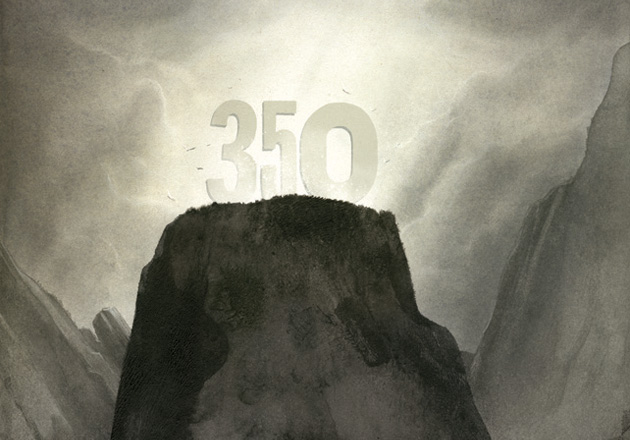

Illustration: Sam Weber

Sooner or later, you have to draw a line. We’ve spent the last 20 years in the opening scenes of what historians will one day call the Global Warming Era—the preamble to the biggest drama that humans have ever staged, the overture that hints at the themes that will follow for centuries to come. But none of the notes have resolved, none of the story lines yet come into clear view. And that’s largely because until recently we didn’t know quite where we were. From the moment in 1988 when a nasa scientist named James Hansen told Congress that burning coal and gas and oil was warming the earth, we’ve struggled to absorb this one truth: The central fact of our economic lives (the ubiquitous fossil fuel that developed the developed world) is wrecking the central fact of our physical lives (the stable climate and sea level on which civilization rests). For a while, and much longer in the US than elsewhere, we battled over whether this was true. But warm year succeeded warm year and that fight began to subside. Instead, the real question became, is this a future peril, the kind of thing you take out a reasonably priced insurance policy to guard against? Or is it the oh-my-lord crisis you drop everything else to deal with? Will Hitler be happy with the Sudetenland, or is the world going to spend every cent it has, not to mention tens of millions of lives, fighting him off? Trouble, or TROUBLE? These last 12 months, we’ve found out.

It was September 2007 that the tide began to turn. Every summer Arctic sea ice melts, and every fall it refreezes. The amount of open water has been steadily increasing for three decades, a percent or two every year—it’s been going at about the pace that the hairline recedes on a middle-aged man. It was worrisome, and scientists said all the summer ice could be gone by 2070 or so, which is an eyeblink in geologic time but an eternity in politician time. In late summer of last year, though, the melt turned into a rout—it was like those stories of people whose hair turns gray overnight. An area the size of Colorado was disappearing every week; the Northwest Passage was staying wide open all September, for the first time in history. Before long the Arctic night mercifully descended and the ice began to refreeze, but scientists were using words like “astounding.” They were recalculating—by one NASA scientist’s estimate the summer Arctic might now be free of ice by 2012. Which in politician years is “beginning of my second term.”

The key phrase, really, was “tipping point.” As in “I’d say we are reaching a tipping point or are past it for the ice. This is a strong indication that there is an amplifying mechanism here.” That’s Pål Prestrud of the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research-Oslo. Or this, from Mark Serreze, of the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado: “When the ice thins to a vulnerable state, the bottom will drop out…I think there is some evidence that we may have reached that tipping point, and the impacts will not be confined to the Arctic region.”

“Tipping point” is not, in this context, an idle buzzword. It means that the physical world is taking over the process that humans began. We poured carbon into the atmosphere, trapping excess heat; that excess heat began to melt ice. When that ice was melted, there was less white up north to reflect the sun’s rays back out to space, and more blue ocean to absorb them. Events began to feed upon themselves. And in the course of the last year, we’ve seen the same thing happening in other systems. In April, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration released a report showing that 2007 had seen a sudden and dramatic surge in the amount of methane, another heat-trapping gas, in the atmosphere. Apparently, one reason is that when we burned all that fossil fuel and began raising the temperature, we also started melting the permafrost—melting eight times more of it in some places over two decades than had thawed for the previous 1,000 years. And as that frozen soil thaws, it releases methane; enough of it now bubbles out to make “hot spots” in lakes and ponds that don’t freeze during the deepest part of the Siberian winter. The more methane, the more heat, the more methane. Wash, rinse, repeat.

The final piece of the puzzle came early this year, and again from James Hansen. Twenty years after his crucial testimony, he published a paper with several coauthors called “Target Atmospheric CO2” (.pdf). It put, finally, a number on the table—indeed it did so in the boldest of terms. “If humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted,” it said, “paleoclimate evidence and ongoing climate change suggest that CO2 will need to be reduced from its current 385 ppm to at most 350 ppm.”

Get that? Let me break it down for you. For most of the period we call human civilization, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere hovered at about 275 parts per million. Let’s call that the Genesis number, or depending on your icons, the Buddha number, the Confucius number, the Shakespeare number. Then, in the late 18th century, we started burning fossil fuel in appreciable quantities, and that number started to rise. The first time we actually measured it, in the late 1950s, it was already about 315. Now it’s at 385, and growing by more than 2 parts per million annually.

And it turns out that that’s too high. We never had a number before, so we never knew whether we’d crossed a red line. We half guessed and half hoped that the danger zone might be 450 or 550 parts per million—those were still a little ways in the distance. Therefore we could get away with thinking like the young Augustine: “Lord, make me chaste, but not yet.” Not anymore. We have been told by science that we’re already over the line.

And so we’re now in the land of tipping points. We know that we’ve passed some of them—Arctic sea ice is melting, and so is the permafrost that guards those carbon stores. But the logic of Hansen’s paper was clear. Above 350, we are at constant risk of crossing other, even worse, thresholds, the ones that govern the reliability of monsoons, the availability of water from alpine glaciers, the acidification of the ocean, and, perhaps most spectacularly, the very level of the seas. It is at least conceivable that instead of a slow, steady rise in the height of the oceans, we could see rapid melt in Greenland and the West Antarctic, where much of the world’s frozen water resides. We can’t rule out, warns Hansen, a sea level rise of up to 20 feet this century. Plug that into Google Earth and watch waterfront developments turn into high-priced reefs. We can’t rule out, in other words, the collapse of human society as we’ve known it. “If humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted…” We should add the phrase to the oath of office for every politico on the third planet.

So what does this mean? If you took 350 to be the most important number on the planet, what would it imply?

In essence, it means that we’ve got to transform the world’s economy far more quickly than we’d hoped. Almost everyone knows that this transformation is coming—that by century’s end we won’t be relying on fossil fuel, both because the oil will have run out and because the environmental damage will be intense. But the question is how quickly. The kind of change envisioned before last year was still a little leisurely—maybe the developed world cutting its carbon emissions 15 or 20 percent by 2020. That’s far more than the Bush administration or its energy-industry cronies would go for, of course—at ExxonMobil’s annual meeting last spring, ceo Rex Tillerson said he envisioned a world that still used fossil fuel for two-thirds of its power in 2030. A world where change came slowly enough that everyone could make every last penny off their sunk investments in coal mines and oil platforms. And a world where politicians didn’t need to raise the price of carbon steeply, and hence didn’t need to arouse voters.

But the 350 world looks different. We’re not worried we might have a weight problem. We’ve been to the doctor and the doctor has said, “Your cholesterol is too high. Scaring me. You’re in the danger zone. You need to change your diet and then you need to pray that you get back down where you’re supposed to be before the stroke that’s coming at you.” When that happens, you clean the cheese out of the refrigerator and go cold turkey.

In energy terms, that would look like this:

[ 1 ] No more new coal plants, because although the world still has immense amounts of coal, it’s immensely dirty. And the people who tell you about clean coal are blowing smoke—literally.

[ 2 ] A cap on the amount of carbon the country can produce—which, in essence, is a tax. America would say, just as it does now with sulfur from coal plants, “We’re only going to release so much carbon every year.” CO2 would stop being free; in fact, it would become expensive. In order to simplify the process, the upstream producer who mines, imports, or sells the fossil fuel would get the tab. ExxonMobil would have to pay dearly for a permit to release x amount of carbon, a cost it would pass on to consumers. Then those consumers would use less, and markets would go to work figuring out all the possible ways to cut demand and boost renewables.

[ 3 ] An international agreement, including China and India, to do the same thing around the world.

Now, these are three of the hardest tasks we’ve even thought about since we took on Hitler. They go to the very heart of the way our economy operates: We get most of our electricity from fossil fuels, any increase in the price of energy affects every single part of the economy, and China and India are pulling people out of poverty largely by burning cheap coal. If you’re a person who uses a lot of fossil fuel, i.e. an American, then they’re unappealing. If you’re a person who would like to use even a little energy, i.e. almost anyone in the developing world, then they’re maddening. And yet they are what the physics and chemistry of the situation dictate. So the question becomes, how to make them happen?

The logic imposed by 350 is fairly straightforward. In order to keep Americans from rebelling, we need to take the money we’re charging ExxonMobil for those pollution permits and return it to the taxpayers—everyone needs to get a check every month to, in essence, buy us all off. To help make us whole for the price rises that will inevitably come, the price rises that will do the work of wringing fossil fuel out of the economy. ExxonMobil would pay, then we’d pay—but we’d get some of the money back in the mail. We’ve got to make the switch so fast that it’s going to be brutally expensive—think $10 gas—and our democracy will never support it for long without that monthly check.

But we can’t give ourselves back all the money. Because some of it is needed to make the rest of the world whole—to build windmills for the Indians so they won’t use the same cheap coal that we used for 200 years in order to get rich. That is, we’re going to need a Marshall Plan for carbon—with the same mix of idealism and self-interest that motivated the Marshall Plan in Hitler’s wake.

We also need serious investment in infrastructure, both technological and human. For instance, concepts like concentrated solar power—those big mirror arrays in the desert—have gained real momentum in the last 18 months. Former Clinton administration energy analyst Joseph Romm recently calculated that such arrays could provide America with all of its electricity from a 92-square-mile grid in the Southwest desert—but only if promoted via loan guarantees for the entrepreneurs who build them and a new generation of transcontinental transmission lines. Meanwhile, demand is skyrocketing for small rooftop solar panels, but increasingly there’s a shortage of trained installers, which means our community colleges need money to start training them. No matter what the price of energy, homes aren’t going to insulate themselves—this is the great opening for a green-jobs revolution. (See “The Truth About Green Jobs.”)

You’ll note here I’m talking more about what we should do in the US House (and Senate) in the next year or two than which bulbs you should be changing in your house. diy conservation makes great practical sense, but we won’t save the planet that way. One by one, trying to do the right thing, we add up to…not nearly enough. You cannot make the math work that way—there are too many sockets and too many tailpipes and most of all too much inertia for voluntary action to do the trick. It didn’t work when President Bush made voluntary reduction by corporations his global warming “policy,” and it won’t work fast enough with individuals either.

Which is not to say that life at home doesn’t need to change. It does—and it will, once we’ve taken the political step of making the price of carbon reflect the damage it does to the environment. Look at what happened this past year when the price of gas finally rose far enough to get our attention. We began riding trains and buses in record numbers. Total miles driven fell, sharply, for the first time since we started keeping records in 1942. We groused and moaned and we started to change. General Motors decided to sell its Hummer factory.

If we get that check every month to cover some of the damage, it will help attenuate the very real heat-or-eat dilemma that will grip many people this coming winter, but the incentive to change will still be there. Buses and bikes. Smaller homes that are easier to heat. Solar panels, bought on the installment plan with loans paid off from the power generated on your roof. Local food (and lots more local farmers). Vacations in the neighborhood—no more jetting off for the weekend.

You can see every one of these trends in embryo already, driven by the run-up in energy prices that we’ve seen so far. The quick contraction of the airline industry. The collapse in home values in the distant suburbs, while homes along the commuter rail lines fare better. Again the question is all about pace—what will make them happen fast enough, across a wide enough swath of the planet. Al Gore set the example with his call for a 10-year conversion to noncarbon electricity. It’s at the outer edge of doable, and the outer edge is where we need to be. We’ll have plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on sale by 2010. The question is, can we have nothing else on sale by 2020? We built more than half of the interstate highway system in a decade. Would rebuilding our rail networks to a European standard be all that much harder? Can we get the price of energy up quickly enough to get markets on the task of finding a low-carbon way of life that works? And by works, I mean reverses the flow of carbon into the atmosphere. Because physics and chemistry won’t reward good intentions. Methane is seriously uninterested in compromise. Permafrost, notoriously, refuses to bargain. Even the absolute political power represented by King Canute couldn’t hold back the rising seas. Those forces will only pay attention if we can scramble back below 350.

Forcing that pace requires a new kind of politics. It requires forging a consensus that this toughest of all changes must happen. The consensus must be broad, it must come quickly, and it must encompass the whole earth—they don’t call it global warming for nothing.

The list of things on which we’ve achieved a broad and deep global consensus is pretty much limited to…Coke Is It. And that took billions of dollars and several decades, and it involved inducing people to drink sugar water. The odds against a strong global movement about anything tougher than that are low, with language barriers, religious barriers, cultural barriers. And we start from such incredibly different places—Americans use 12 times the energy of sub-Saharan Africans.

And yet we do have this one tool that at least offers the possibility, a tool that wasn’t fully there even a few years ago. The Internet—and its attendant technologies, like cell phones and texting—does link up most of the known world at this point. You can get pretty far back of beyond in most of the world, and someone in that village has a mobile.

And we have a number—350. The most important number on earth. If the Internet has a cosmic purpose, this could be it—to take that number and spread it everywhere on the planet, so that everyone, even if they knew little else about climate change, understood that it represented a kind of safety, a bulwark against the monsoon turning erratic, the sea rising over their fields, the mosquito spreading up their mountain.

I’m part of a group of people calling ourselves 350.org. Our goal is simple—to try to get people everywhere to spread that number. We’ve started finding musicians and artists, athletes and video makers, and most of all activists, the kinds of people who are working to save watersheds or babies, or to educate girls or to block dams, or any of the other thousand lovely things that won’t happen if we allow the basic physical stability of the planet to come unglued. We need a lot of noise, and we need it fast, in the scant months—14 now—before the world meets in Copenhagen next December to draw up a new climate treaty. Because one clear implication of 350 is that that treaty is our last real chance to get it right. If we don’t, then all we’ll be dealing with is the consequences. Once the ocean really starts to rise, dike building is pretty much the only project.

It’s not clear if a vocal world citizenry will be enough to beat inertia and vested interest. If 350 emerges as the clear bar for success or failure, then the odds of the international community taking effective action increase, though the odds are still long. Still, these are the lines it is our turn to speak. To be human in 2008 is to rise in defense of the planet we have known and the civilization it has spawned.