Mother Jones; Steven Freeman; Duke University Press

When police kill someone, a medical examiner lists their cause of death—which plays a significant role in whether a police officer will be held accountable.

Some of those determinations shield the police from potential accountability: notably, “excited delirium,” a so-called syndrome not recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases, with research finding that most deaths attributed to the term involve aggressive restraint.

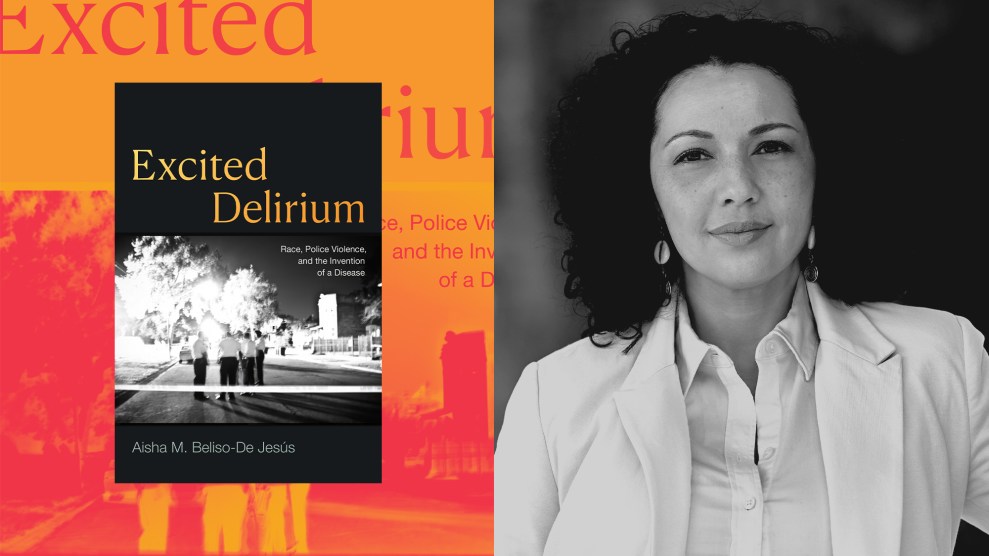

Aisha M. Beliso-De Jesús, a professor of American studies at Princeton University, traces the history of “excited delirium” in a new book, Excited Delirium: Race, Police Violence, and the Invention of a Disease—and calls it a “very useful tool that has allowed medical examiners to participate in these cover-ups.”

Beliso-De Jesús spoke to me about the racist and xenophobic views behind the term, the devastating impact of its pseudoscience on the families of the deceased, and what has to be done to move forward.

Forensic pathologist Charles Wetli first used the concept of “excited delirium” in dismissing the deaths of Black sex workers in the 1980s; they were later found to have been murdered by a serial killer. Does the term’s origin speak to its being dehumanizing?

Medical diagnoses are supposed to be helpful to people. But as we can see in the example of excited delirium, and specifically with the misdiagnosis of the cases that you’re referring to—the misdiagnosis of Black women who were strangled to death, murdered and raped by a serial killer—which Charles Wetli described as “cocaine sex deaths,” this horrific term was really used for him to substantiate his argument.

He used these Black women’s deaths to sort of make the argument that Black people, who he saw as a species that was separate from white people, had a specific genetic flaw [causing them] to die spontaneously.

He argued Black women died through small amounts of cocaine use and sexual activity, which he assumed or presumed to be consensual. Then he argued that Black men died spontaneously around police officers. This reveals so much dehumanization.

How did Wetli use and misconstrue Afro-Latine religions in rationalizing excited delirium?

The relationship between Wetli’s research on Afro-Cubans and cocaine and “excited delirium syndrome” is not direct or obvious, but I think it’s much more subtle and ingrained. So this is the 1980s, during the Mariel Boatlift, when 125,000 Cubans arrived as refugees in Miami—and those Cubans that arrive are darker, poorer and less well or less resourced than the previous generations of Cubans, who were whiter and wealthier.

Wetli was in his first couple of years as the new assistant medical examiner, and at the same time, there was a mass criminalization of this community. You see it in stereotypes like the famous Tony Montana from Scarface, who is this sweaty, aggravated, sexual predator mobster who is addicted to cocaine and murder.

Charles Wetli’s research on Afro-Cubans and cocaine, particularly on the tattoos of Afro-Cubans, is a participation in this longer criminalization of Afro-Cuban religions. He has this hobby where he claims himself as an expert on Afro-Caribbean religions, or cults, as he calls them.

He’s saying that, basically, mostly Black and Latino men have this tendency to become aggressive, sweaty, and overheated—essentially just self-combusting as a result of their aggressiveness. And as a result, he argues, they die, and police witness their deaths. It becomes a pattern with the Afro-Cubans he’s studying, where he blames the religion and the Cubans as these aggressive criminals, almost a plague infection into the United States.

How has the label of “excited delirium” in the killing of Black people by police been used to underplay how lethal other forms of police violence can be, such as the use of tasers?

Excited delirium has allowed for certain deaths to go under the radar for so long. With shootings, it’s very clear what the cause of death was. But for many years, with this term, these deaths have been completely ignored.

What excited delirium does is say that the person’s own behavior— cocaine use or hyper-masculinity, aggressiveness—leads to their death. As a result, there’s a very frightening, medicalized cover-up of police violence. If it hadn’t been for footage of George Floyd’s death, many people would have taken for granted the initial argument: that he was simply a man who died under medical distress. That was what [Minneapolis police] had posted when his death first occurred. Without the bystander video, there really would have been no way for the world to have known that this was someone who was essentially murdered in plain sight.

Was there anything that stood out to you in conversations with family members of people whose deaths were labeled as excited delirium?

For a lot of the family members I spoke with, there is a sense of relief—because for many years, people were blaming the victims. A family I interviewed was told that their father just suddenly up and died during a police car chase, that it was his drug use, and his heart had just self-combusted. There were other stories that maybe the police had pushed him off the road. Questions around that completely got erased by the narrative.

These people who are labeled as dying by “excited delirium” are often seen as written off by society, similar to the way that the Black women who were murdered and raped were written off as so-called “crack whores.” That weaponization [of the term] by police justified blaming the victims, and in many [cases], created a buffer for police and medical doctors to work together to write off whole communities.

The American Medical Association came out against “excited delirium” in 2021. What do you think would need to change for its racist pseudoscience to be discarded?

I’m really glad to see that there have been many people, many organizations, many states, actively working against excited delirium right now. I think it’s [a trend] that grew out of the post-2020 uprising of people coming together and recognizing systemic police violence.

That practice has not gone away simply because people don’t use the term any longer. People are still being tased and asphyxiated. Police officers are putting their weight on people’s bodies, putting them into chokeholds; people are complaining of not being able to breathe, and then ultimately dying. Medical examiners and coroners are still using the same kinds of medical justifications, like heart failure and drug use, rather than acknowledging the role of police violence in these deaths.

We have to continue to ensure that we don’t just focus solely on this term, but on the broader structure of policing in the country and how these two institutions—medical institutions, police institutions—are tied together.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.