It’s hard to look at these pictures of Harlow and Jean Cagwin leaving their farm and not think how lucky they are. In spite of a painful parting from land they have lived and worked on for more than seven decades, they look for all the world like fortunate survivors of a general disaster, and that is what they are. They own land close to Chicago, land that developers would pay for; they can look forward to a new farm and a new house and a fresh start. Many others have not been so lucky.

Over the last 50 years, agribusiness, farmers themselves, and the U.S. government have aggressively pursued policies that have succeeded so well in destroying the family farm and the tradition of farming in America that the interested bystander has to assume that was the point to begin with. But maybe not. Maybe it was just shortsightedness and indifference to health of the land that did it.

At any rate, Americans have always guarded their right to buy and sell their land, and do with it as they see fit. They have persisted in treating every acre as a commodity just like any other commodity, exhausting its fertility with more and more production using harsher and harsher methods, denuding it of “unprofitable” weeds and wildlife, planting fencerow to fencerow, feeding more and more livestock in ways that are less and less natural. Farming as it is done all over America is sick unto death (as the latest farm bill, in which huge subsidies went to the largest producers, continuing the decimation of the family farm-shows). Twenty years ago it was clear that most family farmers would not be replaced by their children. Even then, the average age of the American farmer was over 50. Most of their children had moved off the farm and into town, seeing no promise in the land–most farms are not profitable, for one thing.

There is an old joke in Iowa: A farmer wins a million dollars in the state lottery, and a reporter asks him what he plans to do with it. He says, “Aw, I guess I’ll just farm till it’s gone.” For another thing, farming is unrelenting hard work. Every machine or device that has been invented to relieve the work has ended up making the work more expensive and complex while divorcing the farmer from the natural world that he used to enjoy. The tractor is the first best example–farmers who bought tractors to speed up plowing, planting, and cultivation ended up having to farm more land to pay for the tractor.

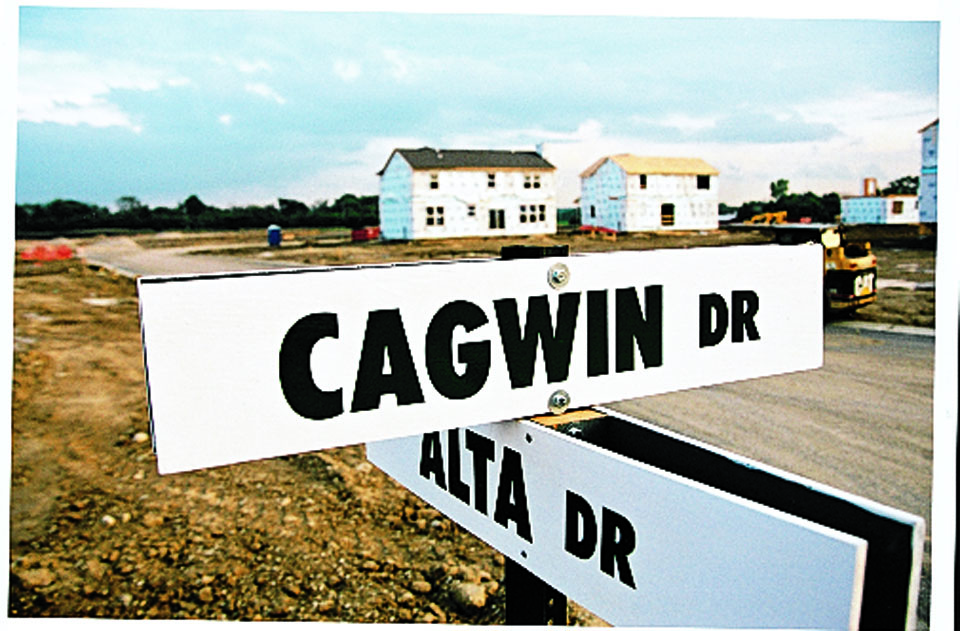

The great illusion in farming has been economy of scale, the very idea that has destroyed the farmer’s ability to pay close attention to his land, his livestock, and his crop. And it is economy of scale that has given us abundant, cheap, tasteless, and unhealthy food. There is nothing to be done about farming, and most Americans don’t care about it anyway. In California and many other states, they leave it to migrant workers. In the Midwest, they leave it to old people. In the East, they go to spectator farms, where they buy apples and pumpkins and learn to bake pies. When farm issues come up for discussion in Congress and in the media, they yawn. So the best land goes to houses. Maybe that’s okay. Perhaps the deer and the foxes and the coyotes will come back, and a few of the birds. Wildflowers and other plants that like disturbed soils will seed themselves and the city will spread out. Maybe some of those acres will support gardens and nurture future gardeners who will forget farming as we have made it over the 20th century, and try something new and better.