roibu/iStock

One morning in October 1996, veterinary pathologist and virologist Peter Doherty was awakened by a 4:30 a.m. telephone call. “Something’s gone wrong,” was his first thought. Doherty was living in Memphis at the time, and figured one of his Australian relatives was calling with bad news. His wife picked up, and the caller said he was from the Nobel Foundation. “I’d always wondered how you know it’s not a fake, because you’ve got people in the lab who are perfectly capable of doing that,” Doherty says.

It was no prank. Doherty and his collaborator, the Swiss scientist Rolf Zinkernagel, had won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work showing how the T cells of the immune system recognize virus-infected cells. “He told us, ‘Look, you’ve got five minutes to alert people, because after that your phone’s just going to go mad, because we’re making the official announcement,'” Doherty recalls. “So we did that. And then the whole thing went crazy.” The following year, he was named “Australian of the Year.”

An animated 72-year-old with an impish grin, Doherty doesn’t do as much lab work as he once did, but he’s been prolific in other ways. I met him for lunch in San Francisco, where he’d come to give a lecture and promote two new books. Released in late-August, Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know is precisely what it sounds like—a question-and-answer primer on the pathogens that inhabit our nightmares. Even more recent is Their Fate Is Our Fate, which focuses on what birds can tell us about threats to our health—including disease and climate change. Over Asian food (he got the bi bim bap), Doherty explained how killing vultures can come back to haunt you, the reason you should never kiss a pig, and why—though he is fascinated by birds—he’s no “twitcher.”

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Your bird book kicks off with some comparative physiology. You explain why Daedalus and Icarus never would have gotten off the ground. But suppose we had a bird’s lower body density and some nicely engineered wings. Could humans then fly?

I think you’d have to be the same size as a bird, too. The biggest birds would be an albatross or a condor, and the body mass is not that big, so that must be the limit that a bird can lift. I don’t know how big archaeopteryx was—some things are gliders, so if archaeopteryx was a glider… We can fly if we use a pedal system! But not that far.

I take it you’ve become a bit of a birder.

Not really. But I’ve become much more attuned to birds. I’m an old guy. I’m a typical scientist. I’m obsessive. But as you get older, you tend to smell the flowers more. We bought a house down on the southern tip of the Australian mainland, on Bass Strait, before you cross over to Tasmania. Walking on the beach there, I got interested in identifying the birds, but I’m not a twitcher—I don’t want to identify 1,000 different species in one year. I’m just as fascinated, really, by a seagull as by a bald eagle, because of what they do and how they do it. I’m just intrigued by their physiology and their bird-ness.

What can birds tell us about the effects of climate change?

First of all, a lot of species of birds are way down in number. And a number of the species that migrate to and from the equator are tending to move their home range northward. The birds that are really endangered are the ones that don’t migrate. Their habitat is changing and they’re not necessarily going to cope because it’s happening so quickly and they don’t necessarily have time for adaptation.

You write about how drought caused by climate change can contribute to the spread of influenza in wild birds. Why is that?

It brings birds together on a limited water source, so there’s much more of a chance of transmission. Interestingly, with West Nile, 2012 was a very bad year, and that was a drought year—all the birds were coming very close together, and the insects were there, and were breeding down in the sewers in cities. It’s paradoxical: In a wild situation where you get a lot of rain and a lot mosquitos you’d expect a lot of transmission. But in an urban environment, a drought situation can give you the ideal means of transmission.

Malaria used to be endemic in North America, but we’ve managed to mostly eradicate it. Lately, we’re seeing a few cases of dengue fever down in Florida. Do you think climate change could bring about a resurgence of these sorts of diseases?

Well, it’s really a matter of mosquito control. Some people make a lot of this. And its certainly true that the range of viruses may change. We may see, for instance, Japanese encephalitis virus coming down into northern Australia, which we haven’t seen. But even way back, yellow fever, a mosquito-borne infection, used to get right up to Montreal, the St. Lawrence waterway. So you know, it’s a matter of degree. Really these viruses can still be controlled by mosquito control.

So it’s more of a problem for poor countries?

Yeah, because they can’t afford the mosquito-control measures, and because once we outlawed DDT because the effect it was having on bird eggs, it made it extremely difficult.

In the book, you had a great example showing how upsetting the natural balance comes back to haunt us—where diclofenac, a drug used on cows in India, caused a big die-off of vultures that fed on the carcasses.

Diclofenac is perfectly fine in us and in cattle, but it kills the vulture kidney, so something like 95 percent-plus of the Indian vultures have gone. The vultures are the primary bird that clears dead animals, and cattle are just allowed to die because of the sacred cow thing. The vultures strip them. When the vultures are not there, dogs strip them. That increases the number of wild dogs, which increases the amount of rabies. The first year this happened, they were getting something like 50,000 excess human rabies deaths due to dog bite. It was a disaster.

What are sentinel chickens?

Sentinel chickens are the domestic chickens that public health people park around the countryside in small flocks. These are there to detect viruses and the spread of viruses that are transmitted by mosquitoes. West Nile is one of them. The chicken recovers and makes antibodies, and so, by regularly bleeding these chickens, you can say that that virus is spreading in that region. It’s a long-used technique.

You write that scientists actually have produced transgenic chickens that are less susceptible to bird flu. Is that a viable strategy?

I think it is, but you’ll have to get people accustomed to the idea that they’re going to be eating GM chickens. And that’s the main problem.

What pathogens keep you up at night?

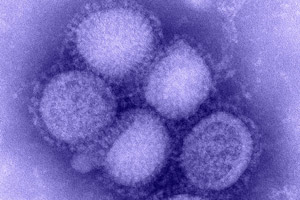

Flu is the most dangerous because it changes all the time and we can get completely new strains coming in from nature that we haven’t seen before, like the H7N9 one they’re very concerned about in China at the moment. When we’re infected, initially we don’t feel sick, but we’re coughing up a lot of virus. And so we travel with influenza. It gets around by people traveling to various places, but it doesn’t spread much in the plane.

Phew!

You’re at risk if you’re two or three rows from someone who’s coughing and spluttering flu, but it doesn’t go through the plane’s air-handling system, so it’s not dangerous in that sense. But it gets around the world very, very fast. The terrible 1918-1919 pandemic that killed 50 to 100 million people was killing people in the trenches in 1918 but didn’t get to Australia till 1919 because everyone’s traveling by ship. The 2009 swine flu was probably in Australia before it was even detected in the United States—and that’s air travel.

With flu, it seems like there’s kind of a balancing act between deadliness and transmissibility.

It’s pure Darwinian selection. The H7N9 in China at the moment is going from birds to humans. The worry would be if that virus changes and starts to transmit between humans, because it’s killing about 20 percent of the people it infects. Now of course, if it changes, it doesn’t mean it will still be as virulent.

So the same mutation that allows it to spread between humans might make it weaker?

Yeah, it could be. And the more severe it is, in a way the less dangerous it is, because the public health people will drop on it in a big way. The really dangerous flu virus is the one that, like the 1918 virus, kills maybe 2 percent. Because it’ll slip by much more readily. That’s why viruses like ebola haven’t been a problem [in the developed world]—even though they’re terrible infections.

How is it that a particular flu strain can infect one mammalian species but not another?

It can be due to the surface receptors. Flu has only eight genes, and we still don’t really understand a lot of the reasons why it infects this species but not that species, and spreads in this species, not that. There are different genes within the virus itself that seem to be important, and it may be combinations of genes. They’re simple viruses, but they’re incredibly able to defeat us in various ways.

Cats are vulnerable to bird flu, right?

The H5N1 bird flu was causing a lot of disease in big cats like leopards that were fed infected chicken carcasses. It killed a lot of leopards in the Singapore zoo, for instance, before they realized what was happening.

As a bird enthusiast, how do you feel about domestic cats?

Domestic cats should really be declawed if you’re keeping them, and the feral cats should be shot. They’re just a disaster. They’re a total disaster in Australia.

But they’re not a worry in terms of spreading disease?

There’s no known case that I know of where a cat has transmitted a flu virus to a human. So as long as the cats aren’t killing birds, you don’t have worry about it—except toxoplasmosis if you’re pregnant, but otherwise cats aren’t a big problem.

But pigs can act as mixing vessels for different strains of influenza?

Pigs are our main worry. The flu virus genetic material is organized in eight quite separate bits. So if the one cell in, say, a pig lung, gets infected with two different flu viruses, they can just repackage so you get bits of the different packages in new viruses. It’s what we call a reassortment of gene segments. That’s what happed with the 2009 swine flu. There was an American swine flu virus and there was a Eurasian swine flu. Somehow they got together, and that repackaged virus was extremely infectious for humans. The 1968 Hong Kong flu came about when a virus circulating in humans called H2N2 reassorted with an H3N8 virus that was in ducks. And that we think probably happened in a pig—we’re not sure.

Have Asian countries been forthcoming about outbreaks?

There was a holding back initially with SARS in 2002, but I think that they learned that that doesn’t really work very well, and they’ve been much more open. They haven’t been as open about what’s been happening in animals as they have been about what’s happening in humans. They also, early on, used animal vaccines they shouldn’t have used. They should’ve slaughtered to get rid of the infection in chickens, and these vaccines probably made the problem worse.

Yeah, I was actually going to bring up the economic consequences of the slaughter.

It’s a real loss. If a poor farmer has to slaughter all his chickens, maybe his kids can’t go to school.

How would a major pandemic affect the economy of a country like the United States?

People would stop flying, for a start. That means the hotel industry and the airline industry would go down the tube.

And dining. And entertainment.

Anything where people gather together. That’s what happened with SARS—I think the loss is calculated at around $50 billion, and that only affected a few East Asian areas and Toronto. I think Singapore has calculated it took a $20 billion hit. Hong Kong, similar. The calculated loss of a severe flu pandemic is $300 billion, something like that. I mean, it’s a lot of money.

America’s most popular cable reality show right now is called “Duck Dynasty,” which involves a bunch of duck hunters. Should hunters, and people who raise ducks, be worried about influenza?

I don’t think so. These species crossovers are pretty rare—but they do happen. We had a H3N2 virus last year coming across from pigs to humans at agricultural fairs. It was only people who were getting very friendly with pigs, you know, they were going up close to the pigs and saying, “How are you, pig?” sort of thing.

So don’t kiss your pig!

There’s a picture of a kid kissing a pig that all the flu guys show! Yeah, don’t kiss your pig and don’t get too friendly with a pig. Keep your distance. But the H3N2 didn’t go between humans. It only went pig to human.

Does cooking an infected bird kill off the virus?

Absolutely. It doesn’t take much to kill flu. It’s pretty labile. But it survives well in water. I don’t know any case where anyone caught flu by water, though. As far as we all know, flu only spreads by respiratory routes, by hand and nose. My Pandemics book argues that one of the best things you can do in any situation is to wash your hands and not touch your hand to your face. We all touch our hands to our face an enormous amount and we don’t realize it.

Backyard chickens are a huge trend in the United States. Are they vulnerable?

They could be, but it’s unlikely. There are chicken flu viruses that sometimes mutate, and single amino acid change can cause a completely nonvirulent flu virus to be terribly lethal. You get these outbreaks occasionally in chicken houses, but not one of them has ever jumped across into humans.

What are some scary viruses most of us won’t have heard of?

Well, the scariest in terms of the horrible-ness of the disease are the hemorrhagic fever viruses, and there are a lot of them in South America. There’s the bat viruses hendra and nipah viruses in southeast Asia. There’s a whole lot of really horrible, scary viruses, and some authors make a lot of this because they’re writing for dramatic effect. But until those viruses change to spread readily by respiratory infection, or maybe by gastrointestinal tract like the noroviruses, they’re not really a big concern.

Could we handle something like the 1918 virus?

We’re incredibly better at monitoring it and reacting quickly. There’s a great global network of influenza centers, and the technology is infinitely better. A lot of people in 1918 probably died from secondary bacterial infections. We’ve got antibiotics to deal with bacteria, and so we’d do better there. Also, it looks as though we’ll be able to make a lot of flu vaccine very fast. At the moment, it takes us at least six months to get much out there.

What’s changed?

They’ve got some of it working now in recombinant DNA technology, which means we can grow the proteins in bacteria—which means you can use every fermenter on the planet. At the moment we’re growing them in hens eggs. That’s really limiting because there’s a limited number of facilities. Our armamentarium is improving very fast. You know there’s always a chance of some weird virus that comes in from nowhere, like the one in Contagion. But so far, no.

Speaking of that, what’s the best pandemic movie you’ve ever seen?

Contagion, by far. It got a couple of things a bit wrong, but the director was Steven Soderbergh, and he’s a serious guy, evidently. He took a lot of notice of Ian Lipkin, who was the scientific advisor. On the whole, the science was great. There were various elements of dramatic effect—they seem to have three people working on this thing that’s killing half the world!

So, I gather ferrets are used in the lab to model flu transmissibility in humans…

The first human flu virus was isolated in ferrets! It was in London in 1933, I think. Some people there were working with ferrets and they bred a lot more than they wanted and they said, “Oh, does anyone want these ferrets?” And so the flu guys said, “Oh, okay, we’ll try it,” and they dropped some flu down the ferrets’ noses and they got the flu! And not only that, the ferrets infected one of the young investigators. The guys who discovered the virus were all knighted—they were all made “sir.”

Research teams in Wisconsin and the Netherlands recently engineered an unusually deadly bird flu virus that could spread among ferrets, and so presumably humans.

We’ve been doing that sort of infection in virus labs for about a hundred years. I think it was seized on for some reason. These people were working under extraordinary security conditions, they were actually top-level people. They’ve tightened the security regulations, but the real concern is not these guys doing it—the real concern is a bunch of cowboys doing it in some other country, without any control. This is not rocket science. Anyone with a basic training in molecular virology can do these experiments. People can do it in their garage if they were sophisticated and they had a bit of money.

Are there some results you think shouldn’t be published?

They ended up publishing them after a lot of controversy and discussion. The papers are in Science and Nature. But we published the sequence of the resurrected 1918 virus with very little controversy around 2000, I think it was. Nobody made much fuss and it’s a deadly virus—anyone could’ve rebuilt that virus.

And that doesn’t worry you?

There’s nothing you can do about it really. Do you want to keep it secret? Can you keep it secret? I’m not sure you can.

You could limit it to professional flu researchers.

It wouldn’t stay tight. Do you know anything that stays secret in the US? The reason I never believed conspiracy theories in the United States is because nobody can shut up!

Some of your own countrymen, in Canberra, inadvertently created a killer mouse pox virus a while back, and then alerted the world about it.

Yeah, it was an odd experiment where they put one of the cytokine genes into the mouse pox and it became extremely virulent. Look, if I was Saddam Hussein and I really wanted to make a virulent flu virus, I would take a recently drawn flu virus, I would passage it through groups of 20 prisoners, I’d take the virus from the ones who were dying, and I would passage it through more. Anyone could do this. It’s a snip, really. You just have to be unscrupulous enough.

Are you worried about bioterrorism?

I just think it’s such a lousy weapon. The best bioterror weapon is probably anthrax. We saw how effective it is: It didn’t kill very many people, but it created enormous fear and enormous disruption. But microorganisms as weapons of war are extremely poor weapons. They’re very untargeted, for a start, and not very efficient to deliver.

So you seem pretty upbeat about our being able to handle a pandemic.

We should be very careful about cutting public health monitoring and services. We should protect organizations like CDC and public health offices, and that part of the World Health Organization that deals with pandemics. There could be a lot more money put in to things like developing new antibiotics against tuberculosis and drug-resistant bacteria. I think I read something that 20,000 to 30,000 people died last year in the United States from drug-resistant bacteria. But I don’t think we should walk around in fear that some terrible pandemic is going to kill us all off. When the plague was circulating in Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries, it would kill a half to a third of the population of cities. We’ve never seen anything like that. It did have some important effects, but it certainly didn’t kill off humanity.