaisons,” Morrissey contacted police officers, first responders, and emergency departments, alerting them when North Star had open beds and reminding them that prospective patients could always get a free assessment. She met with school counselors across southeastern Alaska. Her team sent care packages to OCS offices with North Star–branded mugs, stress balls, and lip balms, thanking them for their work. Organizations with particularly high referral rates to North Star received bath bombs and cards reminding the recipients to practice self-care.

Morrissey spent nearly a decade working at North Star, including time as a recreational therapist. She took pride in helping provide much-needed mental health services. Her enthusiasm dimmed, though, as she became increasingly alarmed by the understaffing and unsafe conditions. Foster kids, sometimes called “frequent flyers” by the staff, tended to come back. A bright-eyed 8-year-old on the children’s unit would turn into a slightly more aggressive kid on the preteen unit and then become an apathetic, angry teenager on the adolescent unit. Eventually, Morrissey decided to resign, leaving North Star last fall. Her message for families today is a far cry from when she was on the road marketing North Star: “Absolutely do not send them there.”

Alaska perfectly exemplifies the way UHS profits from failing foster care systems. More than three times as many kids are in foster care as there are licensed foster homes, a problem some critics attribute to too many children being removed from their families to begin with—particularly Alaska Native kids, who make up two-thirds of the state’s foster children. A quarter of OCS caseworker positions are empty; more than half of caseworkers leave each year. Meanwhile, behavioral health resources for kids are so lacking that the DOJ recently concluded the state is violating the Americans With Disabilities Act.

It’s no wonder, then, that foster children have been admitted to North Star, the state’s only private psychiatric facility for kids, more than 500 times over the past six years, or that foster kids are routinely sent to similar programs out of state. Two of every three admissions of Alaska foster children to psychiatric facilities occurred at those owned by UHS, including half of out-of-state placements. From 2017 to 2022, the state’s Medicaid program for children paid North Star $119 million.

But the spending doesn’t stop there: OCS data shows that the agency pays for kids to stay at North Star even when Medicaid reviewers have determined it’s not medically necessary. Between 2017 and 2020, the agency paid North Star more than $1 million for the care of foster children whose stays weren’t covered by Medicaid.

Of the many lawsuits involving OCS and North Star over the years, the case of a “frequent flyer” named Nathon Pressley stands out for laying bare their mutually beneficial relationship. Pressley entered the foster system in 1998, when he was a year old, and bounced from foster home to residential facility to foster home for 17 years—his entire childhood. He cycled in and out of North Star starting when he was 5, ultimately spending a cumulative 429 days there.

Sometime after his last North Star stay, Pressley went to a retreat organized by Facing Foster Care in Alaska, an advocacy group for foster youth. At a church on the outskirts of Anchorage, he met Jim Davis, the co-founding attorney of the Northern Justice Project, a civil rights law firm. Davis had recently had his own awakening at one of the retreats, hanging out with foster youth, mostly teenagers, eating pizza at the church. The kids seemed “basically normal,” Davis remembers—they reminded him of his own kids. “And then a lot of them started talking about North Star, and how they were institutionalized at North Star, and how they were forced to take drugs at North Star.”

This was news to Davis. “To be honest with you, I just remember leaving and thinking, maybe these foster youth are exaggerating everything,” Davis says. “It just seemed too far-fetched.”

But once Davis dug into foster care records, he was convinced. In 2017, Davis represented Pressley in a lawsuit accusing OCS of negligence; OCS, in turn, sued North Star in a third-party complaint, arguing that, if Pressley had been harmed, North Star was partially at fault. In her deposition, then–OCS director Christy Lawton said that foster children stay at North Star—even after Medicaid stops paying—when the agency can’t find a “safe, appropriate discharge placement.” In the foster system, she admitted, “there often can be cases that end up languishing.”

Lindsay Bothe, an OCS manager who was an expert witness in Pressley’s case, acknowledged in her deposition that Pressley “did have some longer stays while they were looking for a placement for him to discharge to.” Davis then pressed Bothe:

Davis: Nathon didn’t really belong at North Star anymore because he didn’t meet that level of care, and he was already stabilized, at least as far as North Star goes, but there wasn’t anyplace else with the right level of care to put him?

Bothe: Correct.

Davis: So he just stayed locked up in a psychiatric facility?

Bothe: Yes.

Davis: For months.

Bothe: Yes.

OCS and North Star settled with Pressley last year for an undisclosed sum. In a statement, OCS said finding suitable placements is a “nationwide challenge,” and that it strives to do so promptly.

Former North Star staffers told me that the problem wasn’t just that kids stayed too long, but that they were admitted at all. Jason Fedeli, who worked as an intake coordinator and counselor until 2020, repeatedly saw cases in which children would end up at North Star after having an argument with their foster parents. Fedeli interviewed kids who he didn’t think needed a locked psychiatric hospital. But again and again, they were admitted. He often saw them get worse rather than better, in part because the facility was so understaffed. When Fedeli became a therapist, he says he was spread so thin that “therapy” often amounted to five-minute check-ins during which he would ask, “How’re you doing? You feeling good? Are you suicidal?” Staffers would call such encounters “flybys.” (UHS denied that its facilities operate with inadequate staffing levels, adding that admissions are based “only on the patient’s clinical presentation.”)

Eventually, North Star dismantled the discharge planning team, and this, too, became Fedeli’s responsibility. He learned that there were plenty of places out of state—particularly in Utah—that would take struggling children. Medicaid covered a child’s out-of-state stay only if they first had been denied by three Alaska facilities; when staffers wanted to send a child to the Lower 48, they would “go to three places that you knew would deny the child,” Fedeli said, “and just mark them off your list. Or you’d even call them up and be like, ‘Hey, we just want a denial.’”

This may help explain why so many foster children who stayed at North Star said that staffers proposed out-of-state transfers. “They kept trying to bring me to Utah,” said Alexies Ezell, who attended North Star three times. “Every single time I was brought there, it was fucking Utah. I was like, What is in Utah?”

Katrina Edwards would find out. In 2015, shortly before her 15th birthday, Edwards received news: She was being moved from North Star, where she’d lived for two years, to Copper Hills, in West Jordan, Utah. Plane tickets had already been bought. She had never been out of state before. Everything about Copper Hills—the climate, the terrain, the people—was unfamiliar. But Copper Hills did have something in common with North Star: It, too, was owned by UHS.

Founded in 1979, UHS traces its origins back a decade earlier, when Alan Miller—a Brooklynite, veteran, and Wharton School of Business graduate—was working at an ad agency. One day, an old Wharton roommate approached him with a business idea: “He said, ‘You know, we can own private hospitals,’” Miller later told the New York Times. “To which I responded, ‘You’re kidding.’ He said they had them in California, and it sounded like a good idea.” The roommate started the hospital company American Medicorp, and, by 1972, Miller was the CEO.

A few years later, the company faced a hostile takeover by the health care company Humana. “When you’re faced with a takeover bid, your true nature comes out. It’s war,” Miller, a lover of military history who says his leadership style was inspired by George Washington, told the Times. Humana kept raising the price, and Miller eventually lost the company. But the very next day, he started UHS. His timing was perfect: As deinstitutionalization emptied out state psychiatric hospitals, private facilities stepped into the breach. Between 1983 and 1986, the number of patients in private psychiatric hospitals nearly doubled.

By the ’90s, this freewheeling growth came back to haunt the industry as mounting lawsuits accused psychiatric institutions of defrauding insurers. Medicaid tightened its policies, lowering reimbursements. UHS began buying up floundering facilities. In 2003, the company made the Fortune 500 list for the first time.

A pivotal moment came seven years later, when UHS more than doubled its number of behavioral health beds by buying its direct competitor, Psychiatric Solutions Inc.—even though journalists and government regulators repeatedly had revealed abuse at a number of PSI facilities. In 2008, a Chicago Tribune investigation found that PSI’s Riveredge Hospital, in suburban Chicago, “left sexual predators unguarded,” leading to “savage violence.” The Los Angeles Times and ProPublica found a pattern of abuse and neglect throughout the company’s California establishments. During an earnings call that year, PSI’s co-founder, Joey Jacobs, acknowledged that most of the company’s business came from children and adolescents, “and the vast majority of those are Medicaid or state agency” kids. In a 2009 review, Davidson’s team reported that PSI facilities in five states showed a pattern of violence, sexual assault, poor medical care, inadequate staffing, and “a general failure of professional clinical leadership and accountability.” Nonetheless, in a jubilant call with investors after the acquisition, Miller said, “We know these facilities well, and these are very attractive assets. The fit with our business is outstanding.” (Miller did not respond to a request for comment.)

UHS grew in tandem with a burgeoning population of foster kids. For decades, “troubled” kids had been sent away to military schools and “tough love” programs, but what we think of as the child welfare system emerged in the 1960s and ’70s, as state mandatory reporting laws went into effect and the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act provided federal funding to CPS agencies. Reported cases of child abuse and neglect skyrocketed, from some 60,000 in 1974 to about 3 million in 2000.

Faced with too many foster kids and not enough places to put them, some CPS agencies sent them far away. At its peak in the mid-’90s, Illinois had 800 children placed out of state. After the ACLU sued the state, Davidson was hired in 1994 to ensure the child welfare system was complying with requirements of the resulting consent decree. Over the next 20 years, he and his team crisscrossed the country, visiting and revisiting the facilities, eventually compiling reports on more than 400 of them. Several patterns emerged: Very few kids needed inpatient psychiatric treatment to begin with; the out-of-state treatment centers were substandard; and more often than not, they presented imminent risk of sexual or physical abuse. The researchers found that foster children in the facilities—particularly those out of state—were essentially stranded.

There were a few reasons for this. Behavioral health programs attracted little scrutiny from insurers. “It tends to get, I don’t want to say no attention, but a fairly minimal amount of attention from payers, which I think is generally a good thing,” said UHS’s chief financial officer Steve Filton at a health care conference in 2013. “So, it is a space that tends to operate…under a lot of people’s radar.” Making matters worse, Davidson notes, “these are kids by and large who’ve been taken away from their parents, so they have no family to watch out for them.” Caseworkers didn’t keep a close eye on them either. “In Chicago, they couldn’t even monitor the kids that were five miles away on the South Side,” he adds. “How were they going to monitor a kid in Arizona or Texas? The short answer is they couldn’t and they didn’t.”

Thanks in part to Davidson’s work, UHS attracted the attention of federal regulators, who, by 2013, were investigating 10 of UHS’s psychiatric facilities—including Florida’s River Point Behavioral Health, where they were looking into allegations that staffers had doctored records and diagnosed patients with psychiatric disorders to extend their stays. The DOJ initiated concurrent civil and criminal investigations into false-claims allegations, expanding its criminal probe to include UHS as a corporate entity in 2015.

BuzzFeed then reported that many UHS facilities kept beds filled at the expense of patient safety. Employees in 14 treatment centers were allegedly pressured to hold patients until their insurance coverage ran out—a strategy summed up in the instruction “Don’t leave days on the table.” UHS’s stock dipped; one Oklahoma facility lost state funding and later was forced to close. But the investigations had little effect on the company’s bottom line, and when the Justice Department’s criminal investigation closed in 2019 with no charges filed, share prices soared. The following year, UHS agreed to pay $122 million to resolve allegations brought by the DOJ and state attorneys general. It amounted to roughly one-hundredth of the company’s net revenues that year.

In 2021, after more than four decades at the helm of UHS, Alan Miller passed the reins to his son, Marc—sort of. The 86-year-old executive remains chair of the board, holds the vast majority of shareholders’ general voting power, and controls most board appointments. Forbes estimates his family’s net worth at $1.3 billion—wealth Miller has long used to support conservative politicians, including in his longtime role as a board member of the Republican Jewish Coalition. He and his wife, Jill, live in the Philadelphia area, home of Miller Theater, which hosts touring Broadway shows; the Ronald McDonald House’s Jill and Alan B. Miller Tower; and, in an homage to the benefactor’s military hero, the Alan B. Miller Theater at the Museum of the American Revolution, which houses George Washington’s Revolutionary War tent.

On the flight to Utah, Edwards wore scrubs and handcuffs, accompanied by two security escorts. “I looked like a fucking criminal,” she remembers.

The sprawling Copper Hills campus sits on the outskirts of Salt Lake City, surrounded by a tall fence. Edwards considered her options: She could try to escape again, but she had no money for a return plane ticket. Perhaps she could be homeless in Utah, she thought. “I didn’t care about anything,” she says. “I was thousands of miles away from home. What the hell are they going to do to me?”

When Edwards was admitted in 2015, Copper Hills was spiraling out of control. The previous year, patients “acted out sexually” on a child after staff left them unsupervised, according to court records. State officials put the facility on conditional status, which was lifted in 2016. Physical restraints and sedative injections were used more than a dozen times per day, say two former executives. (I spoke with eight recent employees, including four people in leadership.)

Edwards arrived just before a new CFO named Brian Blohm was hired to help turn things around. Looking back on his tenure, which stretched until 2019, Blohm sees red flags from the beginning. His bonus was based partly on the ratio of employees per occupied bed—with the goal of maximizing the number of beds filled and minimizing the cost of staff. But when crunching numbers, Blohm realized it was impossible for him to be paid his full bonus without running under the state’s staffing requirement. He mentioned it to higher-ups, who eventually changed the bonus plan, though the pressure to cut costs remained. Each week, he was required to send a report on employees per occupied bed to regional and corporate leadership; if there was an increase, there had to be a justification, Blohm explains.

Though state law mandates one staff member for every five patients, a single employee routinely watched more than a dozen kids, former staffers said. A staffing spreadsheet I reviewed from January 2022 shows that, across nine units of patients, only one was within the legal staffing ratio. Six units had just one employee—with as many as 15 children—for hours. Employees lay the blame partly on meager wages: Entry-level “mental health technicians” today begin at $16 an hour—the same starting wage as the McDonald’s down the street.

The understaffing extended to medical personnel: Copper Hills and Benchmark Behavioral Health, another UHS site a half-hour away, house some 200 kids at a time, many with acute psychiatric needs. Yet, for years—until the pandemic hit—they were served by just two psychiatrists, who split their time between the facilities. (UHS said it complies with staffing regulations and doesn’t incentivize unsafe staffing levels.)

Though a clinical team reviewed intake referrals to make sure they could safely meet new patients’ needs, Blohm would often receive calls from UHS executives in other states asking him to free up bed space for a patient at a sister facility who needed to be admitted immediately. “We’d even get calls from our CEO’s boss saying, ‘Take this kid, because they’re in my facility, and we’re not getting paid by insurance anymore,’” said a former Copper Hills clinical director, who asked that Mother Jones not use her name. “The goal was to fill the beds.”

In Harm’s Way

Multiple former Copper Hills employees said that, around 2016, they were informed of a new goal: Increase patients’ length of stay from about seven months to a full year. That way, they could introduce fewer potentially disruptive children while still generating revenue. Rather than leaving a patient’s discharge up to a therapist, the facility implemented a lengthy review process involving its leadership. “There was pressure on me to push back, too, and say, ‘Oh, you think they’re ready?’” said the former clinical director. “‘What makes you say that they’re ready? Have you addressed trauma?’”

Blohm was directed to have his staff report monthly on “unused days,” or times when the facility could have gotten insurance money but didn’t. Minimizing unused days helped determine discharge, he said. A soon-to-be-released patient may be “ready to go home today—and maybe it’s their birthday tomorrow,” he said. “But, you know, we have two weeks approved. We’ll just plan the travel for two weeks." (After four years as CFO, Blohm was fired following a dispute with an employee. He later filed a complaint with Utah's labor division for retaliatory discrimination.)

Long stays were rationalized as better for kids, many of whom had chaotic home lives. Plus, it made life easier for everyone else. “If there is a stable kid on the unit, that is fantastic for the staff and the other patients, who all benefit from having less disruptive behaviors happening around them,” the former clinical director said.

The length of patient stays had come up in UHS investor calls and conferences for years. At the 2013 Credit Suisse Healthcare Conference, Filton, the CFO, noted that nearly all of the reimbursement for behavioral treatment was on a per-diem basis, “and obviously if they spend less days in a facility, then we’re going to be paid less for a single admission.” A few years later, when behavioral facilities started to see a slight downturn in length of stay, Filton assured investors they’d reach out to facilities “to make sure we’re doing all the appropriate...blocking and tackling that we do vis-à-vis length of stay.”

Once more, foster kids offered a convenient patient base. They tended to linger, especially if they had “an uninvested caseworker or a caseworker who doesn’t trust this kid,” said the former Copper Hills clinical director. Chalese Meyer, a former recreational therapist, adds, “They were the kids who stayed there for extended amounts of time, and usually were institutionalized and placed over and over and over again. So they know how to work the system—and they felt comfortable in those places.”

A "personal de-escalation plan" Edwards filled out a few weeks into her first stay at North Star

This, in effect, is what happened to Edwards: Her resistance to Copper Hills morphed into something like acceptance. A few months into her stay, it dawned on her that she wasn’t leaving anytime soon. “So I was like, ‘Might as well start doing what I’m told,’” she remembers. A staffer took her on a walk to the campus store, where kids who had earned enough points based on behavior could buy snacks, and asked for her opinion on what the store should stock. This type of conversation—an adult treating her like an adult—was new to Edwards. “From then on, I was like, I want to be a teacher’s pet,” she said.

She stopped trying to escape and getting into fights. She started doing well in school. She participated in activities reserved for kids who were behaving, like cheerleading and cooking in the campus kitchen. When Edwards talks about Copper Hills, it’s hard to tell if it was genuinely helpful or simply better than before. At one point, she told me, “It was like a high school. It really was. The facility was locked, and that’s it.”

After more than a year in Utah, Edwards was discharged. She returned to Anchorage, where she lived in a group home. But the following months were challenging. Edwards testified in the trial of the man whose abuse sent her to foster care to begin with; he was convicted and sentenced to 39 years in prison. Soon after, she attempted suicide. Edwards says that she did need mental health services during this period, but when she learned that she was being sent to North Star, she was filled with dread. “If I could paint a picture of what North Star is,” she says, “it is literally hell on earth.”

At first, it looked like this North Star stay was going to go like the others. She was unhappy and resistant to treatment. Her psychiatrist expected her to be there a full year. Her three wishes on admission: to get out, to go to school, and to find a foster family.

Then, on the eve of her 17th birthday, it finally happened. A foster family came through. As it turned out, it was someone Edwards already knew—a former North Star staffer. Edwards, thrilled, was discharged early.

By the time she was released in March 2017, she had been in treatment for the better part of five years, including 891 nights at North Star. All told, Alaska’s Medicaid program had paid more than half a million dollars for her care at UHS facilities.

When she got out, she felt like she’d emerged from an alternate universe—one devoid of fashion trends, everyday interactions with strangers, and new technology. “Every time I went in and came out, there was like three new iPhones,” she says. Without the structure of an institutional environment, she had no idea when she should shower or go to bed. Would her foster mom think it was weird if she ate a snack and was hungry again five minutes later? Old reflexes from her treatment life lingered. She found herself asking her foster mom for permission to use the bathroom. Sometimes, Edwards would stand outside her bedroom door, waiting for someone to let her in—only to remember that she didn’t need to wait for a staffer with a key card.

Edwards, like Nathon Pressley, met Jim Davis at a Facing Foster Care in Alaska retreat. Edwards was skeptical of this middle-aged white lawyer giving a presentation with pizza sauce on his chin, but when he talked about suing North Star, she remembers, “I was like, oh no way this man knows about North Star!”

By 2018, Davis was representing Edwards in a lawsuit alleging battery and false imprisonment against North Star and UHS. When Pressley sued OCS, the agency subsequently sued North Star, but in Edwards’ case, the blame-shifting reversed course: North Star turned around and sued OCS. Neither organization, it seems, is prepared to take full responsibility for the children in their care. (The defendants in Edwards’ case have denied the allegations.)

Davis remains just as incredulous about warehousing foster kids at North Star as he was when he first learned about it years ago. “There aren’t any foster homes available, so we’ll just lock them up?” he says. “I mean, we just can’t do that. You can’t take someone’s freedom away because you’re doing a shitty job at recruiting foster families.”

Paris Hilton returned to Utah’s Provo Canyon School on a sunny day in 2020 for the first time since her teenage years. She had the platinum blond hair and big sunglasses of her reality TV days—but wore a T-shirt reading “Survivor” on the back and “Breaking Code Silence” on the front, the name of a campaign to put an end to the troubled teen industry.

“When I was a teenager,” she said to the camera, “I promised myself that one day, I was gonna shut down Provo Canyon School and save all the children.”

The documentary This Is Paris, in which Hilton revealed the abuse she endured over her 11-month stay at the facility, had come out just a few weeks before. Since then, she has proved to be a powerful lobbying force. In 2021, after hearing testimony from Hilton and others, Utah lawmakers passed legislation aimed at increasing oversight, requiring facilities to document instances of physical restraint and seclusion and to allow contact with family members. Hilton testified to state legislatures in Missouri, Montana, and Oregon, all of which have since toughened regulations. Earlier this year, Hilton’s team helped push the Stop Institutional Child Abuse Act, a bipartisan House bill that would increase oversight and data collection of residential programs for kids.

But the progress is halting. Multiple staffers told me that Copper Hills has become more violent since 2020, when Ron Tuinei, the former executive director of Provo Canyon School, took over. Improper restraints from overaggressive employees, some of whom came from Provo Canyon, left children with black eyes and bruises, they said.

Four days after Utah’s governor signed the oversight measure Hilton championed, Idaho CPS sent a 12-year-old named Logan to Provo Canyon School—even though Logan’s aunt, Trisha Leon, who was close with Logan and had no criminal record, wanted to take him in. Despite the new law, Logan’s mother and aunt say they were prohibited from talking to Logan during his first two weeks there. UHS acknowledged in a statement that for “therapeutic reasons, family contact may be limited in the initial admission period to allow patients to adjust and focus on their treatment.” When Logan finally did speak with his aunt, he told her about being slammed against a wall by a staffer. He still had the high-pitched voice of a boy who hadn’t hit puberty. “He pushed me in it really tight, which sort of hurt,” he said. (UHS noted such an incident would’ve been reported to state regulators and law enforcement. In the event of allegations of mistreatment, it said, facilities investigate and take remedial actions.)

Leon contacted everyone she could to get her nephew out: CPS, the governor’s office, local news, and Breaking Code Silence. Hilton made a video for Leon to show Logan. “I just want to let you know that myself and so many others are out here fighting for you and all the other children in that horrible place,” she said in the video. (Hilton told me over email, “He is so young and it was sobering that his stories mirrored my own.” She added, “Provo hasn’t changed and never will.”)

Logan stayed there for more than three months. He now lives with his mom.

Experts note that long-term fixes come down to reducing the need for inpatient psychiatric facilities to begin with. “The rate of institutionalization in what we used to call orphanages has gone down,” says Marcia Lowry, who founded the legal advocacy groups Children’s Rights and A Better Childhood. “But the need to stow kids someplace—to get them basically out of sight and pretend that we’re dealing with their problems—continues to exist.” The statistics are staggering: West Virginia CPS, for example, institutionalizes 71 percent of kids age 12 to 17 in foster care; in New Hampshire, more than 90 percent of older foster youth with a mental health diagnosis are placed in group homes or institutions. Lowry notes that solutions will require more community-based mental health services and support to families to prevent kids from entering the foster system in the first place. To that end, advocates have filed class-action lawsuits on behalf of foster children against state CPS systems.

In some places they’ve succeeded—though it takes time. After Lowry’s team sued New Jersey in 1999, the state’s child welfare system transformed, thanks to two decades of court oversight, pressure from A Better Childhood, and an unflagging court-ordered monitor. Today, the state has among the lowest rates of children in foster care in the country. Only 5 percent of those foster children are in group homes or residential treatment centers—roughly half the national average.

Katrina Edwards ended up spending 891 nights at North Star.

Ash Adams

On a windy spring day, Katrina Edwards and I drove to North Star. She had passed by the facility many times since her return to Anchorage, where she lives in an apartment on the outskirts of town and works at a JCPenney, but this was her first time resting her full attention on its gleaming facade. Edwards’ daughters, both toddlers, sat in the back seat watching The Lorax, oblivious to the tears in her eyes.

“This is...intense,” said Edwards. “This is my childhood in one building. It’s a lot. It’s a lot to take in.”

She later told me she felt awkward on that visit. It was our first in-person meeting. I was a stranger to her, she said, just like the foster parents who’d driven her to North Star. She still struggles to trust people, from grocery clerks offering their help to reporters and lawyers asking about her experiences. “I’m a very friendly person,” she said, “but I hate humans.”

She’s not the only one grappling with the lingering effects of being, as one former foster youth put it, a “treatment kid.” For years, Nathon Pressley, now 26, brought a gun everywhere he went—not because he intended to use it, but because he’d noticed people left him alone when he was carrying. Alexies Ezell, 20, seemed so anxious when I met her at a coffee shop—her voice quivering, her legs crossing and recrossing—that I stopped the interview to make sure she was okay. She explained that social anxiety was a product of treatment facilities. “I used to be really social. I’d come up to people and—just like, strangers—and make friends super easy,” Ezell said. Now, she constantly second- and third-guesses herself, and worries that if she says the wrong thing or expresses any strong emotion, she’ll face consequences.

“The system—we adults—put them in a place like North Star, and literally almost throw away the key,” Davis says. “If you don’t, as a youth, lose faith in the world and all the adults running the world if that kind of thing happens to you, you’d have to be a saint.”

As we visited North Star, Edwards pointed out the familiar spots: the bank across the street; the cement area surrounded by a fence where the kids used to play; the door that she once tried to escape from; the grassy median where a moose gave birth as Edwards and the girls on her unit gaped from inside the facility.

But it was North Star’s wall of mirrored windows her gaze kept returning to, as if she were searching for something. These were the windows she spent countless hours staring out of and banging on in a futile attempt to catch the attention of anyone who might be passing by. “There’s probably a child in there looking at this particular parking lot,” she wondered aloud, “and wishing that she wasn’t in there.”

This article has been updated with additional reporting from medical and public records received since the story published in our September+October 2023 issue.