McKenzie Funk

In his new book, Windfall, journalist McKenzie Funk visits five continents to bring back stories of the movers and shakers at the forefront of the emerging business of global warming. He introduces us to land and water speculators, Greenland secessionists hoping to bankroll their cause with newly thawed mineral wealth, Israeli snow makers, Dutch seawall developers, wannabe geoengineers, private firefighters, mosquito scientists, and others who stand to benefit (at least in the short term) from climate change. (See this short excerpt, in which he writes about a guy who launched the world’s first water rights hedge fund.)

Windfall is fascinating, entertaining, and ultimately troubling as the author uncovers more and more evidence of what he calls the implicit “unevenness” of global warming, and the futility and/or unfairness of our approaches to dealing with it. I reached Funk at his home in Seattle to chat about California’s impending drought, why man-made volcanoes won’t save us, and how Hurricane Sandy (figuratively) blew him away.

Mother Jones: How do you suppose your water hedge fund guy, John Dickerson, feels about California facing its worst drought in 40 years?

McKenzie Funk: He doesn’t consider himself a bad guy. He thinks that he plays a necessary role in moving water from where it is to where it needs to be for things to happen, and I respect that. He told me that California is a bit of a harder market to enter, mostly because there are a few others doing this, and a lot of his plays have been farther upstream in the Colorado system, so I don’t think it’ll have a huge effect on his bottom line immediately.

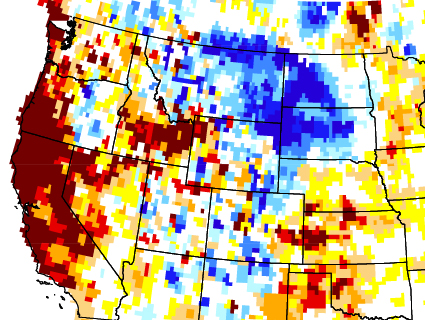

MJ: But drought in California will affect water futures in other states, right?

MF: It could. One thing that was happening before was that California was getting the extra water from the other states. There was enough surplus that California was able to keep going on what the others weren’t using. That’s stopped. The shit is hitting the fan with the Colorado River Compact. It’s a good time if you’re a water investor. It’s now tight; it’s the market we’ve been expecting. Before this, a lot of what was driving water markets was the housing boom—developers needed water for new houses. That was an artificial driver. This one is natural.

MJ: How will having Wall Street guys buying up water rights affect everyday folks in the Southwest?

MF: Their argument is that everyday people in the Southwest are those who are moving to the city. Right now a bunch of ranchers whose sons don’t want to ranch anymore, whose kids have gone away, are sitting on all this water. The argument is that by buying up this water and packaging it and selling it to the cities downstream that need it, [the hedge funds] are helping the West grow. The Sun Belt is where we’ve had all this population growth, and it’s been sort of artificial—we’ve had to move the water there. This helps that happen on a systemic level, setting us up for a bigger fall.

MJ: Will people have to pay higher prices?

MF: Any time utilities try to raise the rates too much, regulators cry foul. But at a certain point, if these utilities aren’t allowed to let the market do its thing, it’s just going to be too expensive for them. That’s when these guys who are holding the water, who are creating artificial aquifers to sell to the utilities, are going to make a ton of money.

MJ: Should water be more expensive?

MF: There is a viable argument for water being more expensive in areas that don’t naturally have a lot of water. It encourages conservation. That’s obviously a very market-based argument, and markets don’t always work. But water is so cheap you don’t think about it. In Seattle, we’ve got tons of water in theory, and yet our prices are some of the highest in the country. It’s absurd. But at my house, we’re very careful about showers and watering our lawn and whatnot, because it costs so much.

MJ: The business world clearly knows that climate change is real and is betting a fortune on it. So why do you think a record 23 percent of Americans, according to recent polling, now say climate change isn’t happening?

MF: I don’t know, except to say that that 23 percent does not overlap with the captains of industry. ExxonMobil now admits that climate change is real and is talking about pricing carbon; it’s got an internal carbon price and it’s thinking about cap-and-trade and has spoken in favor of a carbon tax. If you’re interested in making money, you have to be interested a little bit more in reality than if you’re waging a political battle.

MJ: I was fascinated by your chapter on Shell Oil’s climate risk scenario planners. Tell our readers a bit about that program.

MF: It’s sort of a futurism that they helped develop back in the ’60s and ’70s. Every five or so years they come out with new scenarios—stories about what the future could be. Sometimes there are competing stories, two or three versions of what the world could look like, and they flesh them out internally and externally so they can have their analysts really think about what they would do if that particular reality came to pass. In 2008, Shell released two scenarios: Blueprint and Scramble. Blueprint was an approximation of the world as we want it to be, which is to say there’s [climate] action at a local level but also at an international level eventually to cut carbon emissions and move to greener sources of energy. That was their happier scenario, and they also said for the first time that was the scenario they preferred.

MJ: What about the rival scenario?

MF: In Scramble, events outpace actions on climate change: It’s a race for coal, a race for resources, and our energy systems don’t keep up with demand at all, and certainly they don’t go greener than they are. So, heavy reliance on fossil fuels—particularly coal. At the end of 2012, I think, I asked them, “Have we gone to Blueprint or have we gone to Scramble?” The head of their scenarios team said. “We’ve gone to Scramble. This is a Scramble kind of world. This is what we’re doing.”

MJ: We talked about the water hedge fund guy. Who are some of the other winners in the climate game?

MF: Well, potential winners, short term. Long term, everybody loses. Short term, the winners would be those who are buying up farmland in Africa or eastern Europe because they expect food prices will go up. The people of Greenland who want to have independence and need to be able to pay their own way rather than get subsidies from Denmark. They think they can drill their way to independence with their huge oil deposits and lots of onshore minerals as they get uncovered by climate change. The shipping season is getting longer; shipping over the Arctic is an obvious example. The desalination businesses—all these places that are water-stressed even before climate change: Israel, Spain, Australia, Singapore are now the leaders in the desalination industry and they’re exporting this technology.

MJ: Given your chapters on land grabs in Africa and climate refugees in Bangladesh, what kind of climate-related geopolitical upheaval might we expect this century?

MF: People who deal with refugee issues don’t like the term “climate refugees,” but that seems to be one of the major concerns. Some countries are going to run out of places to go. Bangladesh is a good example, island nations are others. There will be parts of most continents where people will be displaced: New Orleans, where people suddenly end up in trailers in Texas. I had conversations with intelligence officials, and they’re really worried about things like refugees coming to our borders or refugee issues in Africa and then the US gets pulled in as the world’s policeman. They’re worried about that much more than they are about, say, a fight over resources in the Arctic with a bunch of other stable powers.

MJ: They don’t think that’ll happen?

MF: Well, they think there’s going to be a legal squabble. I thought of it as: You go to a birthday party for a kid and everybody gets a big piece of cake, and one guy gets a slightly bigger one. That’s what’s happening. You’ve got five nations—us, Canada, Denmark via Greenland, Norway, and Russia—all getting a very massive chunk of the Arctic, with a ton of oil deposits, but I don’t think there’s much fighting over it. But where resources are becoming scarce and we’re talking about running out of water or food—and, you know, land is pretty cool to live on!—that’s where the intelligence community is worried.

MJ: You hung out with geoengineers who think they can cool the planet by spewing sulfur particles into the atmosphere. But there’s a big tradeoff, right?

MF: Yeah. They talk about how it’s relatively easy and it’s been proven by volcanoes that you can stabilize the temperature, and I think that’s true. Scientists don’t seem to disagree that geoengineering could take the temperature down. But bringing back our old climate is quite different. Taking the temperature down would not fix the rainfall patterns, and particularly not with the places where some of the geoengineers are talking about releasing sulfur: over the Arctic. There are early suggestions—it’s not finished science—that the monsoons would get messed up over India, and there’d be massive famine and massive water problems, either drought or too much water in places already on the edge.

MJ: So what helps some of us could be bad for others.

MF: Yeah, and that’s the worry with all these technologies. Either the rich are going to be able to get richer from the ice melting in the north. Or the rich are going to be able to wall off their own patch of the Earth, and they’re certainly not going to get hit as hard as the others do. Whether we’re talking about outright winners or relative winners, it’s clear that the biggest losers are the poorest of the world. That was something that was really stark the more I went around, seeing who can pay for these things that might save us. Well, people like me can.

MJ: What surprised you most?

MF: I was reporting it before Copenhagen, when we were supposed to have these big climate accords. Obama was elected, Copenhagen was coming up, and suddenly you had this climate bill in the Senate. I thought, as I think a lot of people did, that there’d be tangible action on climate change. I didn’t think that the bet on failure would be such a good bet, and I don’t have much joy in having chosen the right thing here. I was sort of shocked that politics hadn’t moved a bit on cutting emissions.

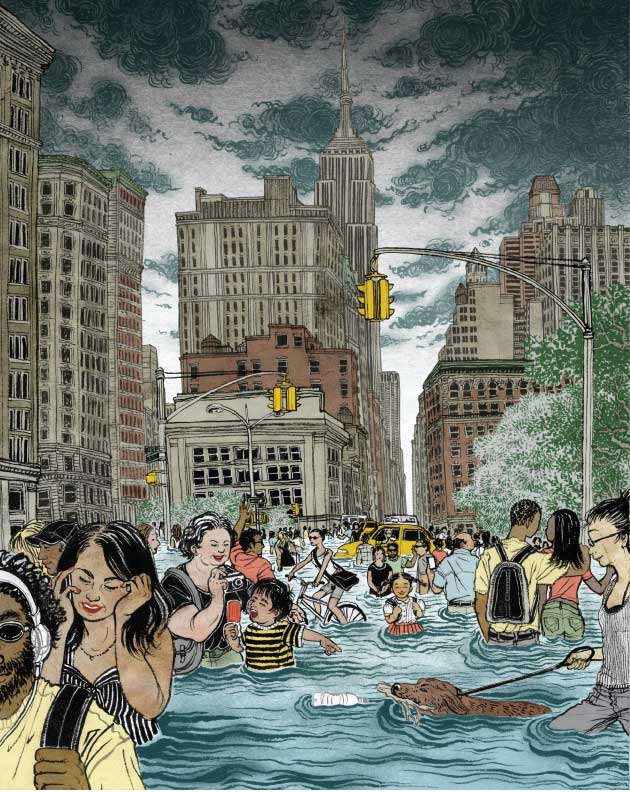

The second surprise was Hurricane Sandy. Not that it happened, but because it was so perfectly predicted what would happen—if a hurricane of this size hit, and a storm surge hit when the tide was high—to the subways, which subways, which neighborhoods in New York City. All of this was predicted by these scientists whom I had met or heard speak. I’d read their papers. When Sandy hit, on a personal level I was like, “Holy shit, it’s just what that guy said!”

MJ: What’s the message you hope your readers take away from Windfall?

MF: The fact that mitigation is relatively democratic—cutting private emissions helps everybody—but adaptation, which is more and more what we seem to be going toward, is not at all democratic. In fact, it is deeply unfair. I think everybody needs to understand that. We talk about climate change as this tragedy of the commons, which kind of takes some of the moral oomph out of it—like, we’re all doing this, we’re all screwing ourselves. But that’s not a very good frame for what climate change really is. It’s not even at all. It’s not even geographically. It’s not even economically. So for those of us who have the highest historic emissions—in North America and Europe and, increasingly, China—to be able to buy our way out of this problem or to profit off it is systemically dangerous. It really raises the moral stakes. I don’t want to villainize the individuals I met, because by and large they’re good people doing things they believe in. But I think we all need to step back and understand what the stakes are.

The second thing isn’t a moral point, but sort of a practical point: We can’t trust capitalism to just fix this. We can’t trust self-interest to fix this. If those who have the most to gain from climate change happen to be the ones who are emitting the most carbon—if I’m that person, am I really going to do too much about climate change, just to save myself?

Click here to read a short excerpt from Windfall.