Searchers in protective suits walk through the blast zone of the fertilizer plant that exploded in West, Texas, on Thursday, April 18, 2013.Ron Jenkins/MCT/Zuma

As the news of the deadly explosion at the West Fertilizer Company plant in West, Texas, has unfolded, journalists and observers wasted no time in wondering if anyone could have seen this catastrophe coming.

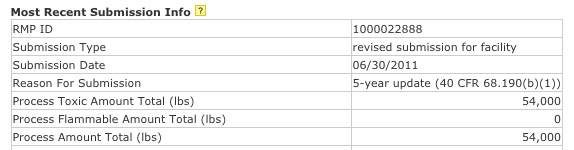

The Dallas Morning News reported that the West facility had claimed in an emergency planning report that an explosion of the kind that happened Wednesday would be virtually impossible. However, further analysis of this report shows that it contained other red flags about potential hazards and shoddy equipment. The plant’s June 2011 risk management plan (RMP), filed with the Environmental Protection Agency, identified several potential hazards, including equipment failure; toxic release; overpressure, corrosion, or overfilling of equipment; an earthquake; or a tornado.

The report asserted that the worst-case scenario for the plant “would be the release of the total contents of a storage tank released as a gas over 10 minutes.” It reported no flammable material on site, despite listing 54,000 pounds of anhydrous ammonia at the plant.

In a list of its regulated substances and thresholds, the EPA classifies anhydrous ammonia as toxic, but not flammable. OSHA considers anhydrous ammonia a flammable gas, as do the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Fire Protection Association gives anhydrous ammonia a flammability rating of 1 (0 being the lowest, 4 the highest), likely because it requires a high concentration and strong ignition source to catch fire.

It’s unclear if the EPA conducted any follow up in response to the potential hazards listed in plant’s 2011 risk report. The safety inspector listed on the report was an employee of Security Truck Services, a transporter of anhydrous ammonia located in Baytown, Texas. The EPA and Security Truck Services have not yet responded to requests for comment on the inspection process.

In response to the West explosion, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) reports that it has pursued seven investigations of the fertilizer plant since 2002, both routine and in response to complaints. The last recorded investigation occurred in 2007, 10 months after the agency dealt with an odor complaint.

The Texas Tribune notes that this probably means the facility hadn’t been inspected in the past five years. This would be consistent with a steep decline in the TCEQ’s investigations in the past few years. The agency’s last annual enforcement report showed that the number of complaints investigated has plummeted by 20 percent since 2007, though it is unclear it has been receiving fewer complaints. Its total number of investigations has fallen by more than 7 percent since 2007. Since 2008, the agency’s operating budget has been slashed by nearly 40 percent. The TCEQ has not responded to a request for comment on its investigations and whether it was familiar with the West plant’s 2011 risk report.

Turning to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration for information on the plant’s safety record turns up little. The plant’s last OSHA inspection was in 1985—not surprising considering that it would take the short-staffed agency 98 years for the agency to inspect each of the state’s workplaces. (It would take 130 years for OSHA to inspect every workplace in the United States.)