<a href="http://www.fairwarning.org/2010/03/old-trucks-leave-fiery-legacy-smoldering-anger/">FairWarning.org</a> / Johnson, Clifton, Larson & Schaller

Brian Taft joined the C/K death list in November 2007. As he pulled out of a parking lot near midnight in Clifton Township, Pennsylvania, his pickup was broadsided by an SUV. Taft suffered broken ribs, but that’s not what killed him, an autopsy found. Instead, it was the fireball that engulfed both vehicles when Taft’s gas tank ruptured and the pickup exploded. Burned on 99 percent of his body, Taft left a wife and two young children. (The other driver survived.)

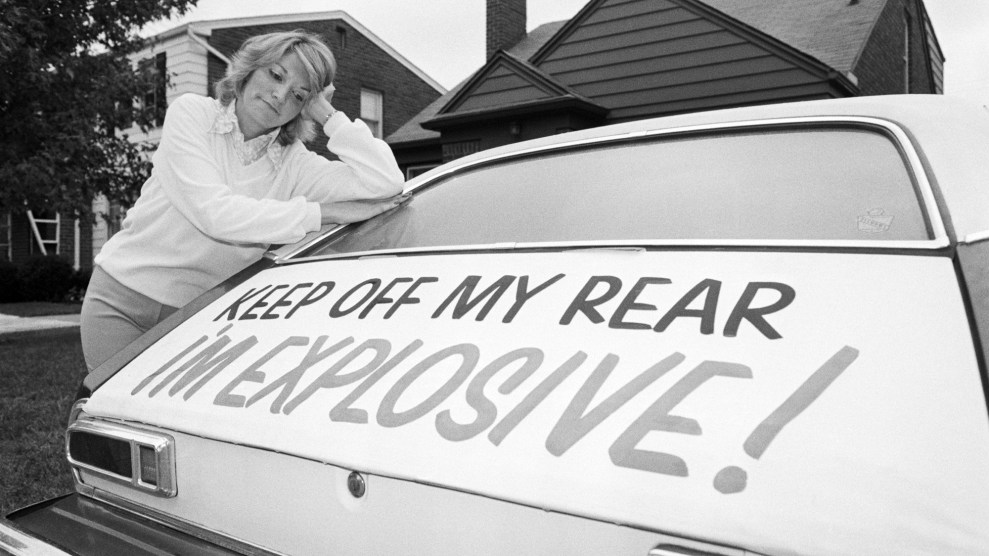

Taft, 36, was behind the wheel of a 1986 GM pickup, one of more than 9 million in the popular C/K line sold in the 1970s and ’80s. For marketing reasons, the trucks had an unusual design feature. GM wanted to offer 40 gallons of fuel capacity, but there was no place to mount a tank that big. So it offered twin 20 gallon tanks, each nearly 5 feet long, two explosive containers hanging like saddle bags outside the truck’s protective frame. Even after decades, that choice still resonates in the courts, in the lives of bereaved families and in the disfiguring scars of survivors.

Hundreds have been killed in fiery crashes of the side-saddle pickups, and many others suffered disfiguring burns. A review by FairWarning found that at least 100 people have perished by fire since federal authorities dropped an investigation that could have led to the trucks’ recall.

Sixteen years ago, a probe (pdf) by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, part of the Department of Transportation, found the risk of burning to death in side-impact crashes was much higher (pdf) in the GM trucks than in rival full-size pickups. But under intense pressure from GM and its congressional allies, transportation officials blinked, announcing a settlement in December 1994 that left millions of the trucks on the road. In exchange, GM agreed to pay $51.4 million for safety programs—things like buying child car seats for poor families—that transportation officials said would save many lives.

By that time, more than 600 people had burned to death in C/K post-collision fires. And the agreement did nothing about the remaining side-saddle pickups, described by consumer advocates and victims’ lawyers as the most dangerous vehicles, from a fire risk standpoint, ever produced.

GM officials have consistently defended the trucks, saying they have a fine overall safety record and met fuel-system safety standards when they were produced. “The safety of the trucks was established a number of years ago after extensive investigations and reviews,” said GM spokesman Tom Wilkinson. “We don’t have anything new to add.” Over the years, GM has settled hundreds of lawsuits and claims by fire victims or their families, paying out well in excess of $500 million.

Robert Lawrence of Turner, Oregon, settled his case following a fiery crash in 2005 that nearly killed him and his fianceé. Both suffered extensive burns and other injuries when a car ran a stop sign and hit the side-saddle truck in which they were riding, rupturing the fuel tank and triggering a massive fire. Five years later, Lawrence’s voice still wobbles with emotion when he talks about it. GM “knew that people were getting killed,” but “they were selling these trucks like hotcakes, so rather than stop and fix it they continued to sell them,” Lawrence said.

“Yet they make all these advertisements on TV—’The Heartbeat of America’ and ‘We care about your family,’ and all that stuff,” said Lawrence, 46. “It just freaks me out.”

Unlike Lawrence’s case, the Taft family’s lawsuit was virtually wiped out last year by the GM bankruptcy, along with hundreds of other product liability claims with a total settlement value of more than $400 million, according to a court document. With nearly all assets shifted from the “old GM” to the new company, lawyers say the Tafts and other claimants will be lucky to get 10 to 20 cents on the dollar.

Taft family members declined to be interviewed, but their lawyer Michael Gallacher said they were “angry that this vehicle was still out there.” GM knew from the start the risks of the outboard tanks, Gallacher said. “I think it’s probably the worst example of corporate negligence that you can possibly have.”

• • •

According to a federal database, following the government’s settlement with GM, the side-saddle trucks were involved in nearly 400 fatal crashes with post-collision fires through 2008. However, the database, known as the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS), attributed most deaths to the force of the collision, and only 97 to explosions or fires. But when the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration compared the database’s records on C/K pickup deaths with actual autopsies in 1994, it found that fire deaths were incorrectly attributed to crash forces more often than the other way around.

Accordingly, the estimate of at least 100 fire deaths since December 1994 seems conservative. It includes the 97 cases coded in FARS, along with 10 additional fatalities in which autopsies, police reports or witness statements reviewed by FairWarning indicated that victims survived the crash then died in the flames.

The toll has eased with the gradual disappearance of the trucks. But as they slowly wind their way to the junkyard, the tough old pickups are a reminder of how decisions by industry and government can have profound and lasting consequences.

“I still see them on the road every day,” said B.J. Kincade, an Oklahoma woman whose 29-year-old son Jimmy died in a fiery C/K wreck. “They last forever, and that’s part of the problem,” she said. “Except for the fact that they burn up, they’re not a bad truck.”

With its emergence from bankruptcy, GM could face new claims. Late last year, Megan Holt, 16, of Vicksburg, Michigan, burned to death when her ’86 side-saddle pickup veered off the road for unknown reasons and struck a tree. She survived the impact, but the truck burst into flames. Other motorists told police they heard her screams as they tried unsuccessfully to free her. An expert retained by lawyers for the Holt family has yet to inspect the truck to determine if a ruptured tank caused the deadly fire.

GM used the outside-the-frame design in its 1973-to-1987 C/K pickups, “C” denoting the two-wheel-drive and “K” the four-wheel-drive model. The trucks came with twin 20-gallon tanks or 16-gallon tanks for a shorter model. Customers could also get a single side-mounted tank. The outboard design continued in a small number of specialty trucks through 1991.

Any vehicle can leak fuel and catch fire in a sufficiently violent crash. But critics say the use of dual tanks in such a vulnerable location substantially raised the danger. Clarence Ditlow, executive director of the Center for Auto Safety in Washington, DC, which had campaigned for a C/K recall, compared the design to “taking a human heart and putting it outside the chest. The heart is protected by the ribs, and the fuel tank should be protected by the frame.”

Though GM maintained there was nothing wrong with the outboard design, a GM engineer, asked in a deposition to name a worse place for a tank, gave this blunt reply: “Well, yes. You could…put it on the front bumper.”

Before the side-saddle design, gas tanks in GM pickups rode inside the cab behind the seat, treating drivers to the sound of sloshing fuel. Moving the tanks outside the frame was seen as a safety improvement. Still, the risks of the outboard design were well-known when the side-saddle trucks were introduced, internal documents show. A 1964 GM memo (pdf) on safety improvements for the next generation of pickups stated: “The fuel tank must be mounted outside the cab and as near the center of the vehicle as practical.” A 1966 memo from rival truck maker Dodge said side-mounted tanks were “not acceptable…Any side impact would automatically encroach on this area, and the probability of tank leakage would be extremely high.”

In fact, GM engineers wanted to move the tank inside the frame long before it was finally done in 1988. One memo advised: “Moving these side tanks inboard might eliminate most of these potential leakers.” Another noted that 1977 FARS data showed a higher risk of fire-related deaths in GM pickups than in rival Ford and Dodge models. Yet another dealt with liability: “Pickup truck design is subject to intense pressure as the result of litigation due to post-crash fuel-fed fires,” the memo said. By switching to a single tank between the frame rails in 1988, “we are reducing this concern.”

With millions of the old trucks still on the road, however, the toll continued to mount. In 1992, Public Citizen and the Center for Auto Safety petitioned (pdf) NHTSA to investigate. The following year, the agency requested a voluntary recall. GM refused.

Then things came to a head. Armed with findings of the NHTSA investigation, Transportation Secretary Federico Peña (pdf) declared the C/K fuel system defective in October 1994. Among other things, investigators found the risk of burning to death in side-impact crashes was 3.4 to 6 times higher in the GM trucks than comparable Fords and Dodges.

Under federal law, the defect finding could have led to a recall. But GM furiously resisted, and even sued NHTSA. A key congressman also pitched in, going so far as to demand an investigation of Peña. Chief executives of GM, Chrysler, and Ford signed a letter to President Clinton, warning that the defect finding “threatens the entire automotive industry by creating needless, unreasonable regulatory confusion.”

A court fight could have consumed years with uncertain results. When the C/K trucks were made, they complied with the weak federal standard for fuel systems. GM would have argued in court that this meant the trucks could not be deemed defective. Seeking a graceful retreat, Peña settled.

In an interview years later with the Los Angeles Times, Peña defended his actions as necessary to avoid years of litigation. “People can criticize it to death, but there would have been nothing…[and] I would not have been at peace with myself.”

• • •

The deal did not spare GM the wrath of victims, both occupants of their trucks and those unlucky enough to hit them. When Nevada teenager Robert Bugajski was shopping for a used pickup, his parents declared the side-saddle trucks rolling firebombs and told him to pick something else. But when Bugajski, 17, was driving in May 1997, he hit a C/K truck that ran a stop sign. The tank ruptured and both vehicles exploded in flames. The two people in the C/K were incinerated on the spot. Bugajski, burned on 60 percent of his body, was pulled from his truck moaning in agony. He lingered eight days before he died.

GM settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. The company has always put the blame elsewhere—on careless driving or the violence of the crash. Indeed, most crashes do involve driver error. Brian Taft and the driver who hit him had both been drinking. Megan Holt might have nodded off before veering off the road.

But did careless design make the injuries worse? The specter of motorists surviving a crash only to become human torches is too horrific to risk the reaction of juries—so GM has almost always settled.

The number and size of settlements was kept secret from the public until 2003, when a federal judge in Montana, responding to a petition by the Los Angeles Times, unsealed an internal document over GM’s strong objections. The document showed that through August 2000, 297 lawsuits and claims were settled. “The total amount paid in settlement to date is $495,076,104,” the document said. “This yields an average of…$1,666,923 per lawsuit/claim.”

Many survivors go through life severely scarred. Art Johnson, a lawyer in Eugene, Oregon, who has represented C/K plaintiffs, said he was struck by how the “consequences of a relatively minor accident are so incredibly severe. Once you see the burn injuries of many of these victims, you never forget it.”

Days before his 19th birthday in February 2003, John Hacker was heading to his night shift at a beef jerky plant in Oregon when he nodded off behind the wheel of his side saddle truck and veered into a guardrail. The impact left him virtually unscathed, but he was horribly burned by flaming gasoline. A coworker driving behind him rolled Hacker on the pavement to put out the flames. A police report said that when the officer arrived, Hacker “was lying several yards to the south of the vehicle and was still smoldering.”

Burned on 85 percent of his body, Hacker was kept in a coma for weeks to avoid the excruciating pain. He awoke to find parts of his fingers gone. He waited some time before looking in a mirror. “I guess my heart dropped on that one,” Hacker said. “I’m a freak now,” he recalled thinking. “How are people going to look at me?”

Lingering physical effects include fragile skin that tears easily. Hacker said he has experienced a spiritual awakening that has helped him deal with the emotional scars. Spiritual faith, he said, has made “me really grateful for a lot of things I do have.”

Naturally, Hacker no longer drives a C/K truck, but plenty of others do. The exact number is uncertain, but a NHTSA document from the 1990s projected a 2010 population of 200,000 side-saddle trucks.

This story originally appeared on FairWarning.org.