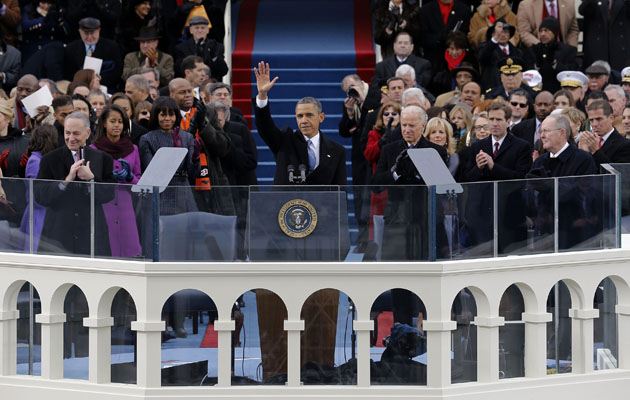

<a href="http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2011/07/11/watch-live-president-obama-holds-press-conference-today-1100-am-edt">Samantha Appleton</a>/White House photo

This story first appeared in Grist and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Some good news for congressional Republicans: The president’s threat to take unilateral action on climate isn’t looking all that threatening. White House officials are talking about small steps the administration could take, but aren’t currently pushing forward on the big executive action that advocates have wanted to see: EPA regulation of greenhouse gases from existing power plants.

During Tuesday night’s State of the Union address, the president issued a challenge to Congress to act on climate change. He pointed at previous efforts to pass market-based, cap-and-trade legislation as an example. “If Congress won’t act soon to protect future generations” from the threat of climate change, he warned, “I will.”

Prior to the speech, there was some speculation that Obama might announce support for carbon regulations on existing power plants. Last week, the EPA reported that such facilities are the primary source of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., which means new rules for the plants would be a powerful step in fighting climate change. The EPA has had the power to impose such regulations for a while, but has so far only proposed measures limiting emissions from brand-new power plants. A threat to regulate old plants, many of which have been belching out carbon and particulate pollution for decades, could be potent.

In a meeting on Wednesday morning, however, it became apparent that this isn’t going to happen any time soon—if at all. A small group of reporters from various outlets, myself included, met with several administration officials, including Nancy Sutley, chair of the White House Council on Environmental Quality; Heather Zichal, deputy assistant to the president for energy and climate; and Brian Deese, deputy director of the National Economic Council. Pressed to explain what steps Obama would take if Congress didn’t act, the response was underwhelming.

“We’re not in a position to say, ‘These are the 15 things we’re going to do,'” Zichal said, “but I think the point here is that we have demonstrated an ability to really use our existing authority—permitting-wise, what we can do through the budget—to make progress.” She noted that the administration has opened up federal land to renewable-energy development and reduced greenhouse gas emissions from the government itself. And don’t forget the work done to improve the energy efficiency of walk-in freezers and battery chargers.

Which is all fine—but it seems unlikely that Congress will feel is it forced to address the problem when faced with the prospect of Obama mandating even tighter efficiency standards for commercial appliances.

What about existing power plants, I asked? Why wasn’t that mentioned?

“The president demonstrated last night that his preference, his stated goal, is that he would welcome an opportunity to work with Congress on a bipartisan, market-based approach to reducing greenhouse gas emissions,” Zichal replied. “Whether or not that’s a reality certainly remains a question.” (No, it really doesn’t.)

Zichal repeated Obama’s commitment to the issue, and then said, “At this point in time, it would be a little premature to put the cart before the horse on existing sources, because we have yet to even finalize the proposal on new.” As for why they hadn’t finalized the standard for new power plants, Zichal noted that the EPA has been wading through more than 2 million public comments—many of which were solicited by activist groups to encourage action, not delay it. Zichal did note that many of the comments they’d received were “largely supportive.” She also said that industry had not voiced strong opposition to the standard for new plants.

Industry support, in the eyes of the administration, is key. In response to another question, Deese suggested that the choice between job creation and climate action was a false one. He noted last year’s new fuel-efficiency rules for automobiles and pointed out that automakers signed on to the policy, appreciating the certainty of a new standard.

But energy companies are not going to be anywhere near as accommodating about regulations that could shut down old coal-fired plants that have been longtime moneymakers. I asked Zichal if the administration had begun outreach to industry on standards for either new or old plants. “Not at this time,” she replied, “no.”

During both his inaugural speech and his State of the Union, Obama spoke strongly about the need to take action on the climate. But in each, he also stressed the urgency of fixing the economy. Shortly after the election, the president outlined the distinction as clearly as he ever has, absent the florid rhetoric of his more high-profile addresses.

If … we can shape an agenda that says we can create jobs, advance growth, and make a serious dent in climate change and be an international leader, I think that’s something that the American people would support.

Turning knobs and ratcheting down standards can make a difference in the climate fight, but it can’t win it. If small tweaks are the threat Obama is holding over Republicans—or if he isn’t saying what that threat might be—it’s not likely anyone will be cowed into action. When you hand someone a note reading “Do this or else,” it’s generally recommended that the recipient be afraid of the “or else.” And that there be one.