<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=coal+plant&search_group=#id=129941744&src=pXGPUhA6uVqrKrBQYNW9sA-1-14">vladimir salman</a>/Shutterstock

On Friday morning the Environmental Protection Agency released its standards for carbon emissions for new power plants, the first major milestone in President Obama’s second-term plan to fight climate change. Detractors are already describing the regulations as a job-killing “salvo” in the supposed “war on coal.” The new rules, which are the first to limit greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, could effectively stop new coal-fired plants from being built.

The standards will limit the number of pounds of carbon that can be released per unit of electricity produced, restricting gas plants bigger than 850 megawatts to 1,000 pounds per megawatt hour, and coal-fired units and gas turbines smaller than 850 megawatts to 1,100 pounds. The average new gas plant already meets these standards, but advanced new coal plants produce more than 1,600 pounds per megawatt hour, so to meet the new benchmark, they’d have to substantially cut their carbon emissions (a comparable natural gas plant clocks about 790). To do this, they’d have to use a process called “carbon capture and storage” (CCS) in which carbon is separated from emissions. And according to experts, there’s still a long way to go before that’s economically viable.

EPA chief Gina McCarthy says she doesn’t see coal dying out, and at a hearing of the House Energy and Commerce Committee on Wednesday, she defended the yet-to-be-released rules. “On the basis of the information that we see and what is out in the market today and what is being contemplated today, that CCS technology is feasible,” she said. “We believe coal will continue to represent a significant portion of the energy supply in the decades to come.”

But the skeptics aren’t buying it. “We know that CCS costs billions of dollars,” said Republican John Shimkus of Illinois at the hearing. “For these rules to be promulgated, we know we aren’t going to have any new coal-fired power plants because of the costs of CCS.” The American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity, an industry group, argues that the regulations will actually hinder carbon capture technology. “The federal government should first focus on ensuring the coal industry can economically build second-generation plants rather than put a halt to the innovative progress made to date,” said spokeswoman Laura Sheehan in a statement. “If the EPA acts as expected, the United States, which is the current global leader of carbon capture and storage…technology, will cede its ground and fall to the back of the innovation race.”

Coal is already falling behind though, and fast. “Even without CCS, the cost of a coal plant is more expensive than building a natural gas plant, given the low price of gas,” says Howard Herzog, a senior research engineer at the MIT Energy Initiative. “People who have access to gas, they’re going to build gas. This will make the economics even worse.” For coal to compete with natural gas, Herzog says, the price of gas would have to have top $10 per million BTU—roughly three times the current price.

“The natural gas boom is what changed the economics and is doing it to coal. It’s not the EPA,” says David Doniger, the policy director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Climate and Clean Air program and former director of climate change policy at the EPA during the Clinton administration. “Power companies are basically agnostic about which power source they’re using.”

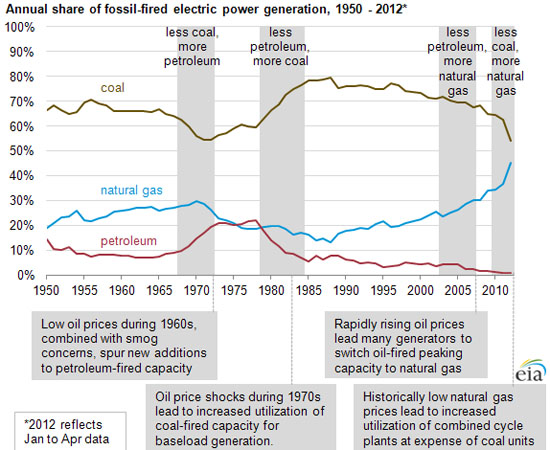

Coal’s dominance of the American energy market, which it has securely held for over 60 years, was most recently cemented in the 1970s, when the Powerplant and Industrial Fuel Use Act curtailed the construction of oil- and gas-fired plants after the 1973 oil crisis. But coal’s market share has been gently declining since those restrictions were lifted in 1987—a trend which has rapidly accelerated in recent years with the glut of newly-cheap, domestic natural gas. According to the US Energy Information Administration, “between 2000 and 2012, natural gas generating capacity grew by 96%. By contrast, additions to coal capacity were relatively minor during that period, and petroleum-fired capacity declined by 12%.” In 2012, coal power accounted for 37 percent of total US electricity generation, and natural gas accounted for 30.

The new rules will only apply to new power plants. Carbon regulations for existing plants will be proposed in June 2014 and finalized the following year. But older coal plants are already being squeezed by new EPA standards for mercury, arsenic, and other toxins, which go into effect in 2016, according to Faith Bugel, a senior attorney with the Environmental Law & Policy Center in Chicago.

If coal is being targeted, it’s not completely without reason. In a recent study that identified the 100 power plants that produced the most carbon in the US, 98 were coal plants. Forty percent of the country’s carbon emissions currently come from power plants, with coal plants accounting for more than half.

On Thursday, Mitch McConnell took to the Senate floor to denounce the forthcoming rules. “It’s just the latest administration salvo in its never ending war on coal—a war against the very people who provide power and energy for our country,” he said. “Congress cannot sit idly by and let the EPA destroy a vital source of energy and a vital source of employment.”

But the NRDC’s Doniger argues that coal’s problems go far beyond the regulations. “They’re economic losers who want to blame the EPA for their lack of competitiveness in the marketplace,” he says. “If I’m tying to bench press 400 pounds and I can’t do it, it doesn’t matter if I’m trying to bench press 425.”

Coal power isn’t likely to disappear anytime soon, however. And while Friday’s standards may stop new coal-fired plants from being built, the rules for existing plants—which will be proposed next summer—might have a bigger impact. “If you’re really going to impact climate change, you’ve got to significantly reduce the carbon you’re producing,” says Herzog, which means that “the systems that produce our electricity in the future have to produce an order of magnitude less carbon.” Still, he says, “what we’re doing here is a good first step.”

*This article was updated to reflect the numbers released by the EPA Friday morning.