Illustration: Andrew Zbihlyj

ONE OF THE hottest pieces of real estate in the San Francisco Bay Area is a 1,500-acre expanse of concrete, landfill, and asbestos-stuffed warehouses. Shuttered since 1997, the Alameda Naval Air Station occupies one-third of Alameda, an island next door to downtown Oakland known as a time warp to 1950s architecture and Kiwanis Club folksiness. For nearly a decade, the well-heeled enclave has had its eyes on the old air base, now dubbed Alameda Point. And why not? It’s smack on the eastern edge of the bay, with spectacular views of the San Francisco skyline, and just minutes from the cities to which suburbanites commute for an hour or more. It’s a developer’s dream—all the more so because building there would displace little more than a gigantic monthly flea market.

In 2007, developers announced a billion-dollar-plus plan to rebuild Alameda Point. SunCal Companies envisioned a complex featuring 1,000 detached single-family homes, 2,000 townhomes, and 1,000 condos in three-story buildings built with the latest in energy-efficient design: passive solar, geothermal heat pumps, and gray-water systems. Historic buildings would be preserved, and 25 percent of the units would be set aside as affordable housing. There would be 150 acres of parks, miles of trails, shops, and offices, and dedicated ferry and bus lines to Oakland and San Francisco. The local chapter of the Greenbelt Alliance endorsed it, calling it “the epitome of smart growth.”

Yet despite its green bona fides—and the promise of adding desperately needed affordable housing in the heart of the Bay Area—environmental activists, the local historic preservation society, and even Alameda’s mayor came out against the plan. They argued that the deal gave the developer too much power, could release toxic chemicals, and would “change the character of Alameda.” Driving his BMW past the naval base’s peeling hangars, David Howard, a 41-year-old Internet marketer and the head of Save Our City! Alameda, stressed that he’s “not anti-everything about high density.” But he felt that the Alameda Point project didn’t go far enough environmentally. Instead, he envisioned transforming the base into a “green technolopolis” that would invent a silver-bullet solution to the climate crisis. His plan didn’t include any housing, but there’d be a wind farm, a solar power plant, a factory for the electric carmaker Tesla Motors, and an “ecobranch” of the cash-strapped University of California. “It’s a wonderful location,” he concluded. “It’s a problem that needs to be solved. Why not do it here, in Alameda?”

The Alameda Point project also brushed up against a nearly 40-year-old density ban, which the Oakland Tribune has called “the ‘third rail’ of Alameda politics.” The popular measure, which effectively caps growth on the island, has helped preserve the city’s small-town feel; its population has hovered around 75,000 for decades. To get built, Alameda Point would need an exemption. When the matter was put before Alameda voters this February, an overwhelming 85 percent rejected it.

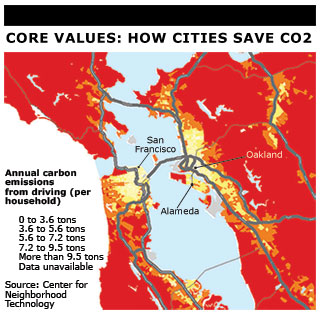

More than just another triumph of NIMBYism, the failure of Alameda Point is also a lesson in how fighting local growth can undermine the larger environmental values that many NIMBYs believe in. By 2050, the United States can expect to add as many as 200 million people. Demographers predict that they’ll require 90 million houses and 140 billion square feet of office and other nonresidential space—the equivalent of replacing all the country’s existing buildings. If we keep building in the way we do now, suburbs will gobble up a New Mexico-size amount of open space in the next 40 years. More suburbs mean more freeways and more cars, which means that by mid-century, Americans will clock 7 trillion miles per year—twice as much mileage as we do now. The alternative to this metastasizing, car-dependent sprawl is population density. And that means squeezing more people into cities and inner suburbs like Alameda. According to the Greenbelt Alliance, the Bay Area could absorb another 2 million residents by 2035 without expanding its physical footprint.

Cities are also essential to stemming climate change. As Kaid Benfield, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Smart Growth program explains, “The city is inherently energy efficient. Even the greenest household in an outlying location can’t match an ordinary household downtown.” Heating an apartment uses as much as 20 percent less energy than heating a single-family home of the same size. Promoting infill development—the practice of filling empty urban space or replacing older buildings with bigger ones—instead of building more subdivisions could effectively conserve the amount of energy produced by 2,800 power plants and could prevent some 26 trillion miles of driving. All told, if the United States focuses on increasing urban density, our greenhouse gas emissions in 2050 could be as much as 20 percent lower than they’d be in the sprawl scenario.

Yet infill development is often rejected by environmental and sustainability advocates. The chief opponent of a proposal to build taller buildings in downtown Berkeley also heads a group that urges cities “to take real action to address the causes of global warming.” The San Francisco Board of Supervisors’ hyperliberal wing recently proposed banning new high rises downtown—never mind that these mixed-use buildings would help finance a new public transit hub and a park that the same supervisors support. Last year, wealthy Seattle residents allied with an affordable-housing advocate to scuttle a plan to build new housing next to a light-rail line. Such knee-jerk NIMBYism isn’t limited to the West Coast: New York’s Long Island Pine Barrens Society is opposing a plan to build a compact, $4 billion “mini-city” on unused hospital grounds that would preserve one-third of its 460 acres as open space.

Walking the anti-density, pro-environment line can be tricky. “Our group is not the most progressive group out there in terms of promoting infill development,” concedes Kent Lewandowski, chair of the Northern Alameda County Group of the Sierra Club, which declined to support Alameda Point. “But our group does get it in terms of climate change and the impact of sprawl. It’s like we want everything. There is definitely—I won’t say hypocrisy—but there is a contradiction of sorts.”

ENVIRONMENTALISTS have long had an uneasy relationship with urban density. In what may be the first screed against infill development, Henry David Thoreau wrote, “Deliver me from a city built on the site of a more ancient city, whose materials are ruins, whose gardens are cemeteries. The soil is blanched and accursed there.” The Sierra Club was born of a desire to escape what John Muir called “the death exhalations that brood in the broad towns in which we so fondly compact ourselves,” where “we are sickly, and never come to know ourselves.” That ethos fueled the “back to the land” movement, but a less-crunchy variation of it also drove the explosion of commuter suburbs that environmentalists love to hate. A postwar ad for a New York suburb invited buyers to “escape from cities too big, too polluted, too crowded, too strident to call home.”

Determined to make cities more livable, environmentalists have promoted parks and public transit, fought freeways and factories, and portrayed developers as the ultimate bad guys. But these well-intentioned efforts to curb the Robert Moses-style excesses of urban development had unintended consequences. Strict limits on building height and attempts to squeeze ever-larger concessions from urban developers (but not suburban ones) drove up the cost of housing in many cities—sending builders and home buyers looking for open space. “It’s a situation that has unfairly favored sprawl,” says NRDC’s Benfield. SunCal developer Pat Keliher says that many of his colleagues simply avoid the cost of battling urban skeptics by building on out-of-town farmland: “It’s the old adage—cows don’t talk.”

In the early ’90s, a new movement of architects and planners known as the New Urbanism targeted sprawl by recognizing that cities should grow—but smartly and sustainably. In an effort to bridge the divide between developers and environmentalists, they replaced parking lots and tract houses with compact apartments and pedestrian-friendly streets. Yet some of the most vocal critics of sprawl have been reluctant to embrace this vision. Mike Davis, the author of City of Quartz and the Jeremiah of suburban Los Angeles, says, “What the New Urbanists tend to produce are projects that lack one of the pivotal elements of their whole philosophy—that there is no minority, or there is no economic heterogeneity, or there’s no mass transit, or there are no jobs.”

Holding infill projects to impossibly high standards is an easy way to block them. But NIMBYs’ feel-good environmental objections to development can be proxies for less politically correct fears about traffic, low-income neighbors, and falling property values, says Jeremy Madsen, executive director of the Greenbelt Alliance. In the case of Alameda Point, he adds, “That’s frankly why we wanted to come out with a strong statement of support.”

Still, some cities and states have begun to recognize that urban development—even when it’s imperfect—is inherently better than the alternative. Since 2007, California Attorney General Jerry Brown has sued or sent warnings to 45 cities for not following a law requiring them to account for their development plans’ carbon footprints. He’s forced San Bernardino County to mitigate its sprawl with green building technologies and gotten the Bay Area suburb of Pleasanton to lift a cap on new housing. In 2008, California passed a landmark law that provides incentives for municipal planners to promote climate-friendly land uses such as building apartments around transit stops. A two-tier permitting system that encourages building in more densely developed areas while increasing oversight on the suburban fringe is in use in Florida, Cape Cod, and Portland, Oregon. New York City now requires its planning commission to approve or deny new buildings in less than seven months, preventing costly, protracted showdowns.

“If true environmentalists do not reject the NIMBYs that are preventing the densification and building of cities,” says Andres Duany, the architect who designed Seaside, Florida, a project credited with launching the New Urbanism, “environmentalism itself is going to become questionable.” Ultimately, the challenge is figuring out how to address NIMBYs’ legitimate local concerns while encouraging them to see the bigger picture. “People have seen such crappy development for so many decades now that they have every right to demand that new development be as sensitive and green as possible,” says Benfield. “But I do think the opposition is often misplaced.”

By the time David Howard and I wrapped up our tour of the naval base, his green technolopolis pitch had given way to a sort of greatest hits of anti-development arguments: Alameda Point would increase crime and block views. It would displace the rabbits who live by the runway. It was racist, because increased traffic on the island would blow exhaust into minority neighborhoods on the mainland. Not to mention that the whole thing might be wiped out by a New Orleans-style deluge precipitated by our carbon-intensive lifestyle. The polar ice caps are melting, he explained, threatening low-lying areas like Alameda Point. “All the people in there—the low-income people—they’re gonna be flooded out!”