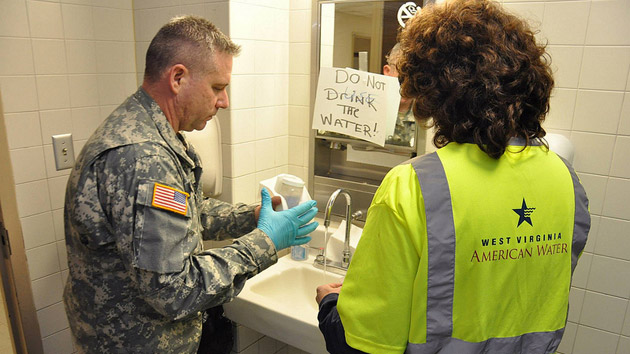

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/thenationalguard/11928193404/">The National Guard</a>/Flickr

This story originally appeared on the Huffington Post and is republished here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The 300,000 residents of nine West Virginia counties affected by last Thursday’s chemical spill are slowly starting to get notice that they can turn on their taps again. But many are still wondering why they didn’t have more information about the potential dangers in their own backyard.

As much as 7,500 gallons of 4-methylcyclohexane methanol (also known as crude MCHM) spilled into the Elk River about a mile and a half upstream from where the West Virginia American Water utility draws its supply. The coal-cleaning chemical came from a storage facility owned by Freedom Industries and located in Charleston, the state capital.

Angie Rosser, executive director of the West Virginia Rivers Coalition, lives along the Elk River upstream from the spill. Even though she works on environmental issues and drives by the storage facility regularly, she said she had no idea that the tanks held chemicals. “They just look old and rusty,” Rosser told The Huffington Post. “I just couldn’t have imagined. If I knew, our organization certainly would have raised questions about this.”

“But we are in the same boat as the rest of the public, the water company, and apparently our governor,” Rosser said. “No one seemed to be aware or care that this dangerous chemical was upstream from our largest drinking water intake in the state. It was a recipe for disaster.”

That seems to be the resounding complaint in West Virginia: No one knew. The chemicals were disclosed in a filing to the state last year, reporting that the facility could hold anywhere between 11.4 million and 63.5 million pounds of 10 different chemicals on a given day, including up to 1 million pounds of MCHM. The forms were filed in compliance with the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, a 1986 federal law designed to make sure plans are in place in case of an accident. MCHM was listed on the Tier II reporting form as a “hazardous” material under the Environmental Protection Agency’s classification system. But there doesn’t seem to have been a plan in place in case of an accident, as the Charleston Gazette has reported, and the public didn’t know the chemicals were there.

West Virginia lies in the heart of coal country, which means MCHM is likely kept in not insignificant quantities at storage and preparation facilities across the state. Moreover, after the chemical is used to wash the coal, the tainted wastewater is often injected into old mines or stored in above-ground impoundments.

Yet finding out where else such chemicals are stored in the state is difficult, environmental advocates say. The forms disclosing the chemicals are filed with the West Virginia Department of Military Affairs and Public Safety. Communications director Lawrence Messina said the department keeps the past five years of filings, but most of them are on paper–because most of the roughly 9,500 facilities in the state that file these reports still turn them in that way. Electronic filing has only recently become an option, and the department itself does not offer a publicly available online database. Individuals can request a filing for a particular facility, presuming they know of its existence, and county emergency planners keep copies of the filings for their local sites. So some information exists, but there’s no easy way to search it by location or chemical.

Coal field activists warn that while the spill in Charleston is a big deal, many in the state could potentially be exposed to the chemical on a daily basis. “It’s a big emergency here based on the fact that 300,000 people’s water source was polluted, but the story here is that coal companies use this chemical and other chemicals in West Virginia every day,” said Bill Price, a West Virginia-based organizer with the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign.

West Virginia Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin (D) tried to put some distance between the coal industry and the spill. “This was not a coal company incident,” Tomblin said. “This was a chemical company incident.”

But Price said that’s not much of a distinction. “Let’s be honest, the reason it was stored in Charleston is its proximity to coal-producing areas,” said Price. And he added, “We don’t know where else this chemical may be stored.”

Safety concerns related to MCHM and other chemicals used by the coal industry have been raised before. Residents in several parts of the state have filed lawsuits regarding the underground disposal of coal slurry, which can contain MCHM and a number of other chemicals. Plaintiffs from Mingo County reached a settlement with Massey Energy in July 2011 after alleging that 1.4 billion gallons of coal slurry had contaminated their groundwater. More than 350 residents of Boone County reached a settlement over coal slurry contamination claims in June 2012.

Jack Spadaro, a former superintendent of the National Mine Health and Safety Academy (a program of the US Department of Labor), testified as an expert witness for the plaintiffs in both those cases. He said that the use of MCHM is fairly common in the state. “It’s used in virtually every coal preparation plant in the coal fields, this chemical or something like it,” he said.

Concerns about potentially tainted groundwater prompted the state to put a moratorium on new underground slurry injection sites in 2009, though underground injection is still allowed at sites that already had permits.

And the problem is not confined to MCHM. Finding out how many major chemical facilities there are and the quantities of any chemicals they store is hard, said Maya Nye, spokesperson for the citizen group People Concerned About Chemical Safety.

Nye has advocated for tougher chemical oversight and transparency rules in the state for years, following two previous incidents: an August 2008 explosion at a Bayer CropScience plant that killed two workers and a January 2010 toxic release at a DuPont facility that killed one person. But the state failed to put in place tougher rules, even after the US Chemical Safety Board recommended them, the Gazette reported.

To find out how many chemical facilities with “extremely hazardous” substances–that is, those deemed more dangerous than the merely “hazardous” MCHM–were located in her area, Nye had to go to the EPA’s reading room in Washington, D.C., and take handwritten notes on all the risk management plans filed for the region. Photocopying and photographs were not allowed.

Many of the area facilities that reported extremely hazardous chemicals “were not on my radar,” said Nye. Even for the ones that were, she was surprised by the volumes stored on site. “I was not aware of the amount of danger we were in,” she said.

The two previous chemical incidents did not, however, lead to changes in state laws regarding chemical safety and public reporting. “I don’t think there’s any major political interest in trying to more heavily regulate the coal or the chemical industry in our state, because they are huge economic engines,” said Nye.

Maybe the latest MCHM spill will prompt reforms.

“The fact that 300,000 people are exposed means that someone is probably going to be willing to champion it now,” said Nye. “I don’t want to have to wait for disaster to occur to get on top of things, but that seems like that’s the only way we deal with things in this state or this country.”