Ian Tyson and Jessie VeederNational Cowboy Poetry Gathering

One snowy week near the end of January, the halls of the Elko Convention Center are abuzz with the tipping of hats and toasting of beers. Thousands of cowboys and girls had descended on the small northern Nevada city from all over the West for the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, the oldest—and one of the largest—of the various gatherings celebrating America’s waning ranching lifestyle.

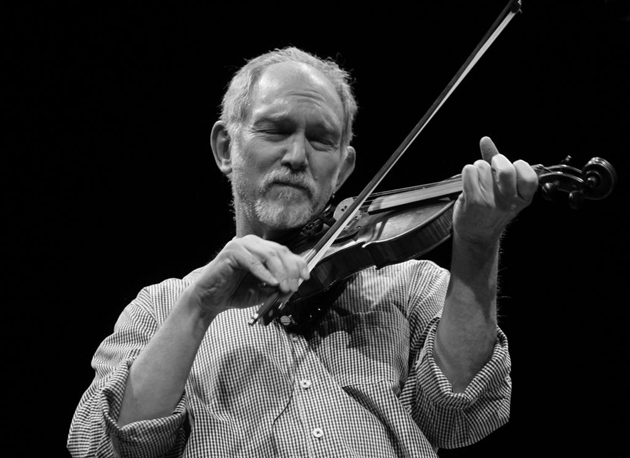

Performing on the main stage on a Thursday night, Jessie Veeder doesn’t exactly match the current cowpoke demographic. She has dark curly hair, and wears a brightly colored top and pleather pants. More notably, though, she’s only 30—the same age as the gathering itself—which makes her a good deal younger than the average participant. The next night, 80-year-old Ian Tyson, a classic cowboy musician, would headline this stage in classic ranch-hand gear, crooning: “Everything’s fast forward now, years are flying by. Man, that can really fuck up a 1950s guy.”

Veeder’s showcase, “Straddling the Line,” features a bill of younger talents who are taking the torch from Tyson’s generation and adapting it to their own. It’s part of an ongoing effort by the festival’s organizers, who are desperate to diversify and expand the cowboy niche. The Elko shindig also includes panel and group discussions on the decline of ranching and the challenges facing the rural West. After all, what is cowboy poetry and music without cowboys?

There was once a time, at the turn of the 20th century, when half of America grew food. But the number of cattle raised in the United States is at its lowest since 1952. And nearly two-thirds of Great Plains counties declined in human population between 1950 and 2007—69 of them by more than half. There are plenty of reasons for these numbers: the industrialization of agriculture, encroaching development, battles over the use of public land for grazing, and an aging population. Ranching is increasingly unprofitable—feed prices have doubled in recent years—and the children of ranching families are fleeing for financially greener pastures.

By 2007, the number of farm and ranch operators younger than 35 had dwindled to 5 percent, down from 16 percent in the early 1980s. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that by 2020, agricultural operations will have shed 96,000 jobs (8 percent of the total), the largest decline of any occupational category.

Veeder is defying the trend. Three years ago, after college and a period of employment and touring, she moved back to the 100-year-old North Dakota ranch where she grew up. The day after her show, she participates in a panel called “Back on the Ranch” with three other young ranchers who followed a similar path.

As a musician, Veeder tells the audience, she is frequently asked why she lives so far from cultural centers like Nashville or Austin. She describes how she grew up riding horseback through the beautiful buttes alongside her father. To afford that kind of lifestyle, her dad had to work a professional job during the day. “I understood the sacrifice it took to keep a place like that intact and in the family, to continue the legacy,” she says. “I saw the work and the struggle, but I saw the passion.” The other panelists agree. “It’s not a great living, but it’s a really good lifestyle,” one adds.

Her connection to the land, and the hardships that go with that, is something Veeder explores in her lyrics. The words have always been front and center in cowboy music. Many of the songs have their roots in cowboy poetry, which harkens back to after the Civil War; bored cowboys picked up on a British Isles tradition, and started writing poems influenced by Spanish lingo and the songs of soldiers. The first collections of cowboy songs, in the early 20th century, paid little attention to melody. It was often just poems set to a tune. “Them that could sing usually did,” the poet and musician Dale Girdner once told Charlie Seemann, who runs the Western Folklife Center. “And them that couldn’t carry no kinda tune would usually just say the verses.”

The song “Boomtown,” Veeder explains during her performance, is an ode to her hometown of Watford City, which has ballooned from 1,200 to an estimated 10,000 people in the past six years due to the Bakken oil boom.

Stopped by the farmhouse the other day

Jimmy’s moved back home he’s helping dad cut hay

Pumps in the morning but he gets home by 5

We almost lost him there

Now he’s more alive

God bless the sound

Boomtown

Jimmy’s story is not too distant from her father’s—or her own. To make ends meet, Veeder’s husband works for Marathon Oil, and she works as a communication specialist, freelance writer, and musician. Ranching is their labor of love.

The festival’s attendees are also grappling with a changing rural landscape. Novelist Johanna Harness traveled all the way from Nampa, Idaho, to Elko to give her kids a taste of the culture. I meet her at an open discussion called “Into the Future,” held in a convention center room divided up by theme.

She and her kids had joined the Youth and Economics group. A large sheet of paper on the wall nearby bears questions scribbled in marker: “If there were no limitations, what is your vision of the West/rural you want to build? What is the story about the future you want to tell?”

Ivy, Harness’ 8-year-old, is curled up on the floor, a purple bandana around her neck, absorbed in drawing the family’s large converted red barn. Virginia, 15, takes notes while her brother Paul, 12 looks on bright-eyed, clad in a cowboy hat and sneakers. It’s the family’s second year at the fest, and Harness says she gets choked up just thinking about it. The poems and songs “are memories that my grandparents told me—and they’re gone now.”

She’s part of the first generation to leave the farm and attend college, but she misses the tradition of agricultural work. Her mother moved from Kansas to Idaho during the Dust Bowl at the chance of employment, only to give up the farm they lived on soon after for health reasons. Her father, the youngest of 11 children, dropped out of school at age 15 to work full-time, but the family still couldn’t make things work financially.

“There has to be a way for people to make a good living so that people can commit to that lifestyle,” another member of the Youth and Economics group comments in a hushed rant. “A lot of ranchers need to be more businesslike, and I would whisper that, because we’re just doing that now in our 84th year. You can’t fall in love with your cows; you can’t fall in love with the old photos. You’ve got to put numbers on things and you’ve got plan ahead.”

Harness understands all of this. But “these are my roots,” she tells me. “This is incredibly important to me…I want my kids to hear these stories and know who they are.”

Virginia, Harness’ eldest, considers herself a “rural person”—one who always wants the elevation of the town she lives in to exceed its population. But she doesn’t think she wants to go into ranching. “How sustainable would it be for me to do that?” She would probably have to work a second job in town. Instead, she hopes to work in politics, lobbying for rural causes. Attending the festival has been “a form of education,” she says. “Rural people aren’t stupid. That stereotype is really harmful to teens and kids in rural communities.”

Roaming the center’s halls, an 11-year-old named Colton Lee is dressed in knee-high Tony Lama boots, Wranglers, a pocket watch, wool vest, polka-dotted wild rag, and Justin cowboy hat. He learned the ins and outs of cowboy attire on his dad’s ranch in Hudson, Colorado, although he doesn’t get to wear it all the time (during PE, for example).

But Colton, who aspires to be a rancher and a veterinary surgeon, brings a cowboy perspective wherever he goes. Like his father, and unlike most of his peers, he isn’t into the internet. He’d rather listen to cowboy poets like Paul Zarzyski. And the ranching lifestyle still appeals to him, even if it’s a struggle.

“It’s worth it,” he says, wracking his brain for the title of a song he knows that says it perfectly. He can’t quite recall it, but he remembers the sentiment well enough: “You’re rich, but you’re broke.”