<a href="http://www.freefoto.com/preview/13-74-24?ffid=13-74-24">Freefoto.com</a>

While US climate legislation languishes, the rest of the world is already taking the next step—educating police on how to keep criminals out of the global carbon markets. In Lyon, France last month, undercover agents specializing in wildlife smuggling rubbed elbows with financial sleuths at a conference sponsored by INTERPOL intended to highlight the increasing complexity of environmental crimes and the tightening of environmental regulations in developing and developed countries. “Governments should start preparing for an onslaught of environmental court cases,” said Bakary Kante, head of the United Nations Environment Programme’s environmental law division. Some 200 officials and agents who will be investigating those cases came to Interpol’s global headquarters in Lyon from more than 30 countries for the weeklong conference to coordinate strategies to fight global environmental crime networks.

Inside the high-security INTERPOL compound, located just a block off the meandering River Rhone, the only visual reminder of “the environment” was a heap of discarded computer parts assembled like an art installation in a corner of the marble-and-stone atrium. Emile Lindemulder, a pollution crime officer with the agency’s Environmental Crime Program, assembled the e-waste pile as a reminder of one of the agency’s chief responsibilities: helping national police agencies to enforce a global treaty, the Basel Convention, that restricts the international trade in hazardous electronic waste that can contain highly toxic chemicals and minerals.

Inside, police sounded much like environmental advocates as they talked about the need to be vigilant and share intelligence about environmental abuses. “We have to prove, and prevent, murder in the future,” is how M.C. van Leeuwen, an investigator with the Netherlands National Police, described the challenge of environmental policing. Following the evidence to prove liability can be challenging, he said, and it often gets down to eco-forensics. A polluter’s fingerprints may have been laid down decades before. Front companies, foreign registries, and the like tend to obscure liability. Uncertainties surrounding the science of toxicology can make establishing cause and effect difficult.

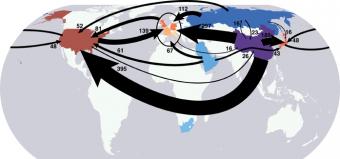

All those challenges are compounded as Lindemulder and others seek to expand Interpol’s mandate into an entirely new terrain: crime in the global carbon markets. Those markets, operating in countries subject to the emission restrictions of the Kyoto Protocol, have grown exponentially over the past five years, churning through more than $300 billion worth of transactions. “When there’s this amount of money involved,” Lindemulder commented, “criminals get interested.” Lindemulder explained that agents from traditional environmental enforcement agencies are now compelled to understand the complexities of global finance. “The carbon markets involve so many parties, so many new instruments and forms of vulnerability that we haven’t been aware of before.” (I was invited to present my findings exposing the difficulties in assessing the validity of carbon offsets, and the many uncertainties involved in turning tropical forests into carbon offsets).

The complexity of the carbon markets, which operate with ambiguous oversight, presents an array of new opportunities for fraud, noted Peter Younger, a veteran with Interpol and now in charge of the agency’s enforcement of wildlife and forest protection in Africa. “You’re talking about an international financial trade mechanism and the question is still evolving, where does the liability lie? We’re still filling in our knowledge gap.” The carbon commodities being traded, he said, are unlike any others: “You’re obtaining not a physical entity or asset but a piece of paper.” Take the rapid growth of interest in tropical forests serving as “offsets” to companies’ carbon emissions. In countries where land ownership is often disputed, the possibility for fraud is considerable, he said. “In effect, you could be falsifying ownership in something you can see in order to sell something that you can’t. And then inserting that into the carbon markets and selling it to people.”

Such a scenario is not as far-fetched as it may sound. The Overseas Anti-Corruption Unit in the City of London Police force is investigating allegations that a London-based offset developer, Carbon Harvesting Company, may have improperly claimed access to the forests of Liberia in order to sell the carbon rights to European and other companies.

In other instances, traders have generated hundreds of millions of euros in illicit profits by pocketing unpaid taxes—for instance, in a case that revealed more than 80 percent of carbon trading houses in Denmark were fronts for tax fraud.

“As the price of carbon increases, we know that the more lucrative it becomes, the more criminals will be attracted to the market,” noted the UK’s new environmental minister, Lord Chris Smith. “We need to be way ahead of the criminals in thinking about what they’re likely to do—whether trafficking in endangered species, in e-waste, or what might happen in carbon trading as it becomes an increasingly valuable commodity.”

This article was produced by the Center for Investigative Reporting as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.