If you lived near Chernobyl or Fukushima, would you stay?

On April 26, 1986, an explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant changed history, sending radiation and political shockwaves across Europe. Radioactive fallout contaminated 56,700 square miles of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia, a region larger than New York state.

A generation later in Japan, on March 11, 2011, the Tohoku earthquake and the tsunami it triggered brought on multiple nuclear meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. In the initial fires, Fukushima released ten to thirty percent as much radiation as Chernobyl, contaminating some 4,500 square miles of Japan—nearly the area of Connecticut. Radioactive water continues to leak from the Fukushima plant to this day.

To the world, Chernobyl and Fukushima seem like dangerous places, but for the people who live there, that danger is simply a fact of life.

In my photography, I explore the human consequences of environmental contamination. I am interested in questions about home: how do people cope when their homeland changes irreversibly? Why do so many stay?

In the popular imagination, the Chernobyl region is a wasteland—forsaken, hazardous, and inaccessible. And yet, a generation later, life continues across these radiation-affected lands. Six million people still live here. After the accident, 188 nearby towns and villages were evacuated. Many were bulldozed, some were simply abandoned. The Soviet military created the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone to prevent public access to highly contaminated areas. Beyond this first “zone of alienation” are three further zones where radiation fell but evacuation was merely encouraged, not mandatory. In Ukraine, these three zones include 2,293 villages with 1.6 million inhabitants.

It’s been three years since the Fukushima disaster. When the earthquake and tsunami hit and caused the nuclear fallout, I knew I would eventually go to Fukushima. Last year, I started a new documentary project there. Wary of becoming another helicopter journalist, I tried hard to find a few typical people and stick with them long enough to witness their stories unfolding. Currently, about 82,700 people remain evacuated from Fukushima’s exclusion zone. Many expect they’ll be allowed to return home eventually. Generally, older residents of Fukushima Prefecture are eager to go back to their villages while younger generations are more willing to resettle elsewhere.

In Fukushima, the experience of radiation is new—at least for anyone under 70—and the impulse is to flee. For many, the search for safer ground has now shifted to worry that no ground is safe; the Japanese will have no choice but to learn, like the Ukrainians, to abide that anxiety. Why do people stay? A lack of alternatives. A sense of duty. Deep ties to the land. Decent jobs. Because this is home.

If you lived here, would you stay?

After midnight, Nina Dubrovskaya and Lena Priyenko walk two miles home to their quiet village of Sukachi from the nearest town, Ivankiv. The women, both divorcees, went in search of company but found all four of the town’s bars empty. “When the money gets short, people just get drunk at home,” says Nina.

Mie Nagai volunteers with the Japan Cat Network in the Fukushima exclusion zone. Volunteers from the group drive in each week to feed pets left behind.

A map of Fukushima hangs in the Koriyama Baptist Church. Nails and string link photos of friends of the church to the locations of their old homes. Japanese-American pastor Nobumasa Tajima and his wife, Beverly, lead weekly trips to shelters still housing evacuees. “We bring people food. But they don’t need food. They need comfort,” he says.

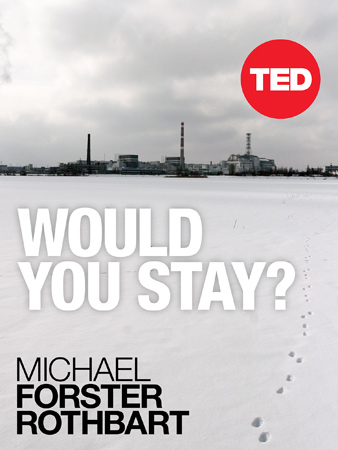

For workers arriving by train, this is the first view of the sprawling Chernobyl nuclear power plant, across the cooling pond. The plant’s heating operation has the only active smokestack. At right is the hulking shelter object, which covers the ruined fourth-block reactor.

The mural in St. Ilinsky church in Chernobyl town is reproduced at the Chernobyl Museum in Kyiv. The angel’s gaze warns humanity “about the possibility of life disappearing from the face of the earth,” says the museum director, referring to prophecies that the nuclear disaster was a sign of the apocalypse. Meanwhile, the Krynychanka (Water Spring) women’s ensemble keeps local folk music alive.

Yasuko Hamabata lives in Tokyo, but for a year and a half she has worried about her exposure to radiation. During a trip to Fukushima city, she goes to the Citizens’ Radioactivity Measurement Station—a privately run radiation detection lab in a downtown mall—to have her dosage measured.

The Wakamiya evacuee housing complex in Koriyama city is giant grid of prefab buildings—570 units in all—erected on a field of gravel and asphalt. In the middle is the Odagaisama Center: a community building with a recreation room and a radio station that broadcasts news and music to evacuees.

In the Fukushima exclusion zone, many abandoned houses look as if the residents walked out just yesterday—except for the dead plants and the 2011 calendars on the walls. In this home in Shiroishimori village, the electricity is surprisingly still on. An aquarium keeps pumping water, even though the fish have long since died.

Hisako Oe, director of the Fukushima Organic Farmers Network, shows off her enormous garden of tomatoes. “Organic farmers are so proud of what we are doing,” she says, “and then we get condemned as murderers for growing here. It’s so painful.”

A nestful of newly hatched chicks born on a wooded hilltop above Chernobyl’s cooling pond, being held by ornithologist Igor Chizhevskiy, who works for Ecocenter, a government research lab, in the exclusion zone. His research compares birth and survival rates of birds born in highly radioactive sites with those in less contaminated areas within the zone. The diminished populations in hotter areas could be directly caused by radiation or may be a secondary effect, due to a decrease in food sources such as insects.

The central square of Pripyat is overgrown with trees. The city of almost 50,000 was evacuated in a day, while firemen tried fruitlessly to douse the fire in the reactor. Tourists visit on weekly guided excursions, their shouts ringing across the plaza. When former residents visit, they search quietly, struggling to match old memories with the scene before them. Others refuse to return, preferring to recall their hometown as they knew it: a paradise lost.

Every evening after dinner, plumber Masayuki Nagai in Koriyama pores over the radiation reports. The average daily dose for each city is monitored by government equipment and printed in newspapers alongside the weather.

Anti-nuclear protestors chant, “No more Hiroshima, no more Fukushima” and other slogans as they march through the streets of Tokyo to a rally outside of Japan’s parliament. Police did not let protestors into the square in front of the building until the crowds surged through the barricades. Demonstrators filled the square for about 40 minutes before the rally ended peacefully. In Japan, where public protest is rare, weekly nuclear protests have become the largest demonstrations since the 1960s.

In Sukachi, 18-year-old cousins Yulya and Alina, and a friend, graduate this week from high school. Tonight, the class celebrates at their prom, with a grand banquet and dancing. After graduation, will they stay?

From Michael Forster Rothbart‘s 2013 TED book, Would You Stay? Part of Forster Rothbart’s After Chernobyl project ran in 2010 on MotherJones.com: “Chernobyl’s Half Lives.“