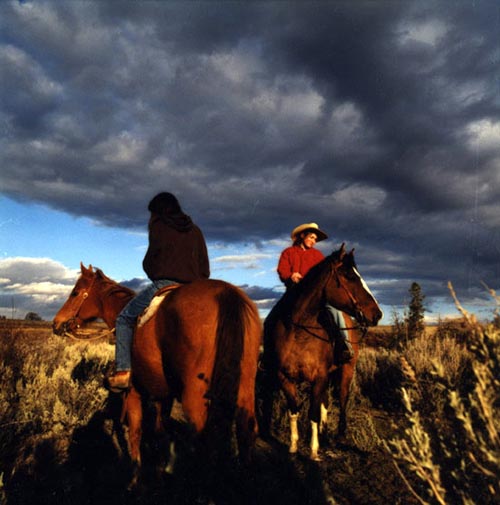

When night slides down off the mesas and settles across the sagebrush and alfalfa near the tiny western Colorado town of Silt, there are more than stars to guide llocals home. Hundreds of white lights burn in the blackness, beacons of the drill rigs that pound day and night, pulling natural gas from thousands of feet below the ocher soil. For the past several years, corporations like ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Canada-based EnCana, with the encouragement of the Bush administration and Congress, have sunk thousands of wells here in one of the most gas-rich regions of the country—90 percent of them on private land.

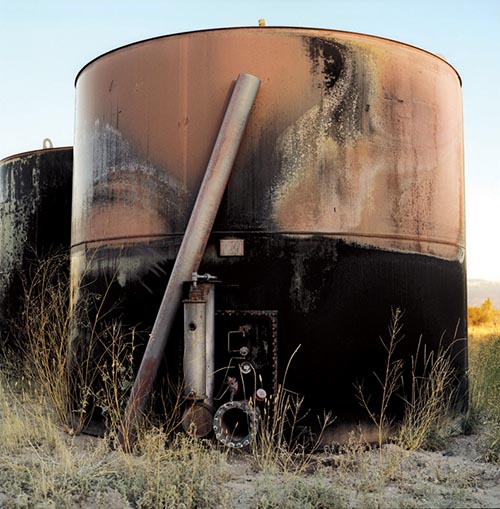

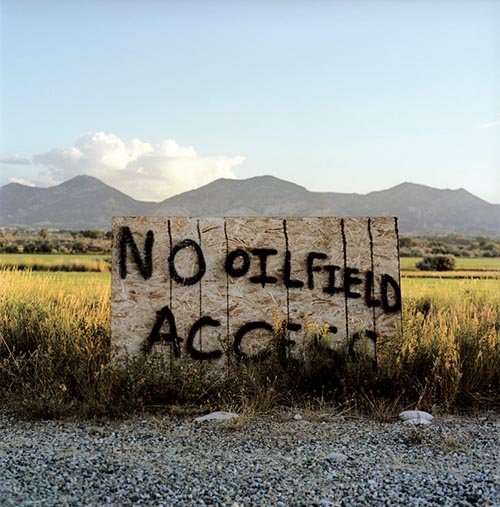

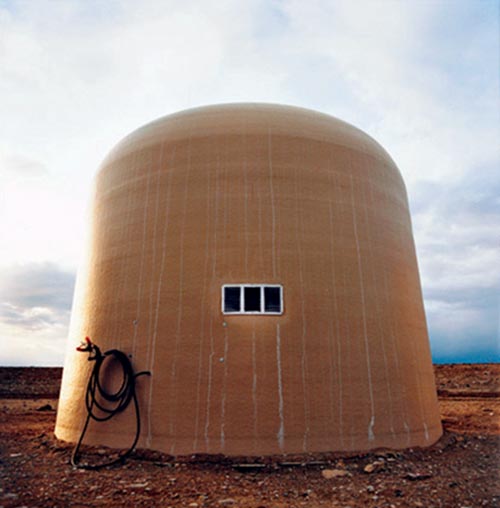

Energy companies that hold leases to underground mineral rights can cut a road and place a well pad on just about anyone’s back 40—or front yard, for that matter, since they can drill within 150 feet of a home. There are nearly 5,000 wells in Garfield County, the vast majority drilled in the past five years; gas companies plan to punch at least 7,000 more by 2015. So open pits, 100-foot-tall drill rigs, and freshly graded dirt roads carrying heavy equipment have become part of the scenery for thousands of people. And there’s more to come: Encouraged by high oil prices and new interest in natural gas (whose carbon emissions are half those of coal), gas companies are eyeing potential reserves in more than 20 states.

At a bar in Rifle, a no-frills joint with a pool table and a string of bar stools, locals down Budweiser and shots of Irish whiskey and marvel at how much the riggers make—more in a month than a guy can earn in a year of cowboying. The parking lot is full of new trucks; new restaurants on the two-block main strip serve Thai food and organic greens; and hotels are booked well into next year to house the gas workers, or “pad rats,” who’ve come from as far away as Kansas to cash in.

For some of the locals, though, the action has come at a hefty price. Ranchers and landowners describe a landscape that not only looks different, but has become downright frightening. Four years ago, a faulty well leaked benzene, a carcinogen, and methane into the creek that runs through Lisa Bracken’s property. The water fizzed like soda pop, she says, and scores of frogs and trout went belly-up. (EnCana says it’s still cleaning up the spill.) Her neighbor Steve Thompson, a machinist who moved here more than 30 years ago with his wife Patty, says the finches that frequent his bird feeders have developed visible tumors on their faces.

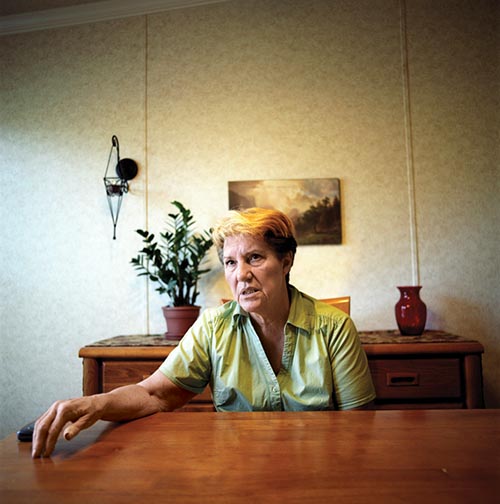

Seventy-one-year-old Dee Hoffmeister felt constantly nauseated after Bill Barrett Corp. drilled eight wells within 800 feet of her front porch in 2005; an air sample she collected and had tested revealed the presence of benzene and toluene, which can cause dizziness and tremors. (Barrett says its own tests show the air is safe.) After a holding tank near Hoffmeister’s home exploded last year, she was hospitalized for two days. The Natural Resources Defense Council has gathered dozens of similar complaints in states from Wyoming to New Mexico.

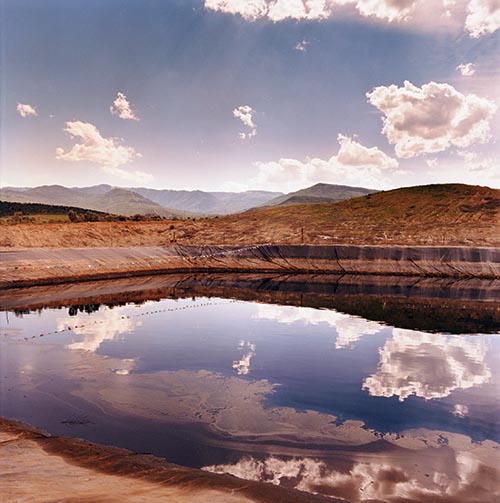

Gas may be one of the cleaner fossil fuels, but drilling for it is dirty business. When companies want to loosen underground rock in order to increase the flow, they inject a sludge of water, sand, and chemicals (the exact ingredients are considered proprietary), a process called hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking.” Up to 30 percent of the sludge remains underground, though no state or federal agency has studied its long-term effects.

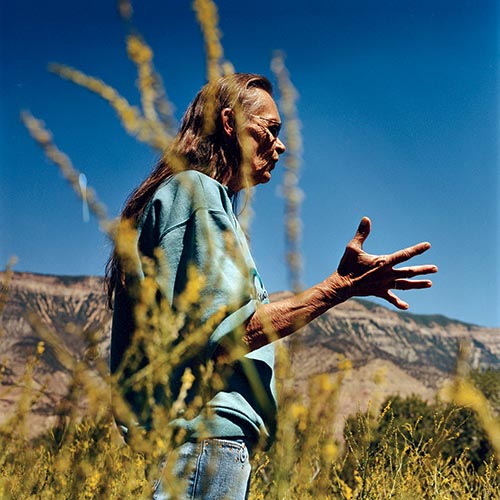

Thanks to President Bush’s 2005 energy bill, fracking is exempt from monitoring by the EPA. But the Endocrine Disruption Exchange, an environmental-health advocacy group, has spent the past several years digging for public information about chemicals shipped to the gas companies and has identified 200 likely ingredients, including arsenic and mercury; 93 percent are associated with one or more adverse health effects such as respiratory problems and brain and thyroid disorders. “I panic for the people who live over there,” says the group’s director, Theo Colborn, a birdlike 81-year-old who lives in Paonia, over the mountains from Silt.

Official evaluations of the air and water in Garfield County are hard to come by. One study, by the local Saccomanno Research Institute, found no widespread health crisis, but noted that locals suffer disproportionately from respiratory troubles. Another, conducted by the state of Colorado, warned of an elevated risk of cancer near some well sites due to the presence of benzene. Locals’ pleas for an EPA investigation have gone unheeded; an EPA spokesman in Washington says the agency “believes that the state and local authorities are taking the appropriate actions.” Wes Wilson, a senior scientist in the agency’s Denver office for more than 30 years, says the government has been “asleep at the wheel.” He adds, “When I first started here we used to solve environmental mysteries. Now we sit around and basically do nothing.”

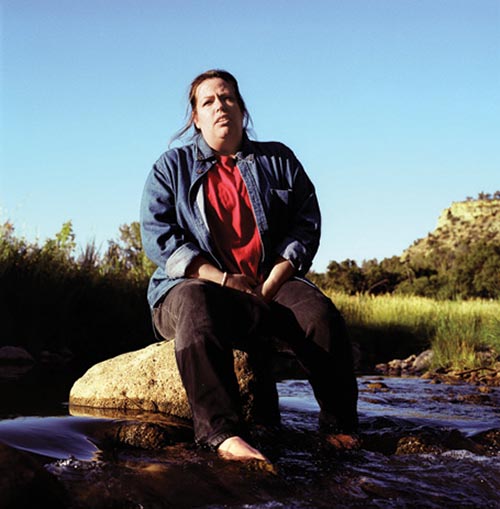

A few residents have taken matters into their own hands by filing lawsuits against the gas companies. Laura Amos, 45, a hunting guide, developed a rare tumor on her adrenal gland after EnCana dug four wells near her property in 2001. While the company drilled, she says, the cap on her water well blew off and fizzy gray liquid spewed out. The company assured her the water was fine, and she and her husband and toddler continued to drink it. Two years later Amos discovered the tumor, which is associated with a chemical called 2-BE—a substance EnCana admitted it had used in fracking the nearby wells. As part of a 2006 settlement, Amos promised to stop talking about the case; she used the money to move away.

Among the residents who’ve stayed, many have installed air filters and stopped using tap water; some even bathe their children in bottled water. “This is our home, and we don’t want to go anywhere else,” says Patty Thompson, who lives with her husband in a cabin they built themselves. Both in their 60s, they say they’ve had trouble breathing since the gas wells arrived; Steve complains of joint pain and memory trouble. One evening, as the sun dropped behind the mesas, Patty walked to a cliff on her 90-acre property with a stunning view of the rigs in the valley below. “You learn to look past the wells,” she said, “and see the beauty beyond them.”