Jeremy Jones on Feather Peak outside Bishop, Calif., last January. Photo by Seth Lightcap

A few years ago, Jeremy Jones was cutting up one of his favorite runs down a glacier in Chamonix, the legendary French ski area high in the Aiguilles Rouges mountains. Jones has been a regular at this spot for the last 15 years, coming for a few weeks every winter to hone the skills that have made him one of the world’s leading big mountain snowboarders. But on this occasion, he did something he doesn’t often do: stop short. The glacier, he said, had receded a few hundred yards up the valley, effectively chopping off the end of his run. “That’s kind of a drastic deal,” he told me, and not because he was bummed about losing the powder: “Glaciers aren’t supposed to move that fast.”

The experience was representative of something Jones, 36, said he’s been noticing more and more on his globe-crossing expeditions to the world’s sweetest slopes: warmer winters, less snow, and generally lame ski conditions. The culprit, he says, is climate change, and it’s not just impacting skiers and snowboarders: The $67 billion snow sport industry includes businesses near ski spots and the locals who run them, and their survival depends on robust winters. Just ask ski-area business owners from Vermont to California, who are still slogging through a major bummer of a winter this season. Climate scientists agree that global warming, unsurprisingly, is bad news for snowpack.

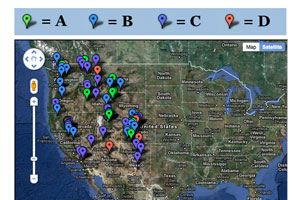

To fight back, in 2007 Jones created Protect Our Winters, a nonprofit alliance of snow athletes that raises money and lobbies politicians to pass legislation limiting greenhouse gas emissions and supporting clean energy. This fall, Jones, along with a team of scientists and other snow athletes, traveled to Washington, DC, (where the battle over climate change is “gnarly,” he said) to meet with lawmakers from snowy states, including Rep. Peter Welch (D-Vt.) and Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.). I called Jones to talk about the link between snowboarding and climate change, and the experience of swapping beanies and down jackets for a suit and tie.

Mother Jones: Is there any fundamental conflict of interest between wanting to protect the environment and having a snow sport industry?

Jeremy Jones: Yeah, that’s a pretty interesting question, but it’s an easy one to answer. Today I drove my car into town, did a bunch of errands, and went snowboarding at a trailhead on the way home. So just from snowboarding, that’s very little impact on the environment. I don’t think the problem on climate change is the guy going down the street and hopping on his local chairlift. That’s not ruining the environment. I mean, we gotta continue to live life. I’m a huge advocate of getting people outside. I think that this world in general would be a much better place with people experiencing the outdoors.

MJ: What have you tried to do to leave a smaller imprint?

JJ: As a pro snowboarder, we have a pretty damn big carbon footprint for making films, traveling the world. My biggest change has been not using helicopters. It use to be when it came time to film, that was my primary mode of transportation.

MJ: As someone who works outside for a living, you must feel a particularly compelled to protect the environment.

JJ: The snow world has been very good to me. There’s gonna be snow in the mountains for as long as, for sure my professional career, and probably my lifetime. But if you start looking at, well, are my kids gonna have the same opportunity, are my kids’ kids? A hundred years ago we had elected officials that really thought about my generation, and those elected officials put a ton of land aside as wilderness areas. It wasn’t in immediate danger, it wasn’t a jobs issue, it wasn’t a resource issue, it was strictly like, “Hey, in a hundred years there’s gonna be a kid that’s gonna really want this, and as a society we need to make sure that people can still have access to this.” You know, big props to them. We’re not doing that now.

MJ: Right. You’re talking about a responsibility on the part of lawmakers. I wonder, is there also a responsibility on the part of other snow athletes? What’s been your experience engaging them on this issue?

JJ: They’re very positive. We have a Protect Our Winters riders’ alliance, right now that’s probably 25 [professional snow athletes] deep, but that could be way bigger. I think professional skiers and snowboarders, if you asked them, “Is climate change a concern of yours, something you’d like to help solve?” probably 99 percent would say yes. It’s our backyards, it’s our playgrounds, it’s where we live our lives, and it’s in jeopardy.

MJ: You visited Washington in September to meet with members of Congress and encourage them to push for environmentally conscious legislation. What was your reception like there?

JJ: We we would target the environmental champions. Those guys, they met us with open arms saying “We really need you, you’re a key part of this equation.” And then there are other states where we have a lot of [POW] members from, and their elected officials have taken some good votes for the environment, and some bad votes. They’re not complete climate skeptics, but we need to go in and say, “Hey, this is important to your voters.” It’s tied into a lot of facets. It is a jobs issue, because, take New Hampshire for example: a ski resort closing in New Hampshire because there’s not enough snow is just as devastating as, you know, some big car manufacturer closing or what have you. And every single person in that town—from a cab driver to a ski instructor to a waiter to a bartender, you name it—everyone in town is effected financially by this. We put a lot of energy into figuring out the exact economic impact of proper winters in certain states. It’s not just sliding down a hill: in Vermont, my dad’s in the maple syrup business, a huge part of Vermont business. Other areas really depend on good runoff to fill their lakes for summer tourism.

MJ: When speaking to elected officials, what advantages does being a pro snowboarder give you? Are there disadvantages?

JJ: Well, the advantage is that I’m a little different than the traditional person they see coming through their office. Especially if they’re from these mountain regions, a ton of them are mountain enthusiasts, so there’s a connection there, for sure. And then, as far as disadvantages, well, I don’t go in there with a bunch of pro snowboarders. We bring in experts in the field, to go in with really top science. So it’s always a good reception, because certain meetings maybe I’m talking more because they really want to talk me, and certain meetings it’s our experts who are leading. We go and tell ’em, “This is what we’re seeing on the ground.”

MJ: So you encountered some mountain enthusiast Congressmen. Have you ever gone in to see an elected official, and they just want to talk shop about snowboards?

JJ: Well, no, it’s like straight to the issue, no wasting time, there’s no fluff about it. It’s more like walking out of the meeting going, “Hey, man, I spend a week a year at this hut in the Tetons,” or whatever. And it’s like, “Oh, no way,” like that kind of backburner conversation.

MJ: I was watching the trailer for your upcoming film, Further, and in the introductory voice-over you’re talking about this sensation of, when you go to the mountains, losing touch with technology and the outside world. Do you think your work as an activist has forced you back into touch with reality?

JJ: Yeah, for sure. You know, me going to Washington, I would much rather be going to a cabin in the woods. The busier I’ve gotten with Jones Snowboards and Protect Our Winters, the more important it is for me to really go away and unplug multiple times throughout the year. I’ve been in situations where I’ve had to do a two-week city tour and by the end of that I’m, it’s harder-for-me-to-breathe type deal. I become unglued for sure.

MJ: So places like Aspen, Jackson Hole, places where there tends to be robust winter sport industry, also happen to be areas where some of the big money players in the GOP tend to hang out. Do you happen to ever meet Republicans in the local ski communities that share your viewpoints?

JJ: Unfortunately, no. I think that running into a Republican who’s a climate change denier in a cabin in the backcountry would be a great chance to talk about climate change. I think that conversation would be much more levelheaded than in an office in the city.

MJ: John Muir had that attitude, I think. That it’s easier to talk about environmental issues with people when you can pull them into the woods.

JJ: Totally, and the unfortunate thing with climate is that it’s become so political. When it’s time to vote, you can be a Republican that cares about the environment but totally against major taxing or some other issue, and it’s just really a shame that it’s become such a right-wing/left-wing deal.

MJ: Would you say that the issue of climate change supersedes partisan politics?

JJ: It totally does. And there are Republicans, unfortunately, who probably would like to take certain votes a certain way, but they know what they need to get elected, and [climate legislation] comes with too much baggage and they just can’t go there. That’s definitely a big picture problem that’s going on in this country right now.