along the coastal 101 in brilliant blue, the bright May sky beginning to soften toward sunset. Chin Rodger felt a lift of optimism as she exited the freeway and arrived at a sushi restaurant tucked away in the tony town of Montecito, where she greeted her 22-year-old son, Elliot. He looked well. He wore a designer shirt and Armani sunglasses, his dark hair styled, a smile on his boyish face. He was happy to see her and his younger sister, Georgia, a high school senior who often joined their mom for the drive up from Los Angeles.

This was a favorite dinner spot for their monthly get-together since Elliot began attending Santa Barbara City College more than two years earlier. They ordered their usual plates to share and chatted about nothing in particular. Seated across from Chin, Elliot began glancing over her shoulder.

“Look at that couple,” he said, eyeing a young man and woman at another table. He muttered that the guy looked unworthy of his attractive blonde date. Chin was used to his awkward social insecurity, part of his longtime emotional struggles, and she steered him back to positive conversation. She was pleased when the always skinny Elliot ordered an additional roll and began polishing it off.

“Wow, you’re eating a lot,” Georgia said.

He shrugged. “So what?”

Elliot liked this place because it felt far removed from where he lived in nearby Isla Vista, a small bluff-top town hugging University of California, Santa Barbara, whose party scene once attracted Elliot but had become alienating for him. Chin watched him enjoying the meal. It had been about three weeks since he had dropped out of communication for a few days and she found a video he’d posted online about his frustrations over girls. Worried, she’d called a social worker Elliot met with when visiting home, who said they should dial a crisis hotline in Santa Barbara. When police went to Elliot’s apartment for a welfare check, they concluded that all seemed fine with him, and his texts and calls with Chin since then had been encouraging. He’d told her his spring classes were finishing well and talked of promptly paying off a parking ticket, which struck her as part of his emerging self-improvement.

Chin cut the visit a little short because Georgia had plans with friends later that night. Their usual stroll for coffee and dessert would have to wait for next time. They hugged Elliot goodbye in the mild evening air, then got on the road back to LA.

Chin left heartened by her son’s relaxed demeanor and newfound appetite. It would be years before she would begin to learn what those really were: the last in an accumulating trail of warning signs.

The following week, Chin was driving home from work on the Friday of Memorial Day weekend when she got the news that the hot tub at her employer’s estate was malfunctioning. In recent years she had settled into her job as a trusted personal assistant to a family of wealthy philanthropists, while continuing to raise the two kids jointly with her ex-husband, Peter Rodger, a photographer and filmmaker. She pulled over from LA traffic and made a call to line up a quick repair. The forgettable task would soon be seared into her memory as a last bit of normalcy.

When she got home, Georgia was headed out for an overnight with friends, and Chin decided to relax with a bath. A little after 10 p.m., she saw a text message from Gavin Linderman, the social worker helping Elliot. Linderman was one of several young counselors in LA and Santa Barbara enlisted by Chin to give Elliot life-coaching, augmenting the therapy he sometimes did with a psychologist. Chin had texted with Elliot that evening to celebrate the end of his semester, and she figured she’d catch up to Linderman’s message later. Then he called.

“Have you checked your email?” he asked, his voice taut.

“No,” she said, “I just got out of the bath.”

“There’s an email from Elliot.”

An hour before, her son had sent out a 137-page document to nearly three dozen people with a terse message: “Attached is Elliot Rodger’s life story, which explains how I came to be the way I am.” Titled “My Twisted World,” much of it was an extended tirade about his feelings of extreme social isolation and lack of sexual experience, for which he categorically blamed women. He vowed “a day of retribution” and at the end described a plan to commit mass murder. Linderman had also found a seven-minute video that Elliot had just posted on YouTube in which he declared the same intent.

Chin glanced at the materials and quickly tried calling Elliot, but there was no answer. She dialed 911, got connected to the Santa Barbara police, and said she urgently needed to locate her son. She was disoriented: Elliot had messaged with her amicably about three hours earlier, and she had yet to really grasp what the long document and video revealed. She called Peter, who was having dinner at home with his wife and another couple. They set out immediately for Isla Vista.

As Chin left her home in West Hills and drove up the 101 freeway, she called the manager of Elliot’s apartment building and pleaded with him to go knock on Elliot’s door. He told her there was chaos in the area from a shooting and car chase, and that he thought it best to wait until morning. Chin knew Elliot liked to cruise around in the black BMW she’d gotten him—was he somehow involved or hurt? As she pressed on toward the coast, she received a call from Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Detective Joe Schmidt, who asked her a few plain questions, including whether Elliot had firearms. That startled her: Elliot had never shown any interest in guns. She explained that he had social problems and saw a therapist, and that she’d been unable to get him to call her back that day. The detective asked Chin to meet him in the parking lot of a Home Depot near Isla Vista, where Peter also was headed, accompanied by his wife and their dinner companions.

The hour-plus drive felt like forever. Chin reached the meetup location and found Peter and the others, and they waited in the lot anxiously. Around 1 a.m., a police vehicle pulled in. Schmidt walked over with a fellow detective and asked to speak with Chin and Peter privately.

“Where is my son?” Chin implored. “I’m not answering more questions until you tell me where my son is.”

Schmidt conferred for a moment with his colleague. Authorities were still in the early stages of piecing together a string of violent events in Isla Vista. He informed Chin and Peter that police had found a driver’s license on Elliot’s person at the site of a car crash, and that Elliot was deceased.

Chin dropped to her knees. She heard a guttural sound rising from Peter. Beneath her was hard ground, but she felt like she was plummeting.

They would soon learn that the news was far worse. Elliot had perpetrated a horrific massacre, one that still stands apart in America’s epidemic of mass shootings. The case would be documented extensively by investigators and play a unique role: Its unusual range of evidence would show experts more about what leads to such attacks and help advance a growing field of violence prevention. And eventually, Chin herself would join that effort.

Peter Rodger and Chin Rodger the day after the shooting

Splash News

Before the sun went down on May 23, 2014, Elliot Rodger ambushed three college students inside his rental apartment in central Isla Vista, stabbing them to death with fixed-blade hunting knives. Two of the victims were his roommates: Weihan Wang and Cheng Hong, both age 20 and students at UCSB. He killed Wang first, in Wang’s bedroom, according to an investigative report from the sheriff’s office. Hong, later returning from class, died second. The third victim, 19-year-old George Chen, a friend of Wang’s who lived on the UCSB campus, had come over after that, around dinnertime. Elliot’s violence escalated with each victim, stabbing them 15, 25, and 94 times. He covered the first body, and then the second, with blankets and clothing, likely to preserve his element of surprise.

He had a history of conflict with his roommates, who had been assigned by building management, a common practice locally with student renters. Four months earlier, Elliot had called the police claiming that Hong stole candles from his bedroom, and then had pressed the building manager in an email to kick out Hong over this “extreme problem.” The 137-page screed he blasted out the night of the rampage described his intent to lure victims to the apartment and make it his “personal torture and killing chamber,” which would require first killing his roommates. According to investigators, crime scene evidence suggested he’d rehearsed by stabbing pillows and slashing at the sheets on his bed.

Though the small apartment was within earshot of others, no one in the two-story complex noticed anything was wrong. Elliot’s roommates often shouted with excitement while playing video games together in the apartment—he’d complained bitterly about that too—and raucous noise was common in a college town. Or maybe the lack of notice was explained by the search history investigators found on Elliot’s laptop: “Quick silent kill with a knife.”

By the end of the day he’d used towels to wipe blood from the walls, removed his bloody jeans and shirt, and showered and put on fresh clothes. Around 7:30 p.m., he went to the Isla Vista Starbucks a few blocks away, where he ordered a triple vanilla latte and texted with his mom. Chin had asked Elliot earlier in the day to call when he was finished with his classes.

“I’ll call you tomorrow when I’m in my car,” he now messaged back. She replied asking why he couldn’t call sooner.

“Feel like relaxing right now,” he said. “Maybe later tonight then. All done with school now.”

“Congrats,” she said.

“Thanks.”

Latte in hand, he walked casually out of the Starbucks and returned to the apartment, where he wrote in a diary he’d been keeping for more than three years. Unlike the other neatly scripted entries, the jagged handwriting spilled down the paper: “This is it. In one hour I will have my revenge on this cruel world. I HATE YOU ALLLL! DIE.”

Just after 9 p.m., fueled by caffeine and Xanax, he sent out his screed, posted the video to YouTube, then drove his car a few blocks and parked. Recently he’d been surveilling what he called “the hottest sorority of UCSB.” This time he brought three semiautomatic pistols and more than 500 rounds of ammunition. He walked up to the front door, wearing extra ammunition strapped to his waist and carrying a filled gas can. He tried the handle, then poked at the keypad, guessing at the entry code. Then he started banging repeatedly on the door. In a fortunate twist of fate, about 40 of the residents were away on a trip to Las Vegas, and the remaining handful felt wary enough not to answer.

He left the gas can at the door, went back to his car, and spotted three sorority members walking down the street. He rolled up on them from behind with the passenger-side window down and opened fire. The burst of bullets gravely injured 20-year-old Bianca de Kock and fatally wounded her friends Katherine Cooper, 22, and Veronika Weiss, 19. Calls to 911 began to flood the system as he drove a few blocks to the front of a deli mart and fired at people who fled inside, killing 20-year-old Christopher Martinez with a single shot from close range. Then he headed for the nearby oceanfront neighborhood, ramming people and firing more shots on his way to the party epicenter of Del Playa Drive. He plowed into some victims with enough force to shatter his windshield and catapult them to the pavement.

Cruiser lights and sirens pierced the Isla Vista night as police pursued the black BMW, twice exchanging gunfire with Elliot along Del Playa and the surrounding blocks. On the passenger side of the car were the other pistols he’d purchased at area gun shops over the past 18 months, the extras to ensure he could finish his plan even if one jammed. About eight minutes into the rampage, with a bullet graze to his left hip, he circled back onto Del Playa for another pass. As police closed in, he followed a script common among mass shooters: He raised his Sig Sauer 9 mm to his head and pulled the trigger one last time. Witnesses heard the final shot and watched as the BMW, still moving westbound on Del Playa, swerved to the right and smashed into a parked car.

By then Elliot had murdered six people, wounded and injured 14 others, and traumatized countless more. Where the attack ended was no coincidence.

Elliot at Starbucks, with his mass murder already underway Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office

Elliot’s black BMW at the crash site on Del Playa Drive

Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty

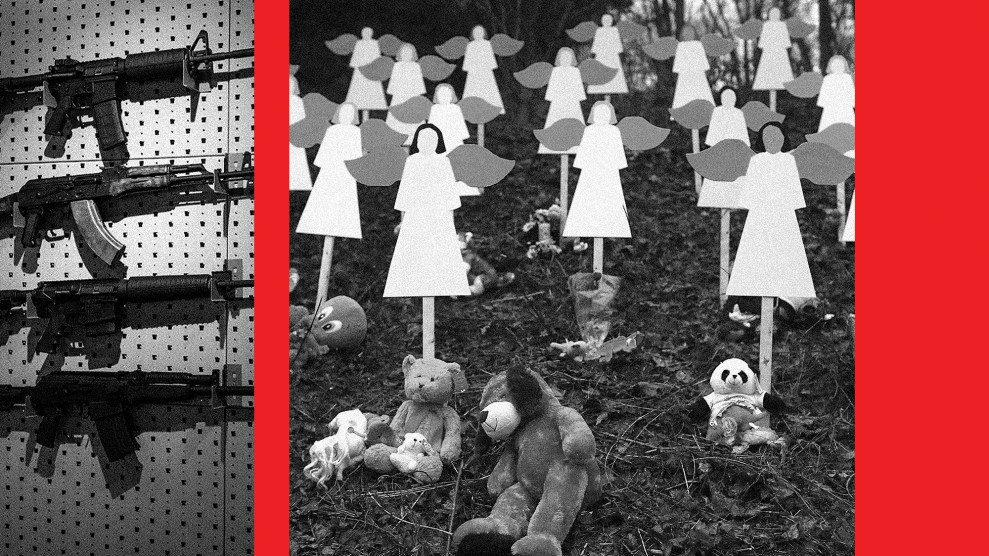

but exhuming Elliot Rodger’s life and ghastly final actions remains fraught. It risks inflicting further pain for the victims’ families and other survivors, and new revelations could feed the kind of infamy many perpetrators seek. The case stands out among the hundreds I’ve studied in 12 years of reporting on mass shootings. To this day it fuels copycat attackers who fixate on misogyny, making it an ongoing subject of news coverage and various academic and security research. It also helped catalyze policy change, in particular the spread of “red flag” laws aimed at keeping guns away from unstable people.

Yet from the start, this tragedy has been wrongly mythologized in the media and academia and poorly understood by the public, its lessons for prevention buried. The voluminous case evidence casts light on warning signs, the complicated role of mental illness, and other keys to effective intervention. Elliot’s behaviors leading up to the attack also make clear how the common portrayal of mass shooters is misguided and undermines the potential to stop them: They are not inscrutable monsters who suddenly “snap” and attack impulsively, but instead are troubled people who spiral into crisis—and whose brewing plans for violence can be detected, explained, and potentially prevented.

These are among the reasons Chin Rodger eventually decided to speak out about what she did and didn’t notice, or misunderstood, before Elliot’s rampage. By sharing her experience with prevention experts, and by talking with me about a trove of previously unreported case evidence and details of Elliot’s life, she hopes to help foster a clearer understanding of his attack, and, with it, greater potential to prevent violence.

The deli mart in 2024, where Elliot fatally shot 20-year-old Christopher Martinez a decade earlier.

Philip Cheung

“Inside I was broken into a million pieces,” she recalled about the early aftermath. “It still tears me to pieces—reading about and reliving the events, going over all the conversations I had with him and everyone around him, his writings, his personal things. It’s not just the pain of losing my son but the horrible suffering his actions caused for so many. I will carry this pain for the rest of my life.”

She had always felt close with Elliot, who was intelligent and came across as quiet and polite. Diminutive from childhood, he struggled with developmental disabilities that made him acutely shy and awkward, and his parents moved him between various schools as they sought special education and therapeutic help. He was bullied, but prior to his attack had no history of aggression known to his parents or anyone else around him. It was hard for Chin to comprehend how well he’d hidden his innermost torment, and ultimately his suicidal and homicidal intent. Even today, she hasn’t felt ready to read all of his “life story,” or to go through his two handwritten diaries, which are part of his deeper trail that until now has been almost entirely unknown to the public. She has five sealed boxes of his personal effects sitting in storage, long ago returned to her by investigators. Digging further is often still too painful and heartbreaking, she says, yet she feels compelled to keep going because she believes in the value of spotlighting missed chances to stop Elliot’s plan.

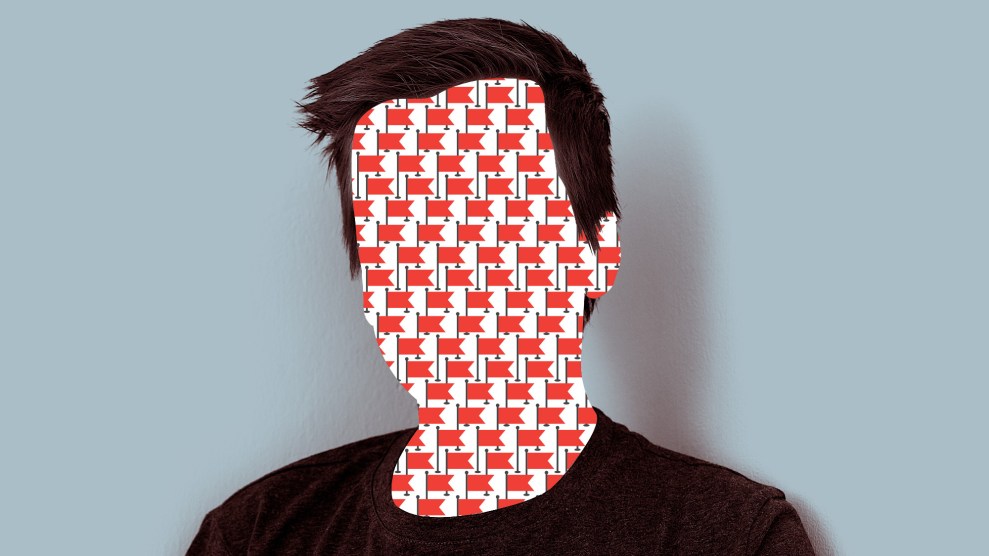

I began speaking with Chin in 2021 as I was finishing work on Trigger Points, my book about preventing mass shootings through the use of behavioral threat assessment. This emerging method has been adopted by businesses and government entities and is now required in public schools in 20 states. It’s a community-based approach that combines expertise from mental health, law enforcement, and other disciplines to intervene with troubled individuals who show signs of planning violence. Even as they descend into rage and despair, many mass shooters remain ambivalent about killing themselves and others—and most engage in observable warning behaviors well before they attack.

Therein lies opportunity to head off catastrophe. The red flags can range from communicated threats and changes in routine to fixation on grievances, guns, and previous killers. Signs of suicidality are crucial, as is evidence of preparation. Successful intervention usually begins after someone close to a troubled person feels worry or fear and reaches out to authorities for help. That’s where a threat assessment team comes in. Made up of psychologists, administrators, law enforcement, and other trained practitioners who meet regularly to handle cases, the team conducts interviews and gathers information to gauge the danger. Then, over weeks or months, they use constructive tools like counseling, social services, and education support to guide the troubled person away from what the field calls “the pathway to violence.”

Think of that person’s life and circumstances as a giant impressionist painting filling a gallery wall. People up close to it—a parent, a teacher, a peer—may notice a few striking details, but what do they show? A threat assessment team has the ability to make sense of the whole picture by stepping back and seeing how all those details come together. There is a well-known adage in the field: “You can’t connect the dots if you don’t collect the dots.” From Virginia Tech in 2007 to Isla Vista and beyond, many mass shootings have been marked by a disastrous lack of information sharing. People spoke up with alarm, but no threat assessment programs were in place to pull together the data and respond.

Threat assessment is about prevention, not prediction. Despite popular belief, there is no such thing as a set of demographic or personal characteristics for profiling potential mass shooters; though overwhelmingly male, they range widely in age, background, and circumstances. It is not possible to forecast with certainty who will commit violence—but experts can see when someone is at growing risk of doing so. The “profile,” so to speak, is a pattern of behaviors indicating danger. Using a method first pioneered in the 1980s, threat assessment teams have deterred scores, if not hundreds, of people who appeared headed for violence in schools, workplaces, and other venues. Often there is no crime to prosecute, and importantly, experts have learned that a supportive rather than punitive approach is more effective in many cases for reducing danger over the longer term.

About five years after Elliot’s attack, Chin discovered threat assessment while researching mass shootings online. When I learned of her interest from a source and contacted her, she waited months to open up. The first time we met in person near a sunny beach in Los Angeles felt a little surreal. Up walked a petite woman with shoulder-length brown hair and dark eyes who radiated a kindness and humor that were at first hard to reconcile with her burden. Her speech was soft, with a lilting sadness. We spoke for an entire day. She wanted to know more about the successful prevention cases I’d been chronicling for the book.

She felt haunted by questions of why therapy, social counseling, and various other efforts over the years to help her son connect with people had failed. After moving away for college, Elliot met with his social worker and sometimes a therapist during his visits home to LA. He’d been prescribed meds for depression and anxiety, though he wrote about refusing to take them. Chin hired an agency to provide Elliot with life-coaching in Santa Barbara; in his final year he met individually 29 times for walks and other activities with three young peer counselors, who encouraged him and focused on building his social skills.

Chin’s trauma was exacerbated by an enduring media-driven narrative that depicts her son as a totem of misogynistic evil, the putative leader of a violent movement made up of aggrieved men who call themselves “involuntary celibates,” or “incels.” Elliot voiced grotesque hatred of women in his writings and videos, and in his final year had posted comments on a fringe website that drew men from this online community. But, for Chin, the idea that incel ideology was the core explanation for what Elliot did seemed a distortion. She was determined to understand more clearly what had led him to carry out catastrophic violence and how it could have been prevented.

The public rarely hears from parents of mass shooters apart from brief statements of sorrow in the aftermath. (A notable exception was the mother of one of the Columbine school shooters in 1999, Sue Klebold, who became devoted to raising suicide awareness and later published a bestselling memoir.) The prevailing theme has long been that no one can see the violence coming, the parents included.

The remnants of a house party on Del Playa Drive in 2024.

Philip Cheung

But that theme no longer holds, especially in light of a recent tragedy that could remake the legal landscape. Earlier this year, the mother and father of a 15-year-old mass shooter at Oxford High School in Michigan were convicted of involuntary manslaughter—an extreme case in which they’d ignored their son’s mental deterioration and gave him a gun just before he attacked in November 2021. In many ways, that scenario could not have been more different from Elliot’s. The Oxford shooter was an openly distressed minor living at home who was given no mental health care but access to a weapon. Elliot, by contrast, was a young adult out in the world who got extensive counseling and family support and skillfully hid his intent. Both cases, however, speak to the role of parents as potentially key to prompting expert intervention.

In a decade-plus of investigating mass shootings, I had never before heard of a perpetrator’s mother making the grueling choice to become a student of her son’s case. None of the nearly dozen threat assessment experts I spoke with for this story suggested they thought that Chin, or anyone else in Elliot’s life, was at fault for failing to anticipate what happened. Yet, Chin came to believe that there had indeed been warning signs, even though she’d had no way of knowing back then what they were. She feels she can help spread awareness, especially for people whose own loved ones might be turning dangerous. “I hope my hindsight will be others’ foresight,” she says.

In 2020, she spoke with FBI experts to provide additional details about Elliot, and, in a unique development for the field, threat assessment leaders soon began inviting her to share her perspective at trainings. Those leaders caution against overstating retrospective conclusions, given that some warning signs are more reasonably identifiable than others prior to violence. But they concur that Chin has helped further the field’s knowledge of pre-attack behaviors and circumstances, and prospects for intervention.

People close to perpetrators often hesitate to seek help and will minimize or rationalize concerning behaviors, according to Dr. Karie Gibson, unit chief at the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit. In her view, Chin’s account is powerfully humanizing and will encourage others to come forward.

“I believe that prevention is possible right up until the attack happens,” Gibson told me, noting that because the public tends to regard the family members as monsters, “when you hear individuals [like Chin] tell their stories, and the personal impact, it challenges that stereotype and breaks it down. You see the realness of a mother or father, or a sister or brother connected to the individuals who go on to commit these attacks, and they also suffer in that reality.”

Chin’s experience illuminates a challenging paradox: While parents can be among those best positioned to notice warning signs, they are also likely to have the biggest blind spots to anomalous and disturbing behavior. Consider what it would really mean to realize one’s own child might be planning lethal harm. “A concerned parent may be looking for the positive, for things that are comforting, and that can cloud the ability to see certain things they may not want to see,” another threat assessment leader familiar with Elliot’s case told me.

The Starbucks where Elliot Rodger ordered a triple vanilla latte the evening of the massacre

Philip Cheung

Take what happened that night at the sushi restaurant. Elliot’s conspicuous change in demeanor and appetite had reassured Chin. But that shift in him was what experts call “unexpected brightening,” an indication of rising danger. Once a perpetrator becomes more resolved and prepared for a suicidal attack, a heightened sense of purpose and calm sets in. Elliot exuded less turmoil because he was finally ready to act.

The recently paid-off parking ticket was also not what it seemed. Whereas Chin saw her son taking responsibility, the writings and videos Elliot left behind suggest a different potential motivation: He was keen toward the end to avoid any attention from authorities, lest they possibly discover his plans. His skills of manipulation and deception had also played into the tragic miss when police went to his apartment for a welfare check in response to Chin’s concerns, just a few weeks before the mass murder.

Psychologist Stephen White, a top expert in the field who authored a definitive case study on the attack, says Chin’s engagement with threat assessment reflects extraordinary courage and resilience. “It’s the ultimate curse to be the parent of a mass murderer,” he says, with the entire world rendering a judgment of failure and culpability. “It’s confronting an enormity of shame that you’re left with. You either descend into letting that bury you, or you do the bleak work of redefining the meaning of your life. She made it her purpose to try to help, and she has.”

Those first days after were brutal. The drive back to LA to tell Georgia the crushing news. Anguished thoughts of the victims and their families. A swarm of media outside the house, then an escape to a local hotel. A hasty family meeting at a Denny’s joined by a friend of Peter’s who would help handle PR matters. A call overseas to her own mother, who’d helped care for Elliot as a child, so she wouldn’t find out from watching TV.

A gutting emptiness. The death of her son.

Chin and Peter cooperated exhaustively with police, but they struggled with how else to respond. Peter wanted to speak out and express the family’s sorrow. Chin wanted to remain in seclusion, though she recognized the pressure Peter felt to comment publicly—the intense media coverage was also spotlighting his career, particularly his recent work as an assistant director on The Hunger Games, the blockbuster tale of youths forced to hunt down and kill each other. In 2012, Elliot had joined Peter on the red carpet for the film’s LA premiere. Graphic Hollywood entertainment had been baselessly blamed for causing mass shootings ever since the Columbine massacre. One prominent film critic wrote a column arguing that Elliot’s “delusions were inflated, if not created, by the entertainment industry he grew up in.”

A month after the tragedy, Peter sat down with Barbara Walters on ABC’s 20/20 to convey the family’s condolences and devastation. He described Elliot’s long-standing issues and the family’s various efforts to help him. When Walters prodded him about public reaction, he said Elliot was “far from evil” but that “something happened to him, and then I think he became very mentally ill.” He emphasized that no one had ever thought Elliot would become violent: “What I don’t get,” he told Walters, “is that we didn’t see this coming at all. None of us.” (When I contacted Peter this spring, he declined to comment further.)

It was clear from the ABC interview that Elliot’s parents, aided by educators and therapists, had struggled to help an increasingly troubled kid—but the broadcast also engaged in a form of TV sensationalism that is now more understood to be unhelpful or even reckless in how it pushes myths about mass shooters. It played multiple segments from Elliot’s videos and used news clips, witness interviews, and voiceover narration to depict him as “a madman,” “psychotic,” “the face of the devil,” and a quiet boy turned “monster.” This reinforced the notion that mass shooters are inexplicable demons who can’t be stopped—and who can indeed capture the major media attention many crave.

Mourners at a “memorial paddle-out” after the Isla Vista shooting.

Peter Vandenbelt/Santa Barbara News-Press/Zuma

In the aftermath, the world made little sense to Chin. She wouldn’t turn on a TV unless it was set to a cooking channel. She wanted to reach out to the victims’ families but feared that would only hurt them more. A mother of one of the murder victims sent her a condemning letter that was shattering to read. Only later would she know about the press conference the day after the carnage where anguished father Richard Martinez assailed politicians and the National Rifle Association for complicity in his son’s death. “They talk about gun rights—what about Chris’ right to live?” he beseeched in his wrenching remarks. “When will this insanity stop?”

Martinez agreed to a meeting with Peter at a friend’s house 10 days after the massacre, the details of which they kept private at the time.

“I got a box and put together a bunch of Chris’ stuff,” Martinez told me recently. “Pictures of him, trophies and sports jerseys, different things about Chris. Mainly a lot of photos.” They sat together in the backyard for more than an hour and Martinez did most of the talking, he recalled. Peter appeared deeply saddened and sorry. “He didn’t really talk about his son. I had the table between us full of Chris’ stuff, and I was just showing him and telling him about my son. It just felt like the right thing to do. I wanted him to know my son. I wanted him to understand our loss.”

Survivor Bianca de Kock, recovering from five bullet wounds, had also decided to speak out in the early aftermath, to grieve her murdered friends: “They were both two very incredible, beautiful people,” she told a TV reporter through tears, “and that’s how I want them remembered.” The reporter noted in the broadcast that de Kock’s parents had acknowledged that Chin and Peter also must have been “hurting terribly.”

Chin felt she would never get over what happened. “For many, many months I was just so numb,” she recalled. But an entry in her personal journal five weeks after the massacre, from just after she’d taken Georgia to stay temporarily with family abroad, suggested something more. “If you look at me now,” she wrote, “you’ll see the saddest human being on earth. But my spirit is OK, it is strong.” She would focus on caring for Georgia, and beyond that would withdraw into work, her small circle of friends and family, and her Buddhist faith.

After Georgia went away to college, Chin began to immerse herself in reading about reconciliation and violence prevention. Eventually she began reaching out to others who knew calamitous violence. She contacted Scarlett Lewis, whose 6-year-old son, Jesse, had died in the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary in 2012, and who was working to boost social-emotional learning in schools. Amid tearful conversations, the two grew close from opposite ends of shared horror.

“I think it was healing for Chin to be able to talk to a victim’s parent who understands and has compassion,” Lewis said when we spoke. “I love Chin like a sister. We are sisters in grief.”

Chin at Sandy Hook victim Jesse Lewis’ grave in 2023

Courtesy Chin Rodger

Of Chinese descent, Li Chin Tye grew up in Penang, Malaysia, and moved at age 17 to England, where she trained in health care and later worked as a unit nurse on the productions of The Princess Bride and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. A photo from the late 1980s that circulated online after Elliot’s attack showed her with George Lucas, Harrison Ford, and Michael Jackson. She met and soon married Peter, whose father was renowned British war photographer George Rodger, and Elliot was born in July 1991. When Elliot was 5 and Georgia was an infant, the family relocated to California.

By then, Elliot was showing behavioral issues. He was shy and sometimes withdrawn, and struggled with speech. He was prone to repetitive behaviors like tapping his feet and was sensitive to overstimulation—the colorful chaos of Disneyland made him cry intensely. His parents, who would soon divorce, began what would become years of therapeutic and special education support, seeing some progress as they tried different schools and as Elliot made some friends and his speech improved. But he was bullied and continued to struggle socially. The mother of an elementary school friend quoted in the New York Times remembered Elliot as an “emotionally troubled” boy who would come over to their house and just hide, leaving her and her husband apprehensive.

In high school, Elliot was diagnosed with “Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified,” a term covering a range of behavioral issues that today are categorized under autism spectrum disorder. His evaluation scores, however, landed below the threshold for ASD. The broad PDD diagnosis was intended to qualify him for special education resources, an approach sometimes used by psychologists seeking help for a troubled kid.

The ambiguity of whether Elliot was on the spectrum only underscores an egregious failure of the media frenzy—one headline labeled him as “Autistic Santa Barbara rampage killer.” Worse than just highlighting an unverified claim, various coverage misled about the possible role of the disorder and amplified a damaging stigma. Less than two years prior, the Sandy Hook massacre had stirred fear around autism when the public learned that the 20-year-old shooter had an ASD diagnosis among multiple conditions. But implied blame on autism is fundamentally wrong, as White and several colleagues made clear in research published in 2017 in the Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. “Most individuals who fall on the spectrum of ASD are neither violent nor criminal,” they wrote, affirming multiple previous studies.

That echoed decades of research showing that the link more broadly between mental illness and violence is small and has no predictive value. In an obvious basic sense, no mass shooter is mentally healthy, but the vast majority of people with mental health struggles or developmental disorders do not commit violence. Any influence of ASD among some killers studied by threat assessment experts is nuanced and requires an understanding, crucially, of comorbid factors. As White found in his case study, Elliot’s situation involved “likely features of autism spectrum disorder, narcissism, psychopathy, and depression. A predominant theme is the role of extreme social isolation and severe, pathological envy, fueling the eventual attacks.”

Surfboards stored alongside a building at UC Santa Barbara

Philip Cheung

The media skewed the picture of his mental health in further ways: White and other experts later concluded that the large volume of forensic evidence showed that Elliot—notwithstanding how Barbara Walters had labeled him for an audience of millions—was not psychotic, a state of mental disconnection from reality. The myth that mass shooters are all insane and lack command of their actions strongly implies that they are driven by hallucinations or delusions, yet psychosis is present in only about 5 percent of all cases, according to in-depth FBI research and a study by Columbia University psychiatrists.

In reality, many mass shooters are just deeply isolated, angry, and desperate. They have decided that death is their only way out and have settled on their justification for taking others with them. Most key for prevention, then, is not a mental health diagnosis per se, but instead the recognition of a behavioral trajectory and its context. How might Elliot’s situation and lengthy planning for the attack have been identified and addressed effectively?

After mass shootings, we frequently hear that mental health treatment is paramount, a generalized assertion often used to deflect from debate over gun laws. But as Elliot’s case makes evident, conventional therapy and counseling are no magic solution when it comes to detecting and preventing planned violence.

“In a lot of cases you’ll see attempts at intervention but they aren’t landing, and that’s because something key is missing,” says FBI unit chief Karie Gibson, who is a licensed clinical psychologist. Threat experts have found that for many potential attackers, only a “thin line” separates suicidal and homicidal intent—so a priority is to discern whether a person has crossed over and is driven by both. “Someone could be in therapy but not feel comfortable or safe enough to share those deepest, darkest thoughts,” she says. Threat assessment extends concern and care but also collects information more broadly—background checks, scrutiny of social media, interviews with family, peers, and others—to evaluate the significance of specific behaviors. That includes understanding the individuals’ core grievances, Gibson adds, even if unfounded. “Whether what happened to them is real or only perceived, that’s a fact they’re living by.”

So much of Elliot’s inner rage was focused around his perception that the whole world was rejecting him. But this was wrapped up in his acute “shy narcissism,” according to White, which kept his shame and envy mostly hidden until near the end.

After high school, Elliot attended local community college briefly but was getting nowhere with school or social life. Chin and Peter hoped to expand his horizons when he expressed interest in moving 70 miles up the coast to enroll at Santa Barbara City College. Emails he wrote during this period show he felt bitter toward Peter, whom he blamed for failing to teach him how to be a successful “gentleman”—an oddly aristocratic term Elliot used in his 137-page screed that would later feed the incel mythologizing of him.

I contacted several people who worked to help Elliot during his two-plus years away from home: Gavin Linderman, the young LA social worker who’d helped instigate the welfare check in Isla Vista and called Chin the night of the massacre, did not respond to multiple inquiries. Nor did a psychologist in LA who treated Elliot periodically over the years, including near the end. A director of the agency whose three young counselors coached Elliot in Santa Barbara spoke with me, but asked not to be named. She said she noticed from the start that Elliot was keenly aware of how hard he struggled to be more normal socially, and that he had an edge to him. She explained that he liked his two male counselors but also envied their social charisma and sometimes made bitter comments in their presence about girls. He connected well with a kind female counselor, but resented the implication he needed paid female companionship.

“He deeply wanted a fairytale ending and it wasn’t coming,” the counseling director recalled.

Mental health specialists know that high-functioning youth with disabilities can become more aware of lacking progress as they grow older, which can fuel anxiety and feelings that they won’t succeed in life. Threat assessment calls this “downward drift,” says White. “That can contribute to depression, a sense of despair.”

In Elliot’s final year, Peter had enlisted a longtime friend, Hollywood producer and screenwriter Dale Launer, to try to help mentor him. The two corresponded by email and met up in LA, but that led nowhere, according to Elliot’s writing in “My Twisted World” and Launer’s own account in an essay and interview with the BBC. Launer long knew Elliot was troubled and by this point noticed he had an unhealthy entitlement about women. “We met three or four times, for a couple of hours each time,” Launer told the BBC, “and each time I had to index my expectations lower and lower.” He saw Elliot as paralyzed by timidity, and suggested he try an acting class to overcome it, but said he never got an inkling of Elliot’s “violent nature.” (Launer did not respond to a request for comment.)

I found no evidence that anyone in Elliot’s orbit ever thought he might hurt or kill people. His suicidality, a key warning factor in threat assessment, also was elusive to friends and family. Chin told me repeatedly in our many interviews that she never felt Elliot wanted to take his own life. “It’s very, very difficult to see all of this when you are in it,” she reiterated. “Now I can see that, but at that time, no way.”

The counseling director told me that when the male counselors had brought up some dark outbursts from Elliot, she didn’t think too much of it because young people facing social deficits often feel discontent and act out: “I live in the world of disabilities. Unusual behavior is all day long.”

“Chin was the most engaged parent I’ve ever seen,” she added, noting that social counseling often can succeed with high-functioning individuals. Still, she’d sensed in the final months that they were in over their heads. “We’re trying to apply social skills with this guy,” she said. “I felt that this whole situation was way beyond what I was brought in to do.”

It’s important to remember that this was early in the era of escalating mass shootings, when threat assessment was unknown to the public and even to most in mental health and law enforcement. White pointed to the implications in his study of Elliot’s condition: “Such complex difficulties are not the domain for ‘life coaches’ or ‘social skills counselors,’ however well-intentioned.”

Elliot also showed positive signs. His social counselors reported that he spoke of interest in political science clubs and volunteer work, and a document charting his goals included his aspiration to transfer to UCSB. Based on such feedback, the counseling director told Chin in late 2013 that Elliot seemed “headed in the right direction.” They saw him trying hard to improve, but he was also propping up certain illusions of progress. And his diaries were just the start of what he was concealing.

The term traces back more than four decades to FBI research on serial killers and certain behaviors they exude that point to their crimes. Later applied to mass shooters, it evokes how perpetrators signal their plans to attack. Threat assessment experts have found that these communications can be subtle, taking the form of innuendo, bragging, blame, or predictions. Veiled or more explicit threats show up in talk, writings, online posts, or other personal expressions—a few cases have even involved tattoos, including in homage to a Columbine shooter. Hours before gunfire erupted at Oxford High in Michigan, whose district had no threat assessment team, a teacher found a drawing of a shooting by the perpetrator labeled with comments such as “Blood everywhere” and “My life is useless.” The behavior arises from personal deterioration, as a cry for help, or both.

Elliot’s case also exemplifies a more recent insight. In 2018 research examining 63 active shooters, FBI experts found that despite the perpetrators’ self-isolating or erratic behaviors, four out of five had dodged empathetic or suspicious questioning from concerned people around them. (School shooters often claim to be just “joking” with their threats.) The research confirmed a long-standing theory: Many shooters engage in both leakage and subterfuge.

If Elliot’s troubling behaviors had come to the attention of a threat assessment team, odds for effective intervention would have jumped. He announced his intent most clearly via email and YouTube at the last moment, but other leakage appeared in his diaries going back more than four years, and in talk and actions he recorded on cellphone videos in the final months. Threat assessment leaders I reviewed this material with said his planning could have been uncovered through empathetic questioning and reviews of his online posts. “We certainly would have encouraged him to talk to us about what was burdening him and pursued other lawful ways to look into his communications,” one longtime practitioner told me.

Students at a house party on Del Playa Drive in 2024

Philip Cheung

The diaries reveal Elliot’s thinking contemporaneously and more reliably than his autobiographical screed, which he wrote in the final months and to some extent is a retrospective performance of his grievance and rage. That’s made clear by another document, “Life Story Structure Notes,” in which he outlined methodically how he would depict his early childhood as blissful yet tainted by grief, anger, and a purported focus on getting revenge against a social “enemy” at the tender age of 6. He completed his performance the day before he struck, when he parked at a palm-lined beach and recorded two takes of his final video announcing his attack. The first version of the seven-minute diatribe was disrupted by a jogger going by. The second version, the one he posted, was smoother, with his face lit more cinematically by the setting sun. “I’ll be a god, exacting my retribution on all those who deserve it,” he declared with an almost cartoonish villainy.

This final video was his bid to broadcast omnipotence in place of failure. But for a long time prior, a part of Elliot appears to have wanted his plans discovered. “I didn’t write about this before because I was scared someone might find and read my diary,” he stated in a June 2013 entry noting his purchase of a second gun and plans to stockpile ammunition. And yet, knowing he planned to attack in November (later postponing that to the following spring), he chose to create that evidence months in advance: “Since the Day of Retribution may be happening soon, perhaps even this year, I figure I’ll write it down now.” Later that June he wrote, “I am now armed and it makes me feel powerful,” describing a suicidal mission to “slaughter all of my enemies.” In that same entry, though, he also described feeling “sick with anguish” and a desire to escape his predicament.

“One of the values of this case is how extensively he documents his ambivalence,” notes White.

Such ambivalence is common among perpetrators, a pattern first highlighted two decades ago in the Safe School Initiative, a landmark federal study done by threat assessment experts after Columbine. That investigation of 37 school shooters showed how some had wavered and likely would have been receptive to help. Most young shooters leak their intent to peers, who seldom fully grasp the situation or tell an authority figure. By Elliot’s own account, he voiced biting contempt for girls to a friend he’d grown up with and then assuaged him when the friend responded that Elliot shouldn’t do anything “rash.”

His fantasies of vengeance were intercut with desperate longing throughout the nearly 200 pages of his diaries. “I really, really wish there was a way out,” he wrote in another entry. “Perhaps I should give the world another chance…I don’t want to have to resort to violent, final retribution. I want a happy life!”

“I think deep down all he really wanted was to find someone to love and have a family with, and he would say that,” Chin told me. She recalled talking with Elliot when he was attending community college in LA and hanging out at a local Barnes & Noble. One day he described looking out the window at a father helping his young kid from the car. “I wish I could have that,” he told her.

A week after the massacre, Chin received a letter from the young female social counselor who had met with Elliot over several weeks in early summer 2013. She recounted how he had opened up on their walks together, sharing laughs and bonding over an appreciation of the coastal scenery. “This is the Elliot I remember and knew,” she wrote. “A gentle, reflective, curious, clever, conscientious, and kind man. I am so incredibly sorry for your loss.” She said she’d been sad to move away from Santa Barbara and stop working with Elliot.

Students at UCSB in 2024

Philip Cheung

Later that summer Elliot was focused on “a last ditch effort” to lose his virginity before his 22nd birthday. On July 20, 2013, he got up his nerve with some shots of vodka and entered the Saturday night scene along Del Playa Drive. Around 11:30 p.m., he ventured into a house where college kids reveled in beer pong and hip-hop tracks from a DJ. Feeling ignored, he went back outside and up onto a wooden platform running along the top of the front fence line. These makeshift structures were common on Del Playa, a place for partygoers to hang out and drink while overlooking the action on the street. Around him he saw Isla Vista at its “wildest state.” When a few others came up on the platform, Elliot began insulting them—and then tried to shove a couple of the young women off the roughly 8-foot drop, toward the street. He failed and ended up on the pavement himself, fracturing his ankle. It’s unclear whether he was pushed off by guys who intervened, as he later claimed, or he jumped off, as one eyewitness said. He made his way to another nearby house party, where he also got into a confrontation. He was pummeled by a group of “obnoxious brutes,” he later wrote, only to drag himself back to his apartment in the wee hours, alone.

Later that morning Peter drove from LA to take Elliot to the hospital and help him file a police report. (No one was ever charged.) He was bruised and had facial abrasions and a swollen left eye. His ankle needed surgery. But even worse for Elliot was the shame.

“AAARGH!!! I sit here in defeat, and I am fuming with rage,” he wrote two weeks later, recovering from surgery back in LA. He wrote that his actions had been wrong, but he was horrified that “everyone in Isla Vista saw what happened” and no one had come to his aid. “That was the final straw,” he continued. “I ended up beaten, crippled, and humiliated.”

A neighbor interviewed by CNN after the massacre would recall seeing Elliot when he came back from Del Playa Drive, beaten up and sobbing uncontrollably. According to the neighbor, Elliot said, “I’m going to kill all of them. I’m going to kill myself.”

“Shame is a core motivator for many mass shooters,” says White, who observed in his case study that Elliot was mired in “pathological, insidious envy—a painful state of unworthiness related to shame that leads to the wish to destroy goodness in others.”

To some degree Elliot knew this himself: “Jealousy and envy,” he wrote in his 137-page screed, “those are two feelings that would dominate my entire life and bring me immense pain.”

In addition to his hostility toward his roommates, who were of Asian background, some of Elliot’s writings suggested self-loathing over his mixed racial identity. This included his belief that girls should be more attracted to his English heritage than they would be to “full-blooded Asians”—the “gentleman” side he imagined cultivating. Experts told me perpetrators respond to futility and shame by seeking a sense of power and control through violence. Often that includes trying to shape public perception of their attacks with bids for media attention, such as voicing racism or hateful ideology.

The party ordeal was also pivotal in Elliot’s attempt at violence. On prior occasions he had tried to splash drinks on young couples he saw in public and then quickly fled, a way he would feed his envy and anger. But this time he had sought to cause major physical injury—an escalation known as “novel aggression,” essentially a test of one’s capacity to do harm. These risk-taking behaviors also indicated Elliot’s suicidality, White told me.

As mass shooters become consumed with anger and despair, they build justification. Various extremist ideologies can serve to validate their conclusion that the only answer to their suffering is lethal violence. For years, Elliot had harbored suicidal thoughts and blamed others for his pain. But his humiliation on the party scene was a key triggering event, and it soon combined with a stirring interest in online extremism.

Evening in Isla Vista, May 2024

Philip Cheung

before his attack, Elliot began engaging with an obscure website frequented by incels, a subculture of disaffected men who lament their lack of romantic success and blame women for denying them sex. Immediately after the massacre, extremism researchers and journalists highlighted disparaging comments he’d posted online. They cited his menacing final video and his widely republished “manifesto,” as the media called it. (Though rife with ugly rants against women and grandiose ideas of violence, the book-length work is more accurately described as an autobiography of sorts.) The attack also compelled women to share stories of misogynistic abuse they’d suffered in their own lives, marked by the viral hashtag #YesAllWomen.

Internet trolls depicted Elliot as the iconic leader of an incel “revolution,” which he had said in one comment “needs to happen.” He’d posted a couple other comments about provoking fear in women and “struggling as an incel.” This drove a pat explanation of Elliot’s self-identity and motive. The media, academics, and policymakers have run with this narrative of him ever since.

The reality of Elliot’s connection to incels is more complicated. Mass shootings inevitably set off a clamor to blame an ideology as the fundamental cause, often fed by the perpetrators’ social media, but rarely do thorough investigations produce any such clear explanation. From a threat assessment perspective, Elliot’s hyperbolic misogyny is better understood as the particular way he found to channel his long-brewing suicidal despair.

Though his comments referencing incels were seized upon to show that his violence arose from that world, there is substantial evidence to the contrary. He never once used the term “incel” in his voluminous diaries or other private writings, and some of his online comments suggest he did not identify as one. While incels often attribute their failures to what they see as their physical and genetic inferiority, Elliot asserted his sense of superiority: “How dare you speak to me like that,” he retorted when one commenter insulted his looks. “I am perfection incarnate.” In a final comment posted two nights before the massacre, he told off users who labeled him a “low-class incel,” linking to video of himself accompanying his “high status” dad and stepmom at the Hunger Games premiere. “You’re all jealous of my 10/10 pretty-boy face,” he wrote. “This site is full of stupid, disgusting, mentally ill degenerates who take pleasure in putting down others. That is all I have to say on here. Goodbye.”

He appeared to engage in these forums primarily to fuel his anger and justify ideas for violence that he’d nurtured for at least a year before this activity, as his writings show and experts affirmed to me. That is, incel forums were not the source or cause of Elliot’s violent planning, but rather a tool he used to psych himself up as he prepared to act. He would also rewatch his self-recorded video rants over and over to boost his rage and resolve, case investigators told me.

This suggests that when it comes to preventing future massacres, explaining why people commit these crimes—the often murky question of motive—may ultimately be secondary to knowing the process of how they reach the point of carrying out an attack. Put another way: Elliot’s engagement with incel forums was one of many steps he took along his way to a specific form of suicide. Many mass shooters are people who have decided to end their pain by also taking out others they feel have wronged them—that’s the crossing over of the “thin line”—whether they justify their suicidal nihilism with misogyny or other strains of extremist thought.

Chin recalled Elliot telling her about the websites he’d found, but she wasn’t tech savvy and paid little attention, figuring it was “just some harmless online activity” that young people did. “I wish I’d investigated more,” she said. “I think he was telling me, ‘Look, Mom, there are other people suffering like me and this is what they are.’ But I don’t think he saw himself as one of them—he saw himself as opposite.”

The totality of case evidence does not support the idea that Elliot sought or expected to lead a violent incel movement, White told me. “He wrote well, and he used some language about social change, but he knew it was grandiose. It wasn’t some grand philosophy or manifesto. He was talking to himself about his own pain, and falling into his self-loathing.” White added that much commentary citing or analyzing Elliot’s case does not hold up from a threat assessment perspective. “You see all these articles about him from the standpoint of sociology and so on, focusing on the misogyny, and then they wander into ‘This is what caused the attack.’”

The narrative of Elliot as incel ringleader distracts from what can be learned about prevention from his case—and even worse, it fuels attention-seeking imitators. Since the Isla Vista massacre, dozens of plotters and attackers have cited incel ideology or Elliot directly as their inspiration (including in several alarming cases threat assessors have shown me that are not public). Chatter about Elliot has metastasized on incel forums, where he has a “martyr-like importance,” according to researchers. A 2018 van attack on pedestrians in Toronto that killed 10 people and injured 16 others, frequently highlighted as the deadliest incel case, stands as a remarkable example.

“The Incel Rebellion has already begun!” the 25-year-old perpetrator, Alek Minassian, posted on Facebook as he began his rampage. “All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!”

Interviewed by police after his arrest, Minassian echoed Elliot’s own story, insisting that he, too, had been humiliated at a party by women who rejected him in favor of “obnoxious brutes.” He also said he’d communicated online with Elliot prior to the Isla Vista attack. The media ate it up. A Rolling Stone headline declared Minassian was “Radicalized by Incels,” atop an article parroting his claims from the police transcript.

It was all a ruse, as he later admitted to mental health practitioners who evaluated him for trial. He told them he wanted to become an infamous killer rather than “rot in obscurity.” He believed he could achieve “upgraded” notoriety by focusing on Elliot and using associated catchphrases “to boost my name.”

The trial judge in the Minassian case ultimately ruled that he was cognizant of his crimes and that his incel motive “was a lie.” That outcome, more than two years after the van attack, drew far less media attention than the story that Elliot’s massacre directly inspired Minassian’s own. (Even some threat assessment experts I flagged this for were not aware.)

By then it was also too late to stop a grim compounding effect. A 17-year-old who attacked two women in Toronto in 2020 with a large knife, killing one, had cited Minassian as his own inspiration. He too sought notoriety, and had carried a handwritten note: “Long Live the Incel Rebellion.”

Essential to threat assessment research is building a detailed panoramic view of a case subject’s life, to conduct what the FBI’s Karie Gibson calls an analysis “from cradle to grave.” In the earlier days of social media, it was rare for a mass shooter to leave behind a large trove of lucid personal evidence, and that made Elliot’s case an opportunity. I’d long compiled research on it myself, some of which raised questions about the role of the location where Elliot carried out his attack.

On a cool spring morning in March, as the pillowy marine layer began to lift over Isla Vista, I walked the blocks of Del Playa Drive where the catastrophe played out. The shabby party houses where he’d gotten hurt looked unchanged. No one was home at the one with the platform for hanging out at the fence line, which had a ragged couch sitting on top of it. Just across the street, behind facing houses and an apartment complex, the bluffs dropped down several stories to the Pacific crashing below. It was midweek, but along the block the densely parked cars, surfboards standing against a wall, and music drifting from a nearby balcony all suggested only a brief morning lull to party life. It was from one of these balconies that witnesses had heard the final gunshot and watched the black BMW crash.

A short distance into the center of town, at the Starbucks where he’d gotten his last latte, college kids in sweats and hoodies scrolled on their phones and talked about spring break plans. I wondered if they even knew what happened to some of their counterparts here a decade ago.

Soon I met up with Joe Schmidt, the lead detective on the case, now a lieutenant with the sheriff’s office. Also joining us in his unmarked SUV was his colleague Dr. Cherylynn Lee, a clinical psychologist and threat assessment expert who leads the department’s Behavioral Sciences Unit, developed in the years since the tragedy.

“The freshmen who are here now were 8 years old when it happened,” Schmidt said, as we began retracing the path of the carnage. “So they might’ve heard about it, but most of the people who I ask that question have no idea. I’m always taken aback, because to me it feels like it happened last year.”

Behind the wheel, in casual sheriff’s tan and green with a baseball cap on his clean-shaven head, Schmidt recounted from an encyclopedic knowledge of the case. He has briefed law enforcement nationwide ever since on lessons learned. He went through the names of every victim injured or killed, what happened to them, and where.

We stopped to look at a bullet hole that still marks the top of a cooking range inside the deli mart, then two others pocking the exterior wall of a building along the route to Del Playa Drive. College kids whizzed by on bikes and skateboards, past the sandwich shops and more apartment buildings. We paused at a small park where four officers had fired on the black BMW, trying to stop it, then arrived at the house on Del Playa where the ordeal had ended, a palm tree out front recognizable from the news photos.

This was just a college town. I tried to reconcile that as I thought of the endless media stories on incels, all the airtime his sinister video and “manifesto” had gotten, the heated debates about Hollywood and misogyny. I asked Dr. Lee what she thought was most important to know about what led to the attack.

“It’s suicidality and isolation without a doubt,” she said. “That is the constant in upwards of 95 percent of the cases we’ve worked at the Behavioral Sciences Unit. The persons are not well connected socially, and they’re often alone and have thoughts of killing themselves.”

It was also clear that Isla Vista was not a good place for Elliot to be. In effect, he was living in the center of concentrated insecurity, putting right in his face what he came to feel he could never have. “If his grievance is he can’t connect with people, and people are around him all the time and he’s constantly isolated, he’s living in that environment 24 hours a day, 7 days a week,” Lee observed.

Not long before the tragedy, Chin began to realize this herself, and she wanted to get him out.

In August 2013, nine months before the massacre, Elliot was recovering back home from his ankle surgery and Chin was focused on boosting his confidence for the fall semester. He agreed to meet with a trusted therapist who’d treated him when he was younger. He looked happy when a childhood friend visited. He’d been pining for a flashier car than his old used Honda, so even though money was tight, Chin decided to buy him a used black BMW coupe. It needed some repairs, but would give him an appearance he craved. She didn’t know he’d grown fixated on wealth as the key to getting a girlfriend; she’d laughed it off when he urged her to remarry someone rich, and he never said a word about the many Powerball tickets he’d been buying.

“Now I am one of them, and it certainly boosts my self-esteem every time I go out,” he wrote that October, focused on Santa Barbara students who drove luxury cars. “I’m hoping that since I now have a cooler car than most kids at my college, I’d have a chance of attracting a girlfriend.”

By the following semester he was secretly quitting his classes, clashing with his roommates, and writing his rageful “life story.” He shared a carefully selected sample with Chin, his depiction of an idyllic childhood in England, and, impressed, she encouraged his stated aspirations to write a novel.

One night in February 2014, Elliot called Georgia while wandering the streets drunk and railed about girls ignoring him. His sister talked him down and had the awareness as a high school senior to know that the social scene in Isla Vista was toxic for him. She’d long worried about her brother being there, she later told me.

Chin consulted with Elliot’s therapist, with social worker Gavin Linderman, and with the counseling director in Santa Barbara, then called Elliot and urged him to leave Isla Vista temporarily. She offered him a choice: She would arrange for him to go to a high-quality residential treatment center where he could relax and get daily therapy, or he could come stay at home with her and see his therapist and social worker for an intensive period of help. She followed up with an email reiterating her love and confidence that he would overcome his struggles.

“Dear Mother,” Elliot soon wrote back, “I would love the chance to try and get something positive out of my time here. I now realize that time is running short and I have to do something with my life. If you agree to continue with my rent, I promise I will do everything I can and turn my life around. I will study hard, complete the courses that I’m halfway through, and spend the next four to five months here more productively.” He said he’d made new acquaintances and was keeping busy with his social counselors, and he promised to see his therapist and his social worker when back home. “Please let me prove to you that I can make it here.”

Chin spoke further with the professionals helping Elliot, who suggested that she’d done her best to give him options and advised her to support his goals for finishing school. There was no legal basis to make him leave or get more intensive help, the counseling director recalled. “He’s an adult. He can just say ‘no.’”

“I relied on them to guide my thinking,” Chin said, emphasizing that she wasn’t casting blame—and that none of them could’ve seen the whole picture. No one involved had the training to grasp the rising danger, or a way to share Elliot’s concerning behaviors in the methodical manner a threat assessment team would have. They didn’t know or imagine that he’d been stalking a sorority house and buying guns; their focus was on normalizing his experiences and helping him gain greater independence.

Tragically, that just allowed him to isolate further, the counseling director now believes. Her young staff was actively meeting up with Elliot, but he still had a lot of time, she said, “to sit in his own thoughts.”

On the morning of April 18, 2014, Elliot recorded himself driving an hour down the coast to Oxnard, his car stereo blaring the Motels’ “Suddenly Last Summer,” a 1980s pop hit romanticizing youthful innocence and the loss of virginity. He arrived at a familiar destination: Shooters Paradise. It was one of half a dozen trips he made to gun ranges in the final four months, where he had paid upward of $100 for a lane, targets, eye and ear protective gear, and hundreds of rounds of ammunition.

Back in Isla Vista that evening, he recorded two videos on his phone. They contained no explicit threats, but further revealed how the humiliation at the party the prior summer kept eating at him—and showed him engaging in stalking and surveillance.

Elliot, in a video he made prior to the attack

YouTube

He cruised the streets starting around 10:30 p.m., narrating his grievances as his phone mounted on the dashboard recorded the scenery. “Every time I drive through this place I am overcome with rage,” he said, soon turning onto Del Playa Drive. Partygoers walked in the street or rode bikes or skateboards in the balmy night air. He slowed the car as he approached a pair of houses, one festooned with string lights and the next fronted by a platform at the top of the fence line. “Look,” he said, “that’s the house I got beat up at when I walked in on the party.”

He rehearsed his anger as he continued along the block. “Ah, here we go, look at this,” he sneered as he passed a trio of college girls heading for the party house. “Groups of hot young sluts who would just reject me.”

He recorded a second video as the area grew more crowded, lamenting the “sick and evil” town and shouting “You’re an asshole” at a guy walking in the street with two girls. The footage of him slow-rolling past partygoers suggested a chilling prospect he’d written about: “Isla Vista on weekend nights was always filled with my enemies walking right in the middle of the road. They would be easy targets.”

Five weeks later, he would ram several victims along Del Playa, then end it all just a block from the house where he’d fallen from the platform.

Elliot kept the Del Playa footage concealed, but by the end of April, his picture of calm and stability started to slip. Chin was used to him responding to her texts and calls, and after he went silent for several days she grew worried. She searched online and found a video he’d posted: Dressed in his favorite blue Hugo Boss shirt and Armani sunglasses, he stood by a canyon road in Montecito extolling the scenery, complaining about girls ignoring him, and talking up his looks and personality. The six minutes included flashes of resentment and despair, and objectively would have struck at least some viewers as troubling or strange. But Elliot also expressed sincere longing, and nothing openly menacing like what was to come.

Chin would later conclude this juncture had been a major blind spot for her. Elliot posting a recording of himself was new, and though she noted his frustration, it struck her as part of his efforts to overcome his social deficits. “He was trying so hard, and I thought this was him evolving and putting himself out there more,” she recalled.

Still, Chin felt unsettled and feared Elliot wasn’t responding to her texts and calls because he’d gotten lost or had an accident on one of his sunset hikes. She again reached out. The Santa Barbara counseling director remembered the video as “very ominous” in tone, she told me. “It was definitely a window into his psyche at that moment,” she said. Chin also called social worker Linderman, who raised concern about self-harm and said he would call the crisis hotline in Santa Barbara right away to ask for help.

What was said on that call remains unclear, but when sheriff’s deputies arrived at Elliot’s apartment that evening of April 30, they found him to be “shy, timid, and polite.” He told them that he was lonely and that the video, which they hadn’t seen, was just a way of “expressing himself,” investigators later wrote. After they spoke with him for a few minutes at the door, his arsenal hidden just inside, a deputy suggested he call Chin. He coolly explained that she was a “worry wart” as he dialed her on his cellphone.

“Mom, why did you call the police on me? There’s nothing wrong, I’m just busy. Here, talk to them.” He handed his phone to the deputy, who asked Chin if the video made her concerned about Elliot harming himself or others. She said no. The deputy affirmed for her in the brief exchange that Elliot appeared fine.

The facts known at the time didn’t provide a basis to use California’s law allowing for temporary custody for a mental health evaluation, recalled Lieutenant Joe Schmidt (who was not a part of the welfare check that night). He noted these calls are common: students new to the area who prompt concerns that turn out to be nothing serious. “It was very consistent with the majority of those calls,” he said. (Protocols changed after the tragedy, and now include more records checks, including for gun purchases.)

Notably, Chin had done exactly what threat assessment hopes for above all else: She made the difficult choice to report a loved one to authorities for help. Today, in Santa Barbara and many other places, the response to such reporting would and should be quite different.

The next day Chin also called a counseling office at Santa Barbara City College to alert them to the incident but failed to connect with anyone. She felt relieved after the welfare check, though. And she knew she’d be able to see Elliot again herself in less than three weeks, when she and Georgia would head to Montecito for their favorite sushi dinner together.

in front of you, sharing what only a mother who has been through this can know.”

It was mid-August 2022, and inside the low-lit main ballroom of the Disneyland Hotel’s conference center, Chin Rodger was telling her story to an audience for the first time. In attendance at the annual training conference of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals were more than 1,000 psychologists, counselors, cops, FBI agents, and other practitioners. (The organization has convened in this rather surreal location since shortly after its founding in the early 1990s by threat assessment experts from the Los Angeles Police Department.) I’d attended this conference for several years myself, watching presentations of numerous harrowing case studies, and rarely had seen the typically stoic crowd so gripped with emotion.

“My life as I knew it ended that day,” Chin said. “Life can change in an instant.” She wept as she spoke from the podium, her voice quiet but deliberate.

“I want to share now what I saw in my son—his behavior, circumstances, and actions that culminated in this horrific tragedy—so that when you’re out there talking to parents, or to a young man on this same pathway, you’ll have more insights on your mission to prevent targeted violence.”

“Sorry,” she said, steadying herself. “I didn’t know this was going to be so hard.”

She recounted finding Elliot’s video, the welfare check, the final dinner, and many other details preceding the devastation. She said she believed firmly that the outcome would have been different if a threat assessment team had been involved “to dig deeper, ask more questions, connect all the dots.” She paused for another deep breath. “Then my son and the six individuals whose lives he took would be here today, and the families whose lives were destroyed would never have to live this nightmare.”

She said that being brought to her knees by tragedy made her want to advocate for threat assessment. “It will give me the courage to stand back up, to go forward with hope. I want to thank you all for what you are doing. I know you are saving lives,” she said, her concluding words met with a standing ovation.

After returning home, she began hearing from more leaders in the field. A senior federal agent emailed her: “As a career threat investigator, I appreciated everything that you shared with us, and everything you did to try to prevent this tragedy. As a parent, however, I was blown away by your openness and your willingness to talk so honestly about what must have been the most difficult event of your life. I doubt that there was a dry eye in the audience by the time you finished, mine included.”

Since then, Chin has spoken at additional trainings, including for school systems and corporate programs. (She declines payment, and has funded scholarships for law enforcement agents to attend.) Her talk now includes a call for broader threat assessment programs in communities.

“I feel very fortunate now in my journey to know the people who are doing this important work,” she told me. It’s a path she chose, but she also feels that a “river of grief” carried her inevitably to it.

At a recent training not far from Sandy Hook Elementary School, a young FBI analyst approached to thank her. She explained that she’d been in a class with Elliot at Santa Barbara City College and had talked with him a couple of times: “He was very shy, and so polite and kind.” She’d wished that she’d reached out to him more. She told Chin that she’d planned to go into the military, but that after the attack she grew interested in the FBI and threat assessment. Now she was helping school systems learn how to prevent tragedies.

Chin was floored. “That was a very powerful moment for me.”

On that trip, she also went with Scarlett Lewis to the Sandy Hook memorial and Jesse’s grave. “I could feel that she has forgiven, and really has grown and evolved so much,” Chin said. “I drew strength from that.”

We were sitting in a cafe on a warm LA afternoon as Chin described her own evolving struggle. “I miss Elliot very, very much,” she said. She spoke of how small things could still hit hard, like seeing his favorite oat clusters cereal at the grocery store. “The feeling of that memory overwhelms me and I have to leave. Even now that can happen.” Yet, for years she felt that she had no right even to acknowledge her own grief, out of deference to the victims’ families. “They lost their children to what he did. They had no say in that. Elliot made the decision to do what he did.”

There are ways in which she still can’t confront his violence. “I have not put myself there yet, to visualize the horrible things he did,” she said, tearing up. “It’s still just so hard.” She was quiet for a moment. “Even saying the words ‘mass shooter’ is still really hard for me. But I’m working through it.”

Shooters Paradise in 2024—an indoor gun range where Elliot practiced shooting

Philip Cheung

Though he also used knives and a car, Elliot wrote that his “main weapons” for vengeance would be guns. Like most mass shooters, he purchased them easily and legally.