Photo of Kogi taco by Ankoor Patel

Two weeks ago, the Culinary Institute of America held a three-day conference to celebrate what CIA president Tim Ryan called “food democracy,” which he defined as “an endless variety of great foods served quickly anywhere, anytime, at affordable prices to anyone.” For $1,095, here’s what you got—face time with Taco Bell execs and a reigning Iron Chef, a nearly limitless supply of Spanish wine and Singaporean pepper crabs, and a chance to see Ruth Reichl make top chefs cry.

About 700 people came to California’s Napa Valley for the conference, which focused on the recession’s hottest food trend. With America’s economic growth curbed, curbside has become the place to make waves in the food world. This year, the food truck manufacturer Armenco and the hot dog cart maker Kareem Cart saw their orders double. A new food truck rental company in Los Angeles, Road Stoves, has leased 30 rigs to chefs serving everything from Korean tacos to California-style dosas. “Across the country, taco trucks are no longer exceptional,” said John T. Edge, director of the Southern Foodways Alliance and the author of several food books, including Donuts: An American Passion. “They are inspirational.”

Much of the new crop of outdoor eateries’ menus are anything but humble. Whether it’s a $4 crème brûlée blowtorched in a San Francisco alleyway or a $6 Mother Trucker vegan burger from LA’s Green Truck, street food is becoming a way to indulge pre-recession tastes on post-recession budgets. New York’s pretzel and hot dog guys are now competing with niche vendors like Street Sweets and The Big Gay Ice Cream Truck. And for the adventuresome, bargains abound at black-market enterprises such as San Francisco’s Bike Basket Pies and its beloved “tamale lady.”

Some guerilla gourmets see the street food resurgence as a way to bring local, sustainable, and unfamiliar foods to a wider audience. But the scene is quickly getting crowded—and contentious. New York’s old-school vendors say they’re being pushed out by the upstarts. The newcomers complain that they’ve had their tires slashed and been threatened with sabotage or worse. Los Angeles restaurants have pushed for tighter regulations on taco trucks. And a food fight is heating up between the food-cart foodies and the restaurant chains and multinational companies that want in on the action.

The tensions were on full display at the street food conference. At its “world marketplace,” tables were arrayed with samples of fine rioja wines, some of the world’s priciest restaurants served street-food-inspired hors d’oeuvres, and attendees munched on buttery slices of ham from the nation’s only legal source of black Iberian pigs. Most tables in the marketplace were funded by agribusiness or large companies. Unilever Foodsolutions sponsored a chef who was making empanadas de camarón with Hellmann’s Mayonnaise. Earlier in the day, I ran into a Trader Joe’s executive who was seeking ideas for the store’s frozen foods section.

“This is ground zero for the commodification of street food,” griped Edge as he sampled a glass of Don Olegario Albariño. “It’s nothing but a freaking marketing trope.” Top restaurants were looking to spice up their menus, he explained, while food conglomerates wanted to figure out “how do you put this shit in a cup?”

Jonathan Gold, the Pulitzer-winning LA Weekly food critic, wasn’t surprised that the trend was already working its way up the food chain. “In a lot of ways I think food is starting to take the place in culture that rock and roll took 30 years ago, in that eating has become incredibly political,” he explained between sips of a pisco cocktail. “And just as the street has always dictated fashions on music and other things, it’s starting to happen that way in food.”

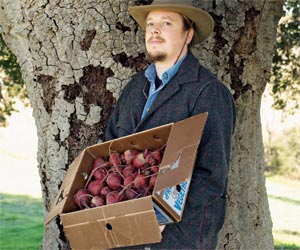

Street food’s biggest rock star is Roy Choi (left), who did a cooking demonstration before a packed audience that included PF Chang’s China Bistro founder Phillip Chiang and a representative from the food-service giant Sysco. Born in South Korea and raised in Los Angeles, Choi graduated from the CIA and became the executive chef at the Beverly Hilton. Last year, he lost his job at an Asian restaurant and on a whim started Kogi, a food truck that serves a hybrid of Mexican and Korean food. His Korean BBQ drenched in salsa, wrapped in a corn tortilla, and topped with kimchi was an instant hit. “All your joys in life come into that one bite,” he boasts of his $2 tacos. Choi’s four trucks now tweet their locations to nearly 50,000 followers and serve 5,000 people a day.

Street food’s biggest rock star is Roy Choi (left), who did a cooking demonstration before a packed audience that included PF Chang’s China Bistro founder Phillip Chiang and a representative from the food-service giant Sysco. Born in South Korea and raised in Los Angeles, Choi graduated from the CIA and became the executive chef at the Beverly Hilton. Last year, he lost his job at an Asian restaurant and on a whim started Kogi, a food truck that serves a hybrid of Mexican and Korean food. His Korean BBQ drenched in salsa, wrapped in a corn tortilla, and topped with kimchi was an instant hit. “All your joys in life come into that one bite,” he boasts of his $2 tacos. Choi’s four trucks now tweet their locations to nearly 50,000 followers and serve 5,000 people a day.

Kogi’s success has already spawned corporate copycats. Last month, the taco chain Baja Fresh acquired the Calbi Fusion Taco and Burrito Truck, a Choi imitator. Taco Bell is also flirting with a truck concept. I asked Choi if it bothered him to see big food companies swooping in on his turf. He was surprisingly unperturbed. “If fast food companies start doing this, then I hope they do it with the right spirit: with love and passion,” he said. “And if it happens that way, then I’m cool with it.” What about sit-down restaurants, such San Francisco’s Mission Street Food or Washington, DC’s G Street Food, which describe their meals “street food”? “Street food can be served in a stationary space,” Choi replied, “but your heart and spirit has to be moving.”

While Choi was assembling his tacos, chefs from Zanzibar and Brazil demonstrated “casual flavors for American menus,” current Iron Chef Masaharu Morimoto (right) was making Japanese street food, and former Chez Panisse chef Joyce Goldstein was moderating an event called “World Live Fire,” where a sword-wielding Turkish chef prepared lamb-liver kebabs. The idea of street food struck a romantic chord with some chefs at the conference. Rick Bayless, chef at Chicago’s Frontera Grill, described feeling “really conflicted” during a tour of Mexico City’s food stalls: “There seemed to be a lot more enthusiasm on the part of the chefs for the street food than for that incredible stuff that they were making for the fancy dinner that we had just served.” Suvir Saran, cofounder of Dévi, the only Indian restaurant in the country to earn a coveted Michelin star, insisted that the only place where he’d want to cook full time “is in a street cart.” The only thing stopping him, he claimed, was his business partner.

While Choi was assembling his tacos, chefs from Zanzibar and Brazil demonstrated “casual flavors for American menus,” current Iron Chef Masaharu Morimoto (right) was making Japanese street food, and former Chez Panisse chef Joyce Goldstein was moderating an event called “World Live Fire,” where a sword-wielding Turkish chef prepared lamb-liver kebabs. The idea of street food struck a romantic chord with some chefs at the conference. Rick Bayless, chef at Chicago’s Frontera Grill, described feeling “really conflicted” during a tour of Mexico City’s food stalls: “There seemed to be a lot more enthusiasm on the part of the chefs for the street food than for that incredible stuff that they were making for the fancy dinner that we had just served.” Suvir Saran, cofounder of Dévi, the only Indian restaurant in the country to earn a coveted Michelin star, insisted that the only place where he’d want to cook full time “is in a street cart.” The only thing stopping him, he claimed, was his business partner.

The allure of street food also appeals to activists who’ve been struggling to bring sustainable foods to younger and more cost-conscious eaters. In August, Bay Area chapters of Slow Food USA cosponsored the Eat Real Festival, which drew 70,000 people to eat local and organic street food. Yet Edge is skeptical that street food can bring sustainable food to the masses. In a past life he ran a sustainable-hot-dog cart that went bust, and he didn’t think hipsters hawking organic pies would make much difference. Street food “is lowest-common-denominator food,” he said. “It’s fuel on the street for real people. Organic, sustainable food is not affordable. So if you’re cooking real street food, the two don’t jive right now.”

By the end of the conference, its melting pot of constituencies was nearing the boiling point. At a wrap-up panel of 15 chefs and food writers, settling on an acceptable definition of street food proved nearly impossible. Jim Poris, a senior editor at Food Arts, said he saw street food primarily as a “delivery system for ethnic food,” a way to sell it to white diners who want “the real deal.” Ruth Reichl, former editor of the recently shuttered Gourmet, countered, “New York street food is not ethnic. Not necessarily. It’s hot dogs, it’s hamburgers, it’s—” Dévi’s Saran interjected, “Knishes?” Missing his sarcasm, Reichl went on: “It’s knishes. And in front of many businesses there are guys who make omelets on the street.”

At this point, even Choi lost his cool. His voice cracking, he launched into a story about eating in Korea. “When someone calls food ethnic…” he began, but choked up and couldn’t go on. Saran rubbed his shoulder. “We need to stop using balkanizing words like ‘ethnic,'” said Jessica Harris, the author of African Diaspora cookbooks, “because it makes everybody crazy on this side of the alley.” Afterward, Marciel Presilla, the founder of two Latin American restaurants, seemed to tap into her background as a cultural anthropologist as she talked about “colonial constructs” such as the distinction between restaurant food and street food. “Those labels bother me,” she said. “I never classify it. I call it food.”

Photos by Ankoor Patel