Sue Ogrocki/AP

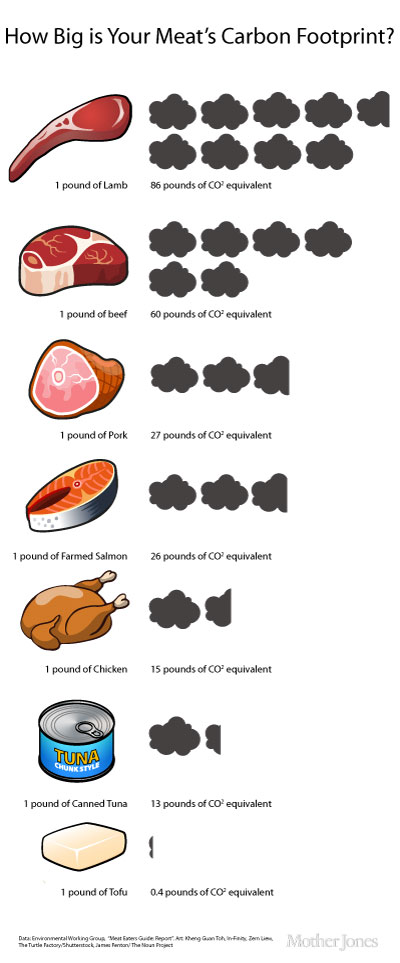

As Josh Harkinson noted this week, cows are the United States’ single biggest source of methane—a potent gas that has 105 times the heat-trapping ability of carbon dioxide. That’s one major reason why beef’s greenhouse gas footprint is far higher than that of most other sources of protein, according to an EWG study. (Though it’s consumed at a fraction of the rate of beef or chicken, lamb is by far the most carbon intensive of the major meats, according to EWG, since the animal’s smaller body produces meat less efficiently but still produces a lot of methane.)

And EWG’s estimate of beef’s impact may actually be on the conservative side: A study released this week found the greenhouse gases associated with beef to be even higher.

So what should you eat instead of beef? One answer: chicken, which has a carbon footprint roughly a fifth the size of beef’s. Happily, earlier this week, the National Chicken Council released new research showing that Americans are eating chicken in 17 percent more meals and snacks than they did in 2012. As the chart below shows, chicken consumption has actually been rising steadily for decades. Red meat consumption, meanwhile, has steadily declined over the same period.

The group attributes the spike in chicken consumption to consumers’ perception of poultry as healthier than beef, not its smaller carbon footprint. But the environmental benefits are a great side effect, says Emily Cassidy, an analyst at the Environmental Working Group. “If every American simply switched from beef to chicken, it could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 137 million metric tons of carbon a year, or as much as taking 26 million cars off the road,” she says, citing a recent EWG report.

Still, even as the American appetite for beef has declined over the years, other countries are picking up the slack. Globally, beef and veal production has increased almost 20 percent between 1995 and 2012, according to the Organization for Economically Developed Countries. It’s projected to increase another 11 percent by 2022, a trend that’s largely driven by rising incomes in Asia (and, increasingly, in Africa).

In the face of this environmental onslaught, says Cassidy, really measurable change could only happen if everyone ate vastly less meat—and the only way to achieve that is to change policies that favor livestock feeds like corn.

“Essentially, cheap corn encourages meat to be a big part of our diets,” she says. “If crop subsidies were reined in, meat and especially beef consumption would likely go down.”