Cristin Kearns CouzensI was surprised to find myself in heels, sprinting the length of a hallway outside a Seattle hotel ballroom one day in November 2007. Attending conferences was part of my job as a dental health administrator, and I had never before felt compelled to chase down a keynote speaker. But after flipping through The Stop & Go Fast Food Nutrition Guide, the book that healthy-living guru Steven G. Aldana had handed out at the conclusion of his talk, my fight or flight response kicked in. Aldana was on his way to the airport, and I had a question for him.

Cristin Kearns CouzensI was surprised to find myself in heels, sprinting the length of a hallway outside a Seattle hotel ballroom one day in November 2007. Attending conferences was part of my job as a dental health administrator, and I had never before felt compelled to chase down a keynote speaker. But after flipping through The Stop & Go Fast Food Nutrition Guide, the book that healthy-living guru Steven G. Aldana had handed out at the conclusion of his talk, my fight or flight response kicked in. Aldana was on his way to the airport, and I had a question for him.

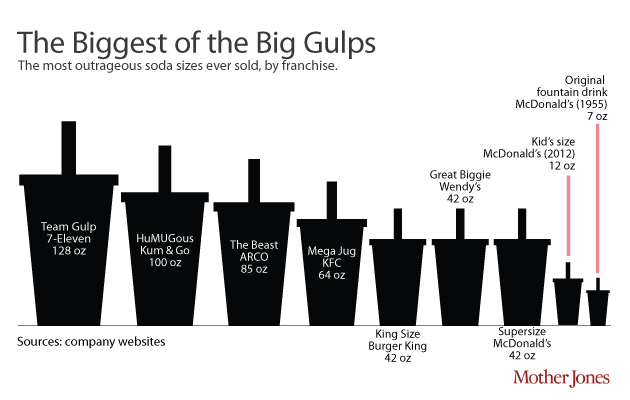

I caught him halfway up the stairs leading to the street. “How can you say sweet tea is good for you?” I blurted out, less eloquently than I had intended. Aldana’s book had given Lipton Brisk—which contains 11 teaspoons of sugars per 16-ounce can—his “You’re eating healthy!” seal of approval. Earlier in my career, working as a dental director for low-income clinics in Denver, I had seen firsthand the damage these kinds of sugary drinks incur on people’s teeth—never mind the causative role they may play in chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity.

Perched three steps above me, Aldana looked down calmly. “There is no research to support that sugar causes chronic disease,” he said. Then, before I could string another sentence together, he was out the door.

At the time I had signed up for the conference, which was meant to educate dentists about the links between diabetes and gum disease, I certainly hadn’t expected to hear leading health experts discount the role of sugar in diabetes, but that’s what happened. The other keynote speaker was Dr. Jane Kelly, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Diabetes Education Program. At her talk, Kelly distributed literature that dentists could hand out to their diabetic patients. While the handouts didn’t blatantly encourage them to drink oversweetened tea, they did manage to omit any mention of restricting dietary sugar. To control type 2 diabetes, the literature counseled, patients should lose weight and eat less fat.

The implication was that sugar is fine so long as you maintain a healthy weight. But not everyone with diabetes is overweight. To me, the advice seemed as ridiculous as telling patients prone to tooth decay that they could eat all the sugar they wanted, so long as they worked out and kept their love handles under control.

Soon afterward, inspired by Gary Taubes’ groundbreaking 2007 book Good Calories, Bad Calories (which looks at the paucity of evidence informing our federal nutrition policies) and the work of Marion Nestle (whose 2002 book Food Politics highlights the insidiousness of industry influence on those policies), I set out looking for signs that the sugar industry might be swaying the nutritional advice we give to diabetics. I already had a demanding schedule managing dental operations for Kaiser Permanente’s Dental Care Program, so I gave up TV and spent my evenings staring at Google search results instead. It took a while to hone my searches, but I eventually found enough evidence to convince me there was a story to be had. I quit my day job and dug deeper, getting away from the internet and into the musty paper archives of university libraries.

Fifteen months later, near the end of my financial rope, I tried not to get overexcited when I came across a promising reference in a library catalog of files from a bankrupt sugar company. The librarian who had archived the files wasn’t sure they contained what I was looking for; the bulk of the collection consisted of photos kept around to document the impact of the beet sugar industry on farm labor.

There in the library reading room, standing over a cardboard storage carton, I opened a folder and caught a glimpse of the first document. I sunk down in my chair and whispered “thank you” to nobody in particular. For there, below the blue letterhead of the Sugar Association, the trade group that would become the focus of our story, “Sweet Little Lies,” the word “CONFIDENTIAL” leapt off the page. I didn’t yet know what I had, but I knew I was on the right path.

A few months and hundreds of photocopies later, the pieces began to coalesce. Many of the documents were saved to give context to a photograph of two Sugar Association bigwigs accepting the prestigious Silver Anvil award from a Public Relations Society of America representative. In the years before the awards ceremony, sugar was coming to be seen as a likely culprit in diabetes and obesity. In the years to follow, sugar was portrayed as a largely innocent victim of misguided food nannies, and managed to escape regulation by the Food and Drug Administration—a public relations coup. How did this happen?

I had a host of internal memos, meeting minutes, board reports, financial statements, and clues to other archives with more documents to be investigated. But as an unemployed dental administrator, I lacked the credibility and reach to get the story to a wide audience. That’s when I decided to approach Gary, a best-selling author with the ear of the nutrition and public health communities. When my well-crafted email went unanswered I began to doubt whether what I’d discovered was as good as I thought it was. I was unsure of what to do next. Then I got a notice from my local independent bookstore, saying that Gary was coming to Denver to talk about his latest book, Why We Get Fat.

Gary has his groupies, and like me, they arrived early on that cold evening in February 2011 and stayed late. We lingered long enough that he extended an invitation to the group to join him for dinner. I jockeyed my way into a seat next to Gary, ordered my low-carb meal, and made polite conversation until the moment seemed right.

“I quit my job because of you,” I finally announced, at the risk of sounding like a stalker. But I was armed with an arsenal of facts, and Gary was all ears. He was mortified that he’d missed my email. He’d been overwhelmed with trying to draft a New York Times Magazine cover story about sugar between book-tour stops. It also turned out he was working on an upcoming book about sugar; he had promised his publisher that he would look into evidence of sugar industry influence and wasn’t sure where he was going to find it. He also knew an editor at Mother Jones who might be interested in running an article based on the documents I’d found. You can read the result right here.