Gross.Kate Sheppard/Mother Jones

I’m standing in a field next to Montana’s Yellowstone River, a gentle breeze swaying the pasture grass and tempering the 85-degree heat. White fluffs from a cottonwood tree drift slowly across the sky like cartoonish snowflakes. It would be an idyllic scene, if it weren’t for the strong smell of crude oil and the guys in hazmat suits patrolling the farm next door.

It’s two weeks to the day since ExxonMobil’s Silvertip pipeline ruptured under the Yellowstone, spilling an estimated 42,000 gallons of oil into the raging waters in Laurel, Montana. When the spill started late in the evening of July 1, the river had overflowed its banks, pushing water out into the surrounding fields. This meant that the oil, too, flowed in, and when the floods receded they left a ring of black crude around this particular field, and the thick gunk still clung to the blades of grass. Most of the damage was within 50 miles of the site of the break, though oil has been reported as far as 240 miles away.

The pair that owns the field that I’m visiting today are ranchers, a middle-aged couple that raises cattle here. They asked that I not use their names, as their lawyer advised that it could affect their claim with Exxon for the damage. I’ll call them Sarah and Jim. As we talk, cleanup workers are mowing oil-stained grass at the farm next door and shoveling oil into bags to carry away. Not long before the spill, Sarah and Jim had been talking about fencing off the field and moving their cattle in to graze; they planned to sell the hay this fall, but given the stripe of crude, now no one will be buying it. The property’s blue ranch house, usually inhabited by Sarah and Jim’s daughter, has been vacant ever since the fumes from the oil drove her to a hotel.

“I never thought about it,” says Sarah, referring to the pipeline. “I don’t know that I was even aware there was one in the river.”

A stripe of crude paints Sarah and Jim’s field. Kate Shepphard/Mother JonesThe 12-inch Silvertip pipeline is buried five feet below the riverbed, which was supposed to be far enough to prevent a spill like this from happening. It’s still unclear what caused it to leak. There has been speculation that the increased flow in the river, erosion, and fast-moving debris caused or contributed to the break. And while the company claimed that the pipeline only carried light crude, two weeks after the spill it finally confirmed that it was also used to transport tar-sands oil—which is heavier, more toxic, and more corrosive than conventional crude. Richard Opper, the director of the Montana Department of Environmental Quality, told me that Exxon and the state responders likely won’t know for sure what caused the spill until they can unearth the pipeline in September or October, when the river’s waters have subsided.

A stripe of crude paints Sarah and Jim’s field. Kate Shepphard/Mother JonesThe 12-inch Silvertip pipeline is buried five feet below the riverbed, which was supposed to be far enough to prevent a spill like this from happening. It’s still unclear what caused it to leak. There has been speculation that the increased flow in the river, erosion, and fast-moving debris caused or contributed to the break. And while the company claimed that the pipeline only carried light crude, two weeks after the spill it finally confirmed that it was also used to transport tar-sands oil—which is heavier, more toxic, and more corrosive than conventional crude. Richard Opper, the director of the Montana Department of Environmental Quality, told me that Exxon and the state responders likely won’t know for sure what caused the spill until they can unearth the pipeline in September or October, when the river’s waters have subsided.

Farther down the Yellowstone from the Silvertip spill, I meet a young woman named Alexis Bonogofsky, who runs her family’s goat farm with her partner. Bonogofsky, who is also an senior tribal lands coordinator with the National Wildlife Federation, tells me she had been eager for the floodwaters to irrigate the grazing area that her goats use in late summer and early fall. But when she got to the pasture the morning after the spill, she was surprised by the overwhelming stench of petroleum, and she could see that crude had sloshed nearly a quarter-mile into their fields. Although Bonogofsky’s farm is only 14 miles from the spill site, no one had notified her about the spill. She didn’t find out what had happened until she checked the local paper’s website.

Alexis Bonogofsky points to a pool of oily water left behind on their farm. Kate Sheppard/Mother JonesBonogofsky and her partner have found it hard to track down information about how to mitigate the oil damage on their property. The county’s emergency response office told them to call Exxon’s hotline. Exxon asked for information but had little to provide. When they finally got ahold of someone from the company, Bonogofsky said, “they told us ‘off the record’ to get our livestock away from the oil.” They were handed a brochure put out by the American Petroleum Institute, the lobbying group for the oil industry, on how to protect livestock from crude oil. Crews have come in and cut down some plants covered in oil and dropped large cloths that resemble diapers over other patches. But the water that sits in their slough is a sickly brown color, and you can still see oil sheens atop puddles in the low-lying areas.

Alexis Bonogofsky points to a pool of oily water left behind on their farm. Kate Sheppard/Mother JonesBonogofsky and her partner have found it hard to track down information about how to mitigate the oil damage on their property. The county’s emergency response office told them to call Exxon’s hotline. Exxon asked for information but had little to provide. When they finally got ahold of someone from the company, Bonogofsky said, “they told us ‘off the record’ to get our livestock away from the oil.” They were handed a brochure put out by the American Petroleum Institute, the lobbying group for the oil industry, on how to protect livestock from crude oil. Crews have come in and cut down some plants covered in oil and dropped large cloths that resemble diapers over other patches. But the water that sits in their slough is a sickly brown color, and you can still see oil sheens atop puddles in the low-lying areas.

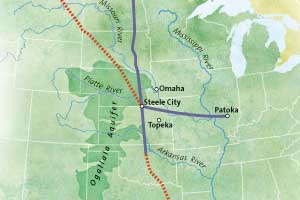

The spill came at a time when pipeline politics were already on many Montanans’ minds. Just 160 hundred miles downstream from the spill site is where the proposed Keystone XL pipeline would also cross the Yellowstone. Three times larger and many miles longer than the Silvertip, the Keystone would transport up to 21.4 million gallons of tar-sands oil every day from Alberta to Texas. It would cross more than 70 rivers and streams—including the Yellowstone—in addition to the Ogallala Aquifer, which provides nearly one-third of the groundwater used to irrigate US crops.

A recent study on the proposed pipeline found that a single spill on the Yellowstone could release up to 5.8 million gallons—140 times more than the spill earlier this month. Dena Hoff, a farmer who lives farther downstream along the river in Glendive, Montana, has been active in the debates over the Keystone XL through the regional environmental group Northern Plains Resource Council. She references the recent study as she sits with me last Saturday afternoon, taking a few minutes away from a bridal shower for her granddaughter to talk about the spill and the proposed pipeline.

Monitoring of pipelines in general is “a real joke,” says Hoff, who worries about what a spill from the Keystone XL pipeline could mean for the nearly 500 acres of farm and ranch land she owns and relies on the river to irrigate. Federal law requires fewer than half of all lines that carry liquid fuels to be inspected regularly, focusing on those that run through “high consequence” areas—or those with large populations. Federal inspectors only check those pipelines every five years, leaving the rest up to industry to maintain. “Pipeline lore holds that there are two kinds of pipelines,” Hoff says. “Those that are leaking, and those that are going to leak.”

In the wake of the spill, 70 protesters showed up at Gov. Brian Schweitzer’s office in Helena last week, demanding that he drop his support for Keystone XL. A populist Democrat with a cowboy swagger and a personality large enough for the Big Sky State, Schweitzer has lambasted Exxon for a lack of transparency. But he’s remained a staunch supporter of the new proposed pipeline. “I don’t think one ought to confuse what happens with this particular old technology, Silvertip, with what will occur in the future,” he told the energy wire Platts. “Unless people are willing to park their cars and move into a cave and live naked and eat nuts, we’re going to continue to produce energy, and that energy needs to be moved to the source of consumption.”

As we wrap up our interview, Hoff offers me some iced tea to take along for my drive back to the scene of the spill. In the very least, she says, she hopes that this spill is a reminder of what’s at stake for the Yellowstone: “It should be a national treasure, not a sacrifice river.”