FDA.gov

On Thursday, the Food and Drug Administration and first lady Michelle Obama unveiled proposed changes to the classic black-and-white nutrition label, which had gone 20 years without a major update. The proposed requirements make labels less confusing to consumers, while drawing attention to serving size and calories—a move that public experts say could help curb obesity.

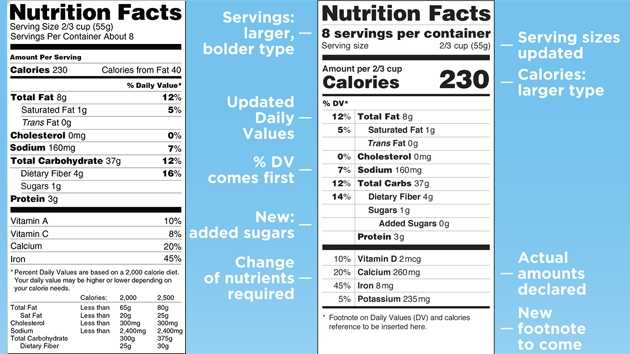

What’s different about the new labels? The most eye-catching aspects of the FDA’s proposed revamp are larger, bold calorie count and “servings per container” labels.

Also, for the first time, nutrition labels will break out the amount of sugar added during the production process. Studies have linked added sugar to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, heart attacks, and strokes. The label change could help consumers reduce their intake of added sugars, which has been recommended by the Daily Guidelines for Americans, the Institute of Medicines, the American Heart Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the World Health Organization.

The proposed label includes several other tweaks:

- The inclusion of vitamin D, which promotes bone health, and potassium, which helps lower blood pressure, will be required. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey suggests these nutrients are likely to be underconsumed in the US population. These items, which will join calcium and iron toward the bottom of the label, will have actual quantities listed in addition to daily value percentages. Listings for vitamins A and C, currently required, will become voluntary.

- “Calories from Fat” will be removed to avoid distracting from the more meaningful total fat, saturated fat, and trans fat listings.

- Revisions will be made to the recommended daily values of sodium (2,400 mg to 2,300 mg), dietary fiber, vitamin D, and calcium (1,000 mg to 1,300 mg). Under these changes, for example, a cup of milk containing 300 mg of calcium would have a % daily value of 23 percent instead of the current 30 percent.

Although changes may still be made to the proposed labels, Michelle Obama stated:

No matter what the final version looks like, the new label will allow you to immediately spot the calorie count because it will be in large font, and not buried in the fine print. You’ll also learn more about where the sugar in the food comes from—like whether the sugar in your yogurt was added during processing or whether it comes from ingredients like fruits.

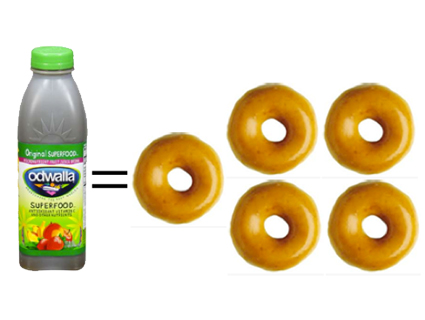

What other changes are involved? In addition to altering the layout of items within the nutrition labels, the FDA proposes changing the way serving sizes are calculated. Current serving sizes are based on the amount people should eat, not how much they actually consume. A quick glance at the nutrition label on a 5.3-ounce bag of M&M’s shows 220 calories—but snack on the entire 3.5-serving package and you’ve actually consumed 770. A 28-ounce (2.5 serving) bottle of Gatorade lists 80 calories, but contains 200.

Under the proposed new requirements, packages that tend to be treated as single servings will be listed as such—increasing the guilt level of consuming an entire package in one sitting.

Larger packages that could potentially be eaten in either single or multiple servings will have “dual column” labels listing both “per serving” and “per package” calorie and nutrition information.

Do the changes go far enough? Overall, nutrition experts seem pleased with the proposed emphasis on calories, serving sizes, and sugar. Marion Nestle, a nutrition expect and New York University professor, praised the proposal in her Food Politics blog: “Congratulations to the FDA for a job well done and to Let’s Move! for inspiring changes and moving them along.”

But there are lingering concerns with current labels that have not been solved in the new proposal. For example, the proposed label does not address the fact that the FDA currently permits five different methods of measuring total calories and allows for a calorie-count margin of error of 20 percent.

The Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) urged the FDA to take the “Added Sugars” addition a step further by including a “% Daily Value.” It recommends basing this on a maximum daily intake of 25 grams (about six teaspoons), just one quarter of the average American’s current added sugar consumption. CSPI also recommends further decreasing the daily value for sodium to 1,500 mg.

What prompted the changes? Labeling changes have been in the works for 10 years, and more recently, Michelle Obama and her Let’s Move! staff helped push along the revisions. The primary goal of the proposal is to “better help consumers make informed food choices and follow healthy dietary practices.”

“Obesity, heart disease, and other chronic diseases are leading public health problems,” stated Michael Landa, director of FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. “The proposed new label is intended to bring attention to calories and serving sizes, which are important in addressing these problems.”

The FDA estimates that the changes may generate $20 to $30 billion in health benefits to consumers over 20 years.

How long before the new labels appear on shelves? The FDA’s current proposal will be open for public comment for 90 days. The finalized regulations are expected within one year, and companies will be given another two years to update packaging.

How has the food industry responded? The FDA estimates it will cost the food industry about $2 billion to update the nutrition labels that appear on approximately 700,000 consumer products.

Despite the hit the proposed labeling may take on food and beverage sales, the Grocery Manufacturers Association has been supportive of the revisions. “It is critical that any changes are based on the most current and reliable science,” CEO Pamela Bailey said in a statement. “Equally as important is ensuring that any changes ultimately serve to inform, and not confuse, consumers.”

The Sugar Association, which has worked for decades to fight scientific claims on the danger of sugar, was quicker to criticize. “Added sugars’ labeling will only distract from the focus on monitoring total caloric intake and scientifically verified interventions to deal with obesity,” CEO Andrew Briscoe told the Huffington Post. “Consequently, the addition of the ‘added sugars’ subcategory will not be helpful to consumers, and lacks scientific merit.”