Cruising south down a two-lane highway in Montana, Braven Glenn looked out onto the open road, the evening sky chilly and dark. It was November 24, 2020—half a year into the pandemic and three months after his 17th birthday. He was a good student, on his way to pick up his girlfriend, a basketball player like him, at her house on the Crow Indian Reservation.

Most days, Braven took his time while driving; his friends sometimes teased him for staying below the speed limit. But lately he hadn’t been feeling like himself—not since his grandma died from Covid weeks earlier. On this particular night, when a car ahead of him sat at around 60 mph in a 70 mph zone, he signaled and passed it, slowing again to the speed limit after crossing back over the dotted yellow line.

Then lights flashed behind him. The car he’d passed belonged to a white cop from the reservation’s brand-new tribal police department. Headquartered inside a former Subway restaurant, the department had launched just five months earlier with Covid relief funding—an attempt by the tribal nation’s chairman to address crime and a huge deficit of federal police.

The officer called dispatch to report a speeding driver, according to law enforcement records, even though Braven wasn’t speeding when she activated her siren.

A chase began.

Within 70 seconds, his car was struck by a train.

More than two years later, on a Sunday evening in May 2023, Braven’s mother, Blossom Old Bull, took a deep breath as she parked her Honda Odyssey on the side of the highway near the site of the wreck. Together we walked through knee-high grass toward the railroad. “This is what’s left of it,” she said, bending over to show me a scrap of burned metal. A suspension spring, a radiator, and a wheel also lay nearby.

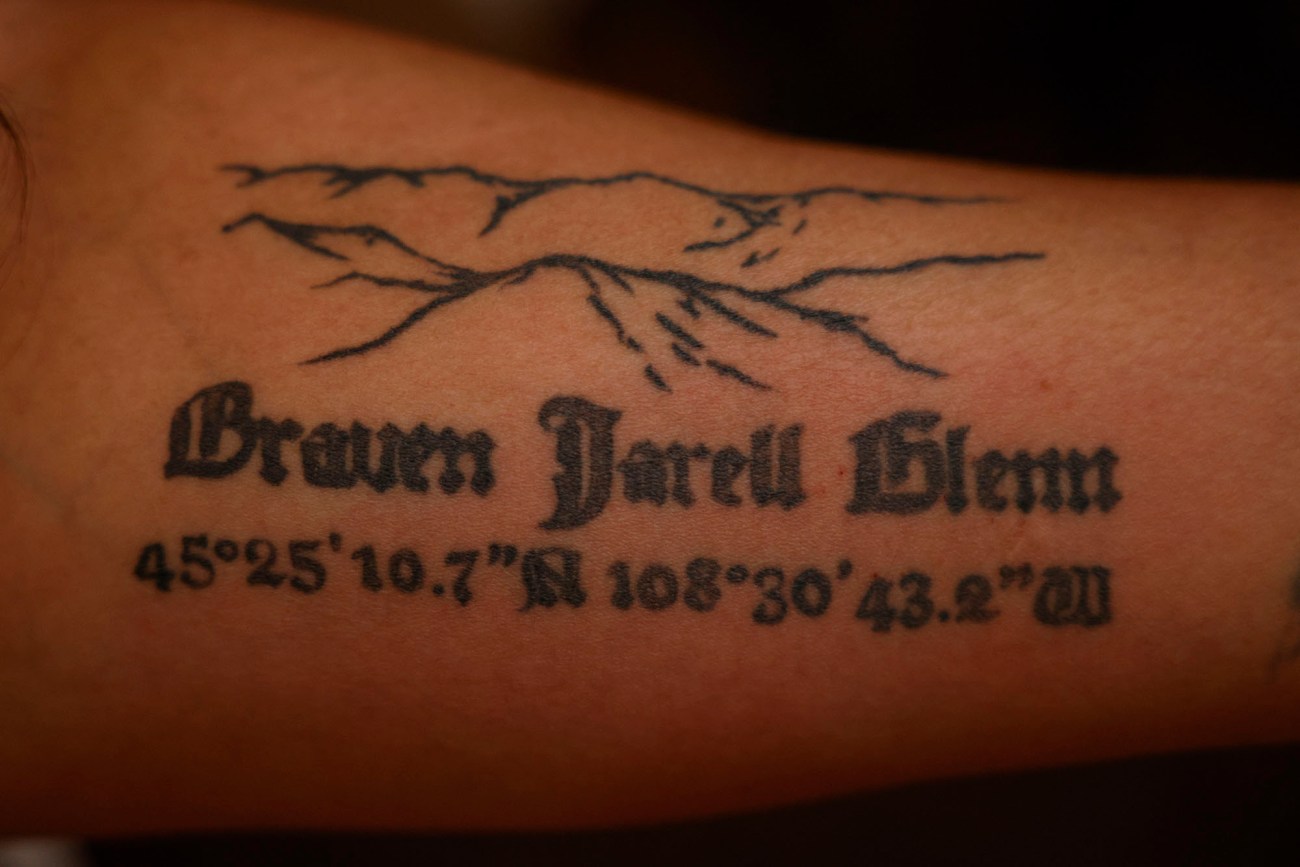

Old Bull tilted up one of the rims to get a better look, exposing a tattoo with Braven’s name on her forearm. She often drove out of her way to make sure the memorial for him was still standing there, a cross with his basketball jersey draped over it.

It had been difficult for her to move forward after the crash; she still had so many questions about what happened. According to interviews, public records requests, and court documents from a lawsuit over Braven’s death, a Crow couple who had pulled over at the wreck site said Braven was denied medical care for a half-hour as he begged for help. The cop who chased him, moonlighting from her job as a Veterans Affairs security officer, left the scene with a crucial piece of evidence: her patrol vehicle. Someone broke into the police headquarters, and the incident report went missing along with records from other cases. Two or three days after the crash, the entire police force disbanded, offering the community—and Braven’s family—no explanation. When Old Bull went to the department for answers, she found a locked door and windows taped over with white paper. “Everybody just up and left,” she recalled.

The disappearance of a new police department so soon after the wreck was highly unusual, the kind of story you might never hear twice. But other parts of Braven’s story were deeply familiar: unanswered questions after deaths on the reservation, inadequate law enforcement. Before 2020, the federal government controlled policing in the Crow Nation—providing only a handful of officers for an area two-thirds the size of Connecticut. Crimes went unsolved, grieving relatives complained of faulty investigations, and some victims wouldn’t even call for help, fearing violence by officers. (Nationally, police kill Native Americans at higher rates than other people of color.) The Crow’s tribal police department was a desperately needed but underfunded counterbalance to a federal system that isn’t working. And Braven was caught up in the dysfunction.

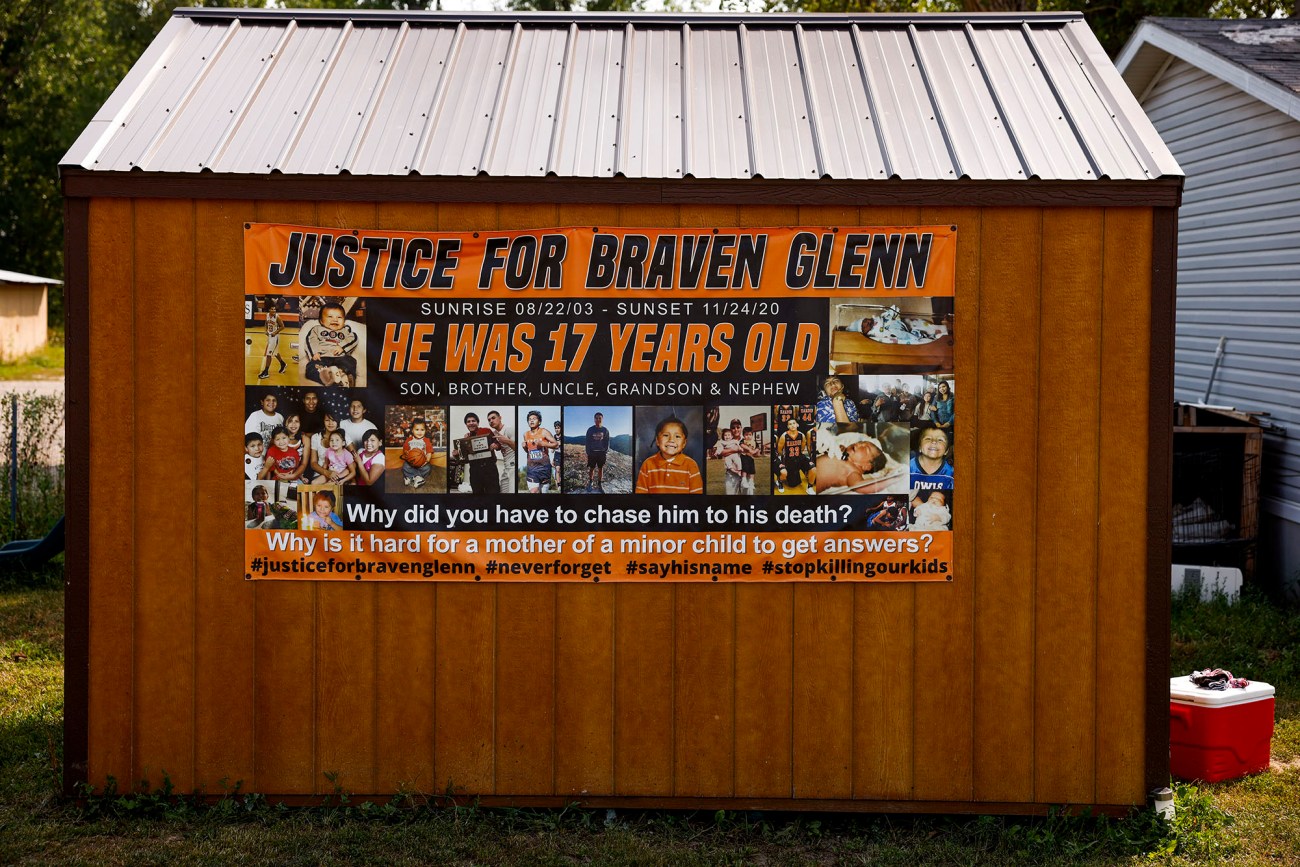

So, too, was Old Bull. After the tribal cops disappeared, it felt like nobody in power would talk to her, like nobody noticed the life that was lost or took responsibility for it. “They come on Native land and they kill, and they just walk away. They think nobody is gonna care,” she said as she drove home from the train tracks, the sun almost set, the clouds a deep blue behind her. “I think they thought that’s how our family was gonna be—that we were gonna let this go.”

“They didn’t expect us to speak out and try to get answers,” she added.

Blossom Old Bull in her home in Crow Agency, Montana

The Crow tribe has about 13,400 members, most of whom live on or around the reservation in southeastern Montana, a lush landscape with towering mountains, open skies, and rivers teeming with trout. The tribal nation earns some revenue from its vast coal and oil reserves. Most people speak Crow as a first language, and the matrilineal clan system remains strong.

Braven and his mom moved to the reservation when he was in eighth grade. Old Bull, a single mom and health care worker from South Dakota, is Lakota, not Crow, and she’d been raising Braven in New Mexico; he was her youngest boy, the eighth of nine siblings. But she wanted him to grow up closer to his father, who was Crow, and some of his older brothers and sisters, and to learn more about that part of his Native heritage. When she’d spent time on the reservation previously, she recalled families camping in teepees for Crow Fair, an annual celebration with a powwow and horse racing and a rodeo, or enjoying the Sun Dance and sweat lodges.

Braven hadn’t wanted to move away from Albuquerque. He was a sensitive kid, and he cried in 2017 when he learned he’d have to leave his basketball team behind. In Montana, the family settled in the town of Crow Agency in a shabby one-story house that they spruced up with fresh paint. It was a rough transition; weeks after they arrived, Braven’s dad died from pneumonia after a struggle with alcoholism. Braven, only 13 years old, stood at his bedside the day they pulled him off life support. I know you weren’t there for me because you were sick, he said, but I still love you. “He was such a good-hearted person, to even think in those terms at that age,” says his sister Marissa.

Braven did his best to settle into the bunkbed room he now shared with his older brother Emilio, who played basketball with him on the corner courts. He grew closer with his half siblings’ grandmother, who adopted him as her own grandson. He loved spending time at her house and would offer to drive her to appointments, help her carry groceries, and put the pots away on the top shelf of her kitchen.

Braven was an honor-roll student who ran cross country and track and played JV basketball.

Though he hadn’t wanted to move to the reservation, it didn’t take long for Braven to hit his stride. His cousin Jayden remembers how quickly Braven made friends: “I left for the summer and came back and everyone knew him. He was really popular.” “He had a goofy personality,” says his girlfriend, Jordan Jefferson. As the years passed, Braven excelled—an honor-roll student who ran cross country and track and played JV basketball, and who was unanimously chosen by his teammates to co-manage the varsity squad, which he hoped to eventually join himself, running miles most days to get in better shape. “He was one of a kind and always ready to take the challenge,” says Mike Beads Don’t Mix, his freshman coach.

But the pandemic marked the start of a shift after Braven’s high school switched to remote learning and he couldn’t see his friends much. In August 2020, the month he was turning 17, his grandma got Covid; she fell into a coma and was unable to sing him “Happy Birthday” like she normally did. Weeks later, she was dead. “He took it really hard” and “got a little more distant from all of us,” his sister JoLee remembers. In his bedroom, Braven played his grandma’s favorite song, “Blue Ain’t Your Color” by Keith Urban, over and over. His grades slipped, and he started drinking more.

The week of Braven’s birthday, Old Bull found him passed out on a couch at his older brother’s house. He lashed out at her after she roused him, and she called the cops, hoping they might teach him a lesson. The police arrested him for disorderly conduct and took him to juvenile detention in Billings, about an hour away.

“My mom, she had to raise all these kids on her own, so I guess you could say she’s tough, but not mean,” Emilio says. “She’s loving, she’d get us a bunch of basketball shoes, but she’s gonna give you the tough love you need to succeed in this world.”

When Braven returned three days later, now on probation, he hugged Old Bull and gave her a letter he’d written apologizing for the incident. “I never want to leave your side again,” he wrote. “I know everybody in our family is disappointed in me…I was crying while writing this letter just because I realized how bad I hurt you.”

He told Old Bull that on his way to detention, an arresting officer from the Crow tribal police “choked [him] out,” according to court records, and that it had scared him, reaffirming all the bad stories he’d heard about law enforcement: His cousin Jayden once watched a cop push his uncle’s head into the concrete, and they both remembered when officers at Crow Fair beat Braven’s 15-year-old cousin Esaias Stops Pretty Places. This is why I didn’t want to call the police, Old Bull told him. “But you need to learn now, Braven, that if somebody needs to call the cops on you,” she added, “this is what will happen.”

Tattoos in memory of her son Braven Glenn adorn Blossom Old Bull’s forearm.

For centuries before the Europeans arrived, the Crow had no police. Instead, warrior groups protected people and enforced laws like the rules of the buffalo hunt. “There’s a big difference between a warrior and a cop,” says Crow historian Alden Big Man Jr., who has studied the tribe’s traditional systems of justice. Warriors’ punishments could be harsh, including things like burning down a person’s home or killing his horses, but if the offender responded favorably, the warriors would compensate his loss, perhaps giving him as many horses as had been taken away.

In the 1800s, the federal government confined the Crow, also known as the Apsáalooke, to the reservation; white settlers often shot at people who tried to leave. The tribe’s nomadic hunters and gatherers were forced to become sedentary farmers and to accept Christianity, learn English, and educate their kids in the colonizers’ way. As railroads brought white ranchers into their grazing areas and banks denied Crows loans, the former warriors were “reduced to begging for handouts during ration days,” according to Big Man, while they “witnessed a complete annihilation of the buffalo, as well as the disappearance of a whole way of life.” In 1887, after a Crow man led a war party off the reservation to steal horses, a colonial agent sent the party to jail. “It was right then and there,” says Big Man, that in the Crow Nation “the system changed from warrior societies to the government enforcing the law.”

Around that time, the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) began appointing Native officers to police reservations—ordering them to prohibit traditional rituals that the colonizers viewed as immoral, ration food and other supplies, and stop any activities that might interfere with white economic pursuits. In 1885, Congress had taken away Native nations’ right to prosecute serious crimes like homicides committed by Native people against other Natives on reservations. (US lawmakers were outraged that a Sioux government in South Dakota had punished a killer according to its own principles of justice—rather than the death penalty, it had fined him $600, eight horses, and a blanket.) Instead, murders and other violent offenses would be investigated by federal agents, some of whom traveled long distances to tribal territories and had little to no long-standing relationship with the people who lived there.

Nearly a century later, as activists from the American Indian Movement protested police brutality and rising crime, Congress passed the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, which created a path for tribes to take back more control of law enforcement. If tribal nations were able to jump through the hoops needed to secure a contract with the BIA, they could divert federal dollars intended for BIA cops to their own tribal police. “It was a real game-changer,” says Lauren van Schilfgaarde, an Indian law scholar who is Cochiti Pueblo and previously directed UCLA’s Tribal Legal Development Clinic. Tribes have since set up more than 200 law enforcement agencies on reservations, far surpassing the number of BIA agencies.

But many tribes were not able to get a contract, including the Crow, and those that have tribal police still lack jurisdiction over major crimes. In 1978, the Supreme Court also removed their ability to prosecute non-Natives, even for most minor crimes. “Even if you have infinite dollars, if your police departments have questionable, shaky, or even no authority over any person within their territorial boundaries, that compromises the entire enterprise,” van Schilfgaarde says.

The federal government, meanwhile, skimped on funding for reservation cops, much as it skimped on health care, education, housing, and rural infrastructure. By 2001, violent crime on reservations was double or triple the national average. “Ultimately, you are of your environment,” Aaron Brien, a historian for the Crow tribe, says in the recent documentary Murder in Big Horn. “When you take an entire society and strip them of any confidence and self-worth they have, it becomes very fragile.” Tribes barely had half the policing resources per capita as non-Native communities: While Baltimore, Detroit, New York City, and DC had between four and seven officers per thousand residents, few tribal departments had ratios of more than two officers per thousand residents. As some communities of color protested overpolicing in cities, says van Schilfgaarde, reservations suffered the opposite extreme, coupled with a lack of resources to address public safety through other means like addiction treatment, employment, and schooling. “It’s incredibly frustrating and dangerous,” she says.

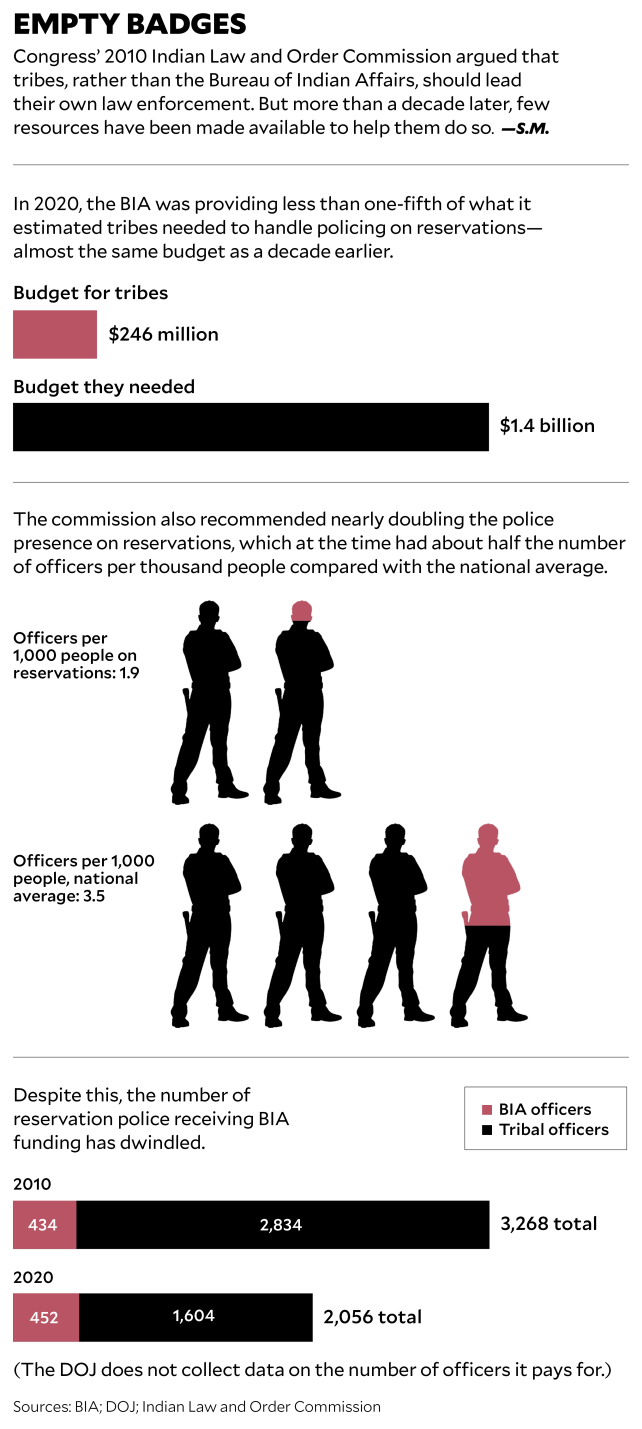

Under the Obama administration, Congress passed the Tribal Law and Order Act, creating a commission to study the problem. The commission, which included Republican and Democratic lawmakers along with Indian law experts, recommended the federal government pay to nearly double the number of reservation police—noting that crime dropped by more than one-third on four reservations that hired extra cops during a pilot program in 2009. The tribes themselves, instead of the BIA, should lead the police, the commission argued; this change would help build trust with the community and more closely reflect tribal priorities and customs. “Public safety in Indian Country can improve dramatically once Native nations and Tribes have greater freedom to build and maintain their own criminal justice systems,” the commission wrote, describing the federal policing system as “a maze of injustice.” The commission set a goal of 2024 to “close the public safety gap” on reservations.

But by 2018, the number of BIA-funded officers on reservations hadn’t grown at all—in fact, it had fallen by about one-third. Carole Goldberg, a commission member appointed by Obama, says Trump’s administration seemed more focused on approving oil pipelines on Native land than on reforming reservation law enforcement. By 2020, the BIA estimated tribes needed $1.4 billion to handle policing nationally but admitted it was only providing $246 million, almost the same budget as a decade earlier. (The Department of Justice provided less than $100 million.) “It’s like working with strings and tin cans at times,” Robert Bryant, chief of police for the Penobscot Nation, had testified to the commission.

During parts of that year, the Crow Nation had just four BIA police to cover an expanse of 3,500 square miles. BIA cops were stretched so thin that “we were pulling 18-hour days” and “going months without a day off,” says Josie Passes, a former officer who wrote a letter to members of Congress begging for backup. A perceived lack of accountability contributed to a climate of fear. “When you start thinking about it,” says Birdie Real Bird, 70, a lifelong Crow resident whose aunt was assaulted during a home break-in and never received a visit from police, “you’re a sitting duck.”

Add to that the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women, an international problem that’s particularly severe in the Crow Nation, where girls are sometimes sex-trafficked and used as drug mules along Interstate 90. Seventy-four people disappeared on the Crow and neighboring Northern Cheyenne reservations in 2019—more than any other area of Montana, which has one of the highest rates of missing Indigenous women nationally. One of them was Braven’s cousin Kaysera Stops Pretty Places, an 18-year-old who loved to sing, dance, run, and wrestle. Five days after she disappeared, the sheriff’s office found her body face down in a fenced backyard, but the office didn’t notify her family for nearly two weeks. Four and a half years later, her cause of death remains undetermined.

Families of the missing often complain about poor transparency and inadequate investigations, and jurisdictional barriers make the situation worse. The BIA can’t arrest people for crimes committed off the reservation, even in border towns like Hardin, where Kaysera died. And on the reservation, other agencies—like the FBI or the sheriff’s office—might have jurisdiction depending on the type of offense and whether the perpetrator was Native. Because it’s often unclear whether a crime took place on or off the reservation and who the perpetrator was, it’s easy for law enforcement to avoid responsibility. When corpses are discovered, investigators regularly write off the deaths as accidental. Commonly, “when our Native women and girls go missing,” says Mary Kathryn Nagle, a Cherokee attorney who assisted Kaysera’s relatives, “law enforcement chooses to do nothing, and it’s up to the family members to do the hard work of investigating.”

By 2019, the Crow reservation was desperate for a change. In August, one of the few BIA cops there—the police chief, no less—quit in protest of his agency’s understaffing. That November, Crow Chairman AJ Not Afraid, the tribe’s chief executive, issued an emergency declaration over the shortage of police.

Days later, he traveled to DC with other Native leaders to discuss the issue with President Trump, whose administration was announcing Operation Lady Justice, an initiative to improve the federal response to tribes’ missing-persons cases. Some Indigenous critics described the effort as uninformed. Trump, for his part, seemed fixated on the Crow chairman’s name. “Is it true—you’re not afraid? Are you not afraid of anything?” Trump asked, laughing.

On New Year’s Day 2020, Not Afraid’s 16-year-old niece, Selena Not Afraid, went missing at a rest stop between Hardin and Billings. A search party, which included Braven, scoured the surrounding fields with ATVs, helicopters, horses, dogs, and drones. Three weeks later, a team from the Interior Department discovered her body less than a mile away. Her death was attributed to hypothermia, but some locals suspected foul play.

Selena’s sister had previously died in a hit-and-run, and her brother was killed by the Billings police. “The Crow Tribe,” Not Afraid had said in his emergency declaration, “will no longer accept ‘lip service’ for the unacceptable lack of law enforcement.” It was long past time, he and his administration believed, to create their own tribal force.

Not Afraid pleaded with the BIA to fund a new police department, according to records of their correspondence. But the BIA kept denying his request, arguing that the tribe, which didn’t have a jail or other necessary infrastructure, hadn’t fulfilled application requirements and couldn’t effectively manage law enforcement.

The pandemic provided Not Afraid with an opening. In May 2020, the Crow Nation received $27 million in coronavirus relief funding through the CARES Act. Suddenly, he didn’t need the BIA’s money; he had enough to launch a police department on his own. Soon he’d hired about 15 officers, tripling the police presence on the reservation. “I was excited about it,” says Yolanda Fraser, Kaysera’s grandmother. “I thought that finally we would have a justice unit that could dig into” missing-persons cases.

However, tribal legal experts say Not Afraid failed to get the necessary approval from tribal lawmakers. “Police departments need to be established by legislation—that wasn’t there,” says Dennis Bear Don’t Walk, the tribe’s former chief judge and now legislative counsel, who says Not Afraid also likely needed lawmakers to sign off on using CARES Act money for policing. Not Afraid declined to comment, but former officials who helped him launch the department told me they believed he had the power to control spending and establish law enforcement during an emergency like the pandemic. (The Treasury Department is reviewing the matter and declined to comment, as did the BIA.)

In Indian Country, tribal chairs have sometimes faced accusations of co-opting police departments for their own purposes—officers can act as enforcers for whoever has the upper hand in tribal management. After the department launched in late June, Not Afraid put out press releases promising to prioritize community involvement and rehabilitation. But he also embraced tactics that appeared to benefit him personally. In August 2020, he responded to an uptick in Covid deaths by imposing a reservation-wide lockdown and curfew, which had public health benefits but also prevented political opponents from campaigning ahead of the November election—even as he held events to drum up support himself.

Some doubted the legitimacy of Not Afraid’s new force. “What if they pull a gun on you: Are they a real cop?” Big Man, the historian, wondered. Gerald “Jay” Harris, the chief prosecutor in Big Horn County, which includes most of the reservation, sent a memo to the sheriff’s department warning that the county could be exposed to lawsuits if it worked with the tribal police, which Harris, who is also Crow, did not view as legitimate. The BIA kept patrolling alongside the new officers but sometimes wouldn’t send calls through to them, according to sources familiar with the tribal force. Passes, the BIA officer, viewed the tribal cops as more of a “militia group than a law enforcement department.”

The federal government had never invested enough resources to create a strong pipeline of trained local police. Shilo Bad Bear was hired as a supervising dispatcher of the new department, even though she only had about 10 months of prior experience. “I was so scared—I didn’t have the proper qualifications,” she says. “I basically had to learn by myself,” adds another dispatcher, who asked for anonymity; she had no prior experience and says she received a sheet of 10 codes but no formal training.

Shilo Bad Bear, a former 911 dispatcher for the Crow tribal police, says she was hired without much experience.

Passes questioned whether the force’s employees had undergone sufficient background checks; she recalled that the BIA had arrested some of them in the past. Some of the cops had retired years ago from other agencies, which meant they were no longer certified, according to one former officer, who also requested anonymity. Others had never worked as a cop. Under Montana law, they could patrol for almost a year before attending a police academy to become certified. It’s a delay that’s common in small rural departments, but one that Michael Gennaco, a consultant in California who specializes in civilian oversight of law enforcement, describes as “a tragedy waiting to happen.” Geoffrey Eastman, a tribal patrol sergeant who did have his certification, later testified in litigation surrounding Braven’s death that “there were no policies in place” to show officers what was expected of them.

And resources were tight. For a police headquarters, Not Afraid’s administration purchased a closed-down Subway restaurant attached to a museum that commemorated the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn. Confused tourists often dropped in looking to order sandwiches, but the counter that once stored cold cuts had become a temporary shelf for officers’ guns. “It felt like a joke,” says Bad Bear. “We were making do with what we had,” says the department’s first police chief, Terrill Bracken, and “building an airplane as we were flying.”

The goal was to create “a department of the people, for the people,” says Bracken, “with tribal members policing their own.” But recruiting Crow cops was challenging because of the long hours, low pay, and limited benefits, and because of the reservation’s extensive clan system; few locals wanted a job that might involve arresting their relatives. So Not Afraid also brought in outsiders, who he hoped would be more impartial.

Bracken himself was a white martial arts instructor from Billings who had briefly worked as a sheriff’s deputy; he moved into a camping trailer outside the tribal police headquarters, away from his wife and two kids, so he could devote more time to the force. “I had so much passion for that project,” he says. “It wasn’t going to get done unless somebody stepped up.” After one month, he was unexpectedly replaced; Crow local Larry Tobacco, who had previously worked for the BIA, became chief.

The new police department also recruited from the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Sheridan, Wyoming, which staffs about a dozen federal cops to patrol a manicured VA campus. “The reservation stays very busy and you would be exposed to a lot more major crime than you are here,” the VA’s police chief told his team in May 2020, according to emails obtained in a Freedom of Information Act request. Under VA ethics guidelines, the agency’s cops generally could not moonlight on the reservation if the tribal police received federal funding. Even though Not Afraid launched the force with CARES Act funds, the tribe assured the VA that no federal funds would be used, according to emails and interviews, so the VA ethics committee gave its blessing. (One former police official told me he was present when an attorney told Not Afraid that the funds became tribal after entering the tribe’s bank accounts; a Treasury Department spokesperson said the funds still would have been federal. Not Afraid did not respond to my request for comment.)

Former tribal police vehicles sit abandoned on the Crow reservation.

Some Crow residents, including Old Bull, questioned whether it made sense to invite outside law enforcement onto the reservation. And these VA officers may not have been prepared for real policing, says Seth Stoughton, a former cop who lectures on policing issues at the University of South Carolina; patrolling a VA medical center, he says, is more like working as a security guard than as a municipal cop. Bracken tells me these officers had previously completed training in operating a police vehicle to get federal certification at the VA. But a VA spokesperson told me its officers receive no training in high-speed chases because they are banned by the agency.

The night Braven died, it was a VA police officer turned tribal cop, Pamela Klier, who chased him.

The Crow tribal police “was a good thought,” says Bad Bear, the dispatcher, but “it seemed like something bad was bound to happen because these guys didn’t know what they were doing.”

The morning before Braven died, he and his brother Emilio played basketball for a couple of hours. Then Braven went to his late grandma’s house in Hardin to see his cousins Jayden and Trey, who were still grieving her death. He seemed fine, remembers Jayden; they “danced each other up,” like they always did to say hello, and then Braven went to fish at a nearby pond.

Around 1 p.m., he texted his girlfriend and offered to pick her up at home after her shift at the Boys & Girls Club that evening. He could borrow the car at his grandma’s house, a black Chevy Malibu, to make the 35-minute ride. It was already dark out when he hit the road, a crisp November night, but it hadn’t snowed yet so it would be an easy drive.

Blossom Old Bull didn’t learn about the crash until several hours afterward. She had just woken up from a nap when she got a phone call. Braven’s older brother Gavin was sobbing. He’d heard that Braven had been in an accident.

“Where is he? Which hospital do I go to?” Old Bull asked frantically.

“He’s dead,” Gavin said, still crying.

Old Bull dropped the phone and screamed. No! she yelled. How do you know?

Emilio hit a shelf in the room he shared with Braven, breaking it. His sister Jolene threw herself on the floor and sobbed. They were all still crying, struggling to comfort each other, when they heard a knock on the door a half-hour later at 10 p.m.

Outside, a tall man with a black shirt and badge stood on the rickety front steps. It was BIA Special Agent Jose Figueroa Jr., who’d just come from the crash site.

A banner demanding justice for Braven hangs outside Old Bull’s home.

I’m sure you guys already know what happened, Figueroa said to Braven’s older brother Keenan outside, according to Old Bull and court records. They clocked him going 90 and chased him, and he ended up going head-on with the train. Figueroa said the family could go to the mortuary the next morning. He asked whether Braven drank or did drugs, then left without offering condolences.

When Braven’s older brother returned inside, he had a confused look on his face. Speed limits often weren’t enforced on the reservation. And Braven was always so slow behind the wheel.

“I didn’t know what to think,” Old Bull says. She was inclined to trust Figueroa, because her dad worked as a cop in South Dakota when she was younger. But Figueroa had hardly given the family any details—not even which agency had pursued her son—and she couldn’t square the story she had been told about Braven speeding with the cautious boy she had raised. The next morning, she grew even more baffled when the mortuary owner said she couldn’t see Braven’s body yet. The owner didn’t tell her that it had already been sent to a crime lab for an autopsy.

Her confusion turned to shock in the days that followed. On the TV news, she learned that it was the tribal police who’d chased Braven, so she drove to their headquarters. But the force had by then disbanded, and the windows of the old Subway were covered in paper. Seething with anger, she tugged on the locked door and pressed her face against the windows, trying to see inside. “There was a life taken, and you just closed everything down without giving the family any answers?” she thought. When she went to the BIA office instead, looking for a police report, an officer handed her a sticky note that simply said “FOIA.” Over the next few months, she got an attorney, Nagle, who’d also been helping Kaysera’s family, and they filed a Freedom of Information Act request for documents with the BIA, but the agency rejected it, citing an ongoing investigation.

The question was, who was investigating? The BIA told Nagle that the FBI had jurisdiction, but an FBI agent told her his office had no case file for Braven. (The FBI, in response to my own FOIA request in 2022, would not confirm or deny whether it possessed documents related to Braven’s death. The BIA told me both agencies initially investigated, but the FBI eventually took control because Klier was non-Native.) When Old Bull tried to get Braven’s death certificate, an assistant at the Big Horn County court couldn’t find it. When she tried to locate his car, the insurance company Progressive said authorities hadn’t released it yet. For weeks, the only information she could access was from Braven’s toxicology report; the coroner personally called to offer his condolences and to tell her that Braven had been drunk and had THC in his system when he died. It would take her four months to get the full autopsy report. She still didn’t know the name of the officer who’d pursued her son or how the chase had unfolded.

Old Bull, a medication aide at a nursing home, is far from naive when it comes to requesting medical documentation. But federal and state law enforcement have a reputation for keeping Native families in the dark after killings. “It’s expected for families not to get information,” says Rae Peppers, a Crow former state lawmaker.

Other families have also struggled to get basic paperwork after their loved ones died. “They never notified me, not once,” Fraser, Kaysera’s grandmother and legal guardian, says of the sheriff’s office that found Kaysera’s body. “It was hard, not getting any support,” says Alvilene Buffalo Bull Tail, whose 14-year-old grandson, nicknamed Jr. Boy, was fatally hit by a train on the Crow reservation in 2017. Authorities deemed his death an accident, surmising that he fell asleep on the tracks; Buffalo Bull Tail suspects someone pushed him, and that law enforcement never properly investigated. “We don’t have closure until at least we know what really happened.”

In Lame Deer, a town on the Northern Cheyenne reservation bordering Crow, Maureen Bryant says her family still hasn’t obtained a death certificate or autopsy report more than two years after her niece DeAnna Limberhand was found hogtied in the Stillwater River. Going to the courthouse for documents felt “like a dead end.” “We kept waiting for paperwork or some kind of information, but we never heard,” she says. “What do you do if no one is helping you?” she adds tearily. “We’re just going through a lot right now, and the not-knowing makes it even worse.”

Rae Peppers, a Crow former state lawmaker, says Native families often struggle to get information from federal and state law enforcement agencies after killings.

The stonewalling led Old Bull and her family to speculate about what happened to Braven, and sometimes they clung to upsetting theories. When they went to the railroad after the crash and observed a second set of tire marks alongside Braven’s leading from the highway through the grass to the railroad, they wondered whether the police ran him into the train. And they wondered if perhaps law enforcement’s lack of transparency was a sign of something more nefarious. “If you did nothing wrong, just release the information,” Old Bull wanted to tell them. “What is it you are trying to hide?”

Her suspicions heightened as witnesses came forward. According to her lawsuit, Maurice and Mavis Mountain Sheep, the couple who’d passed the wreck on their way to get gas, told her they had waited near the railroad for about a half-hour and didn’t see anyone offer Braven first aid. Braven “kept saying, ‘Help me,’” Mavis told the family. But law enforcement “just stood there and stared at him.”

Old Bull also got a text from Bad Bear, the tribal police’s dispatcher. “I had quit by the time that occurred with your son but I can tell you right now, absolutely nothing was in compliance,” Bad Bear wrote. “That place should have not ever been opened…It was a shitshow there.”

For Old Bull, the lack of clarity about the night Braven died was like torture. And she isn’t one to let something like this slide. In February 2023, she tried to sue Klier in federal court for wrongful death, hoping the court proceedings would bring new information to light. She had also sued the BIA, which sent officers to the scene of the crash, accusing the agency of negligently allowing the tribal police to operate without proper training and of failing to offer Braven medical care. “The acts of the agents of Defendant United States shock the conscience and offend the community’s sense of fair play and decency,” her attorney wrote.

Last April, a judge allowed Old Bull’s case to proceed against the BIA, but not against Klier, because Klier had chased Braven in her capacity as a tribal employee, not a federal one. By then, it was too late for Old Bull to sue Klier in tribal court; she’d missed the tribe’s statute of limitations.

Old Bull decided to try a different tactic. In July 2023, she drove to Billings to share her story with a broader audience, including federal officials who were seeking feedback about law enforcement on reservations.

She wasn’t sure what to expect, but she hoped someone in power might finally listen. In the years since Braven died, President Biden had appointed the country’s first Indigenous secretary of the interior, Deb Haaland. Before Haaland left Congress to take the job, she and other Native lawmakers passed a bill to hear testimony about crime and the crisis of missing Indigenous people. Now, Native families were coming from Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota to testify to a federal commission, some driving 20 hours round trip for a chance to speak for 15 minutes.

Grace Bulltail, Kaysera’s aunt, was a member of the commission and encouraged Old Bull to join. But Bulltail felt disappointed at the turnout of elected officials. “We invited the Montana Department of Justice—nobody came,” she says. Not even many Crow tribal leaders showed up. (A DOJ spokesperson said he wasn’t aware of an invitation.)

Still, Old Bull told me afterward that the gathering made her “a little optimistic that something will change.” It helped her feel less alone knowing that her family wasn’t the only one waiting for answers. “Listening to everyone’s stories, you realize you’re a piece of a big, big thing.”

The next month, I was in Crow Agency again, reporting on Braven’s case. It had been nearly three years since Old Bull first started investigating the circumstances surrounding her son’s death, but there’d been a big development since the last time I visited: The BIA had sent me an email with a trove of documents about the incident. It had taken me months of corresponding with the agency—after a year examining the case, interviewing dozens of people, and scouring court and government records—to get the details of her son’s final minutes. I wondered whether my luck with the BIA had something to do with all the time that had passed, or my status as an outsider. Nagle, Old Bull’s attorney, told me journalists are “much more likely” than Indigenous families to get documents from the federal government via the Freedom of Information Act.

At Old Bull’s house, she put on her glasses and joined me on the couch, where I spread out the highlighted pages for her to see.

At first, what Old Bull read in the BIA’s investigative report lined up with what she already knew. It all started on Highway 451 on November 24, she read. But the next detail made her purse her lips: At 5:39 p.m., Braven made a “legal pass” of Klier’s police car over a dotted yellow line, according to the BIA’s description of Klier’s dashcam footage, which doesn’t specify how fast he drove past her. Then, once he got in front of her, he slowed back down to the speed limit, about 70 mph, and Klier turned on her emergency lights to pull him over.

He kept driving.

Maybe he was afraid, Old Bull thought, remembering the officer who had choked him on his way to juvenile hall just months before the crash.

In any case, Braven drove, still close to the speed limit.

Seconds later, he slowed down considerably, and it appeared he might pull over. Klier, now following him at 55 mph, called dispatch and reported that he’d passed her at 90 mph. But Braven did not pull over. Klier activated her siren.

Now, Braven began to accelerate, and she chased him. Seventy-seven miles per hour within half a minute. One hundred and nine miles per hour within a minute. They passed two other cars driving the opposite direction.

Then Braven made a bold move. He turned off his headlights and other exterior lights, a tactic that drivers sometimes use to hide from police. At a bend in the highway, he went onto the grass, driving in the dark toward the railroad.

Old Bull stopped reading and pushed her glasses onto her forehead. “He legally passed her,” she said. “All this kid wanted to do was to go see his girlfriend, that was it. It doesn’t make sense.” She covered her face with her hands and cried.

One-third of all police chases in the United States end with a crash, often causing property damage, injury, or death. Many of these chases begin after an officer observes a traffic infraction, but because of the risks involved, some police departments only allow pursuits after a violent felony or something that puts the public in imminent danger. It’s unclear whether the Crow police had a similar rule. Police Chief Tobacco and Sergeant Eastman testified in the lawsuit over Braven’s death that there was not a handbook of policies and procedures in place, or at least they weren’t aware of one. But the tribe submitted one to the BIA in the months leading up to the crash, according to records I obtained. That handbook states that an officer can only pursue a driver if there’s a “compelling need” and if the chase presents less risk to the public than the driver remaining at large. A “compelling need,” the manual adds, “does not include the mere act of fleeing, even if reckless,” or “traffic and licensing infractions, including DUI.”

Some police officers argue it’s worthwhile to chase after a traffic violation, because maybe the driver is actually fleeing due to a bigger offense, like a dead body or bags of cocaine in the trunk. But suspicion alone, says Stoughton, the South Carolina expert, is not enough. “If you aren’t sure what the benefits of the pursuit are, but you do know the dangers,” including a deadly crash, “clearly the risks should outweigh the benefits,” he says. “Failing to stop for a speeding violation is not a good reason to kill someone.” And that’s especially true if the driver may be intoxicated, he says. In Braven’s case, “what’s more dangerous—him driving the speed limit while drunk,” or him being chased and “driving 100 mph while drunk?” says Stoughton, adding that Klier could have arrested him later: According to court documents, she’d already noted his license plate number. “Had she terminated the pursuit,” policing expert Susan Peters testified in Old Bull’s lawsuit, “more likely than not, Braven J. Glenn would not have been involved in a vehicular fatality accident.”

Scraps of burned metal, including a suspension spring, a radiator, and a wheel, are what’s left of Braven’s car near the site of the crash.

As Old Bull and I read over the BIA reports, it became more and more apparent that the investigation into the crash had been flawed from the start.

Moments after the crash, Klier called dispatch. “Send medical,” she said, according to call logs. “He just got hit.” Soon, other law enforcement arrived—from the tribal police, the BIA, the state highway patrol, the sheriff’s office, and the fire department. But according to other records from the investigation, they struggled to get on the same page, a common complaint on reservations. Bodycam footage from Deputy Sheriff Michael Colvin, a county cop who was assigned to divert traffic, offers a small glimpse into the confusion.

“Hey, where’s the body at?” an officer asked Colvin.

“I don’t know,” Colvin said. “Tribal PD was first on scene, and they told BIA where it was at…He said it wrecked some place down here.”

“Was it crossing or what?”

“I don’t know. That’s what I asked, but he didn’t really give me an answer.”

Seconds later, paramedics drove past Colvin, lights flashing. A voice came over his radio: “They’re on scene, but they’ve been canceled.” The paramedics left.

Six minutes later, a tribal police officer called dispatch, according to records I obtained from the county attorney’s office. “Tribal asked why EMS canceled,” the dispatcher noted in a call log, “because they didn’t make the determination the individual(s) were deceased.” The tribal officer asked the paramedics to return. Later, Braven’s girlfriend, Jordan, who drove over after Braven didn’t pick her up after work, saw men loading a body bag into a white truck.

Meanwhile, BIA special agent Figueroa arrived. According to an investigative report, he told Klier that the BIA would investigate the crash. Later, he told another tribal officer on the scene that Klier would need to have her blood drawn and that he needed the dashcam footage from her patrol vehicle. The officer acknowledged his request, but when Figueroa returned from speaking with the train conductor, Klier was gone and had taken the police car with her. The tribal officer had given Klier permission to go home, according to the report; she’d been visibly shaken up after the crash.

“It’s like, what the fuck?” says attorney Tim Bechtold, who is representing Old Bull in her lawsuit. “All these cops not knowing what the fuck to do.” Klier’s decision to take her vehicle was “incredibly unusual and wildly inappropriate,” says Stoughton, the police expert in South Carolina. “It’s not that much different from an officer who’s involved with a shooting taking their gun home instead of turning that over for evidence.”

A former tribal police officer, who requested anonymity, later told me he saw Klier at the police station soon after the crash. The officer drove to the railroad and alerted Figueroa that the car might be at headquarters. “You need to go down there and get that vehicle now,” he recalls telling Figueroa. But it’s unclear if Figueroa went; he didn’t locate the car that night.

The next day, Figueroa told the Crow police department that he would need a copy of Klier’s incident report and the dashcam footage. The following day was Thanksgiving. And a day after that, Figueroa learned the police department had already “disbanded and closed shop,” according to the BIA investigation. “No one knows who has access to their reports.”

Then things got even more complicated. In mid-December, when Figueroa reminded the tribe that he still needed the report, he learned that someone had broken into the former police headquarters. Now the records he needed were missing.

Figueroa still didn’t know where Klier’s police car was, either. So in January, he drove to Wyoming, where she lived and worked with the VA, to find her. She said she was waiting for an attorney and didn’t want to talk. (She also declined my request for comment.)

Figueroa drove back to Montana and reached out to the tribe’s homeland security director, who said he was “unsure where anything was,” this time citing two break-ins at the police headquarters, but that he would try his best to find the records. (Police equipment, including guns, had also gone missing.) Two weeks later, in February, Figueroa learned the headquarters had suffered four break-ins, but someone had finally located Klier’s police car; Figueroa copied the dashcam footage. In May, he obtained the BIA’s dispatch logs, but the tribal police’s logs concerning Braven’s death—and Klier’s incident report for it—were still missing. (They don’t appear to have ever been recovered.)

Harris, the former Big Horn county attorney, whose term ended in late 2022, believes the US government may be responsible, at least in part, for mistakes made by law enforcement that night. In addition to allegedly failing to provide potentially lifesaving medical care, the BIA did not properly secure the scene of the crash and allowed Klier’s police car to get away, and then took months to find it. “You would think [the BIA] would have their hair on fire chasing everybody down,” says Jonathan Smith, who oversaw investigations into police department misconduct at Obama’s Justice Department. If it took that long to locate the car, he adds, “it seems unlikely they tried as hard as they could.”

Old Bull’s lawsuit is scheduled for trial this summer. The US government denies any wrongdoing. Since the BIA did not employ the Crow’s tribal police force, an attorney for the government wrote in response to the complaint, “the United States cannot be held liable…for their negligence.”

After reading the BIA reports, Old Bull retraced the new information. “There’s so much they did wrong…It’s like a ton of bricks just hits you,” she told me, motioning with her hands toward her chest. She wondered whether things might have been different if she’d gotten some of this information sooner—whether it would have helped her legal case, or at the very least helped her heal.

And it stung, she added, knowing that an outsider like me—a white journalist with no connection to Braven—could access all these FOIA records, while she, Braven’s mother, had been denied. It took suing for her to begin getting evidence, and even that, she said, didn’t include some of the key details I’d just shared with her. “I fought so hard to get that, years and years,” she said. “It’s like we don’t matter, like we are nothing.”

Two days later, former tribal police chief Terrill Bracken arrived at my Airbnb in Billings. I’d told him that Old Bull was interested in seeing him. Bracken wasn’t leading the police department when Braven died, and he knew little about the chase. But if Old Bull wanted to talk, meeting her seemed like the Christian thing to do, he said. “Anything I can do to help her with the grief that she is going through, that’s why I’m here,” he told me.

Old Bull, who’d worked a 12-hour shift at the nursing home that day, sat in her car outside the house for a moment before entering. For months, she’d been asking God to help her forgive, but it was hard to let go of all the resentments she carried. Maybe, she thought, it would be easier after talking with Bracken and hearing another perspective. “I have to come face-to-face with somebody that started this whole thing, and just get some straightforward answers,” she told me at the front door.

After taking a seat opposite the former police chief, Old Bull anxiously tapped on her glass of water with her fingers, tears welling in her eyes. Bracken said he was sorry for her loss. She thanked him. “That’s our right to know what happened to our child,” she said. “And I never got that. I had to fight and fight and fight.”

“And it should not have to be that way,” Bracken agreed.

“It’s frustrating for me,” he added, “because I know what we were working toward was going to be so much better,” he said of the tribal police.

Their conversation stretched on for two hours. At points, Old Bull seemed to soften toward Bracken. “I do feel better with you talking to me. I can see you now as a person,” she said.

But when he began talking about Officer Klier, the mood shifted. “For all we know,” Bracken said of Klier, “she’s not doing very well right now.”

“She’s not the one hurting,” Old Bull said quietly.

“I’m not saying who’s suffering more. It’s not a contest,” Bracken responded. “But I’m just being honest with you: Given the information that I have, I can’t see how I would have acted any differently than the officer. And that’s a difficult part of the job.”

Old Bull sighed. “I gotta work in the morning,” she said, signaling her intent to leave.

“Would it be okay if I prayed with you?” he asked.

She nodded, her eyes shut, and began crying after he placed his hands over hers.

Driving home, Old Bull was glad to have spoken with Bracken. But as she lay in bed the next morning, recalling the conversation, her anger grew. “For him to say, ‘Oh, poor Pamela, I wonder what she’s going through’? How dare you,” she thought.

She picked up her phone and texted me: “Samantha there was a lot that bothered me. He put her on this pedestal,” she wrote. “To sit there and emphasize her feelings, when this is about the loss of my son and her actions made that loss happen. I feel like it was an attempt…to glorify what she did as a cop.”

“This is a system made to oppress us. It’s been this way since Columbus,” she added, before putting down her phone and heading to work.

The doors of the tribal police headquarters were locked the first time I visited last year, but I could peek inside to see how abruptly it was all abandoned. The police’s whiteboard calendar still showed the Thanksgiving party scheduled for the day Braven died. Stacks of unused call logs sat in dusty boxes. In the parking lot, a makeshift jail remained, two tiny cells inside a shipping container. The refrigerated counter that once held Subway’s sandwich ingredients—and then guns—had been removed. The dining tables that the cops used as desks were piled outside beneath cottonwood trees.

The temporary holding cell in a modified shipping container outside the former tribal police station

The former tribal police station in a closed-down Subway store on the Crow reservation

There was never a public explanation for why the department closed in late November 2020, leading to speculation. Old Bull still wonders whether the police are hiding something. Big Man, the historian, wonders if they packed up and left because of poor training and lack of community support, and because Braven’s chase was “the final straw.”

“There were a lot of reasons why it shut down,” says one of the tribal police officers who requested anonymity. “It was starting to fail” even before Braven’s accident, and then “the money stopped coming in.”

Bracken doubts Braven’s death was the only motivation for disbanding, if it was a motivation at all. He blames politics: A few weeks before the crash, Chairman Not Afraid lost the election to Frank White Clay, a former tribal lawmaker who believed propping up a new police force with Covid relief funding violated federal spending guidelines. “We’re still trying to figure out exactly where that money went,” White Clay would later tell a journalism student at the University of Montana in 2021. He agreed the reservation needed more law enforcement but said this police force was just “playing cops.”

Rather than give White Clay the satisfaction of disbanding the force, Not Afraid beat him to it and shut down the department about a week before the inauguration, according to another former tribal police official. It was possible Braven’s accident may have been “the catalyst, the icing on the cake,” but it wasn’t the primary reason for closing, he said.

Harris, the former Big Horn county attorney, says the department’s sudden closure was evidence that it was never properly established. “A legitimate, lawful police agency doesn’t just end because a chairman or president or governor says, ‘All right. Enough,’” he tells me. “This [police department] was a mirage, a facade.” It was “a temporary fix, nothing more than a Band-Aid,” one of the former police officers tells me.

“Did we do everything perfectly? Absolutely not,” says Bracken. “But were we doing the best we could with what we had? Yes. I really believe that department would have flourished into something had it gotten a fair opportunity.”

The Crow police force’s brief existence and abrupt end is not just a story about a tribal administration’s mistakes, says Big Man. It is also a story about the federal government’s repeated failures leading up to 2020—to keep families informed, to conduct thorough investigations, to keep the reservation safe. And it shows “a real need for clear, meaningful communication” with Crow people, says Kristina Lucero, who directs the American Indian Governance and Policy Institute at the University of Montana, “about expected goals and the mission of what law enforcement should be doing.”

Many of the families who testified with Old Bull in Billings were adamant that they want more transparent policing, including easier access to information after loved ones die or go missing. “Authorities at all levels must improve communications with family members, who are too often left in the dark for days, weeks, or months,” causing “enormous stress,” the federal commission wrote afterward.

Indigenous communities also want more funding: In 2022, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe in Montana sued the US government because of a shortage of police. The state’s Fort Belknap Indian Community sued too, after the BIA refused to provide more public safety money. “What’s happening at Crow, that’s pretty extreme,” says UCLA’s van Schilfgaarde, but “when budgets are tight, these [police] departments come and go in a way that would just never happen in other communities.” The problem isn’t just in Montana, she adds. Most Native villages in Alaska have no law enforcement presence whatsoever.

Two days after his inauguration in 2020, White Clay informed the BIA that “an independent law enforcement effort is not the direction that the new administration of the Crow Tribe intends to continue.” Since then, complaints about BIA policing persist. In July 2021, the tribe sued a BIA officer after he was caught on video failing to stop his dog from biting someone handcuffed after a traffic stop, for nearly a minute, leading to three surgeries on the man’s ankle and foot. “Unfortunately, nothing in this video is surprising to anyone who has lived on the Crow Nation,” the tribe’s attorney wrote. “I had a lot of faith in the police before,” Old Bull says, “but after Braven died, I don’t believe they’re there to protect us.”

In December, President Biden signed an executive order to remove red tape that has hampered Native access to law enforcement funding. But legal action might be more effective. In May, a US district judge encouraged the feds to meet with the Oglala Sioux Tribe in South Dakota and “figure out how to more fairly fund” tribal policing—or else go to trial. The decision was “the first to acknowledge that the government owes a treaty-based duty to fund law enforcement for [an] Indian tribe,” according to the Oglala Sioux’s attorneys. And they say it could at last force a legal reckoning over Washington’s centuries-long harm to Native justice systems.

A successful reckoning must give tribes more jurisdiction and make room for them to reimagine policing and public safety in ways that reflect their own cultures and customs, says Goldberg, the Obama appointee to the Indian Law and Order Commission. She’s seen Indigenous communities that involve spiritual leaders in justice proceedings to weigh in on punishments and design a path forward. The Tulalip reservation in Washington state, in keeping with its values, has required police to stop by the Boys & Girls Club twice a shift to help kids with homework, and they attend elders’ breakfasts to share data and answer questions.

On the Crow reservation, most people I asked said the tribe needed more law enforcement, but they also emphasized the importance of better officer training. Some said they wanted to think about public safety in a more balanced way, with funding for mental health, addiction treatment, housing, and education. Investments like these could make it easier to recruit good local cops, says the University of Montana’s Lucero, since people might be less hesitant to police their relatives if the justice system offered more second chances and paths toward healing. “You just can’t arrest people, lock them up, and expect to throw them back in the same situation and change,” says Big Man. “Past traumas have created who we are,” adds Old Bull. “Get people into treatment and get them help and programs before moving in a police department.”

Tribal nations that are successful with law enforcement, says Goldberg, are ones with “strong congruence between the views of the community and the way it’s done.”

Braven’s family built a memorial for him near the site of his death.

Old Bull buried Braven about an hour from home, at the foot of the Pryor Mountains, next to the graves of his father and his cousin Kaysera. The cemetery is small and quiet, off a dirt path surrounded by fields, and most of the gravestones are simple, some with fake flowers and crosses. Old Bull and her family go there often to mow the grass around Braven’s plot and decorate it with gifts, like chocolate-covered pretzels, one of his favorite snacks, and a basketball covered in their handwritten messages for him.

At times they’ll play music and reminisce about the ways he made them laugh, like how he’d make a muscle like Popeye and kiss it. When two of his older sisters got pregnant, they went to the cemetery and told him about it. When his younger sister graduated high school, she wore a cap beaded with the words, “We did it Brave.” They feel sometimes like he’s still with them, even sending them messages. The night before his funeral, when Old Bull slept in a teepee with his remains, in keeping with her Lakota traditions, she and another family member heard a basketball bouncing in the middle of the night, even though everyone else had long since gone to bed.

In August 2023, on what would have been his 20th birthday, Old Bull and her kids drive to the cemetery to visit Braven. They eat chocolate cupcakes with sprinkles, Braven’s favorite, and release balloons into the sky for him.

“I want them to know he was a person too,” Emilio says. “He was a good kid and had big dreams, and for them to hide in the shadows—he deserves justice, the truth.”

“Accountability and closure—that’s what my mom really needs, what I really need,” adds sister Marissa.

“I do want accountability, and I want them to admit this didn’t have to happen,” says Old Bull.

On the drive home around 10 p.m., Old Bull sees a white owl sitting on the side of the road. In her tradition, owls are harbingers of death. The last time she encountered one, her mom died, and not too long afterward Braven did, too. When she arrives home it’s almost midnight, and she lights a bundle of sage and cedar, calling her kids and grandkids out of the house to smudge them and help keep them safe. “Bring the babies out,” she instructs, walking to each person with the bundle and watching as they wave the smoke over their heads and into their hearts, all the way down to their legs. “Who’s next?”

This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.

Old Bull visits the memorial placed where Braven died.