Gertrude Bell, a pioneering archaeologist who excavated sites in the Middle East<a href="http://www.gerty.ncl.ac.uk/">The Gertrude Bell Archive, Newcastle University</a>

One of the most difficult parts of getting a Ph.D. is finishing your dissertation. Those last three months were certainly the hardest of my life. Beyond the mountain of work a dissertation requires, graduate students also have to face feelings of inadequacy, disappointment, and anxiety about the looming job search. Sometimes, they need a gentle, supportive push to quit stressing about every last comma and—after years of blood, sweat, and tears—finally turn it in.

So when Kate Clancy, an anthropologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, chided an old friend who was still a graduate student about taking that last step to finish her thesis, she thought she was doing her a favor. But she was floored by her friend’s response.

Clancy remembers her friend saying, “Well, I was sexually assaulted in the field, and every time I open the dissertation files I have flashbacks.” On this week’s episode of the Inquiring Minds podcast, Clancy goes on to say that conversation “was the first time that it really hit me how much these kinds of experiences can not only emotionally traumatize women, but also explicitly hold them back in their research.”

So she joined up with three fellow female scientists to study the extent to which sexual harassment and sexual assault occur in the field. On this week’s podcast, the four coauthors—Clancy, anthropologists Robin Nelson and Julienne Rutherford, and evolutionary biologist Katie Hinde—discuss their recently published survey of scientists who have worked in the field.

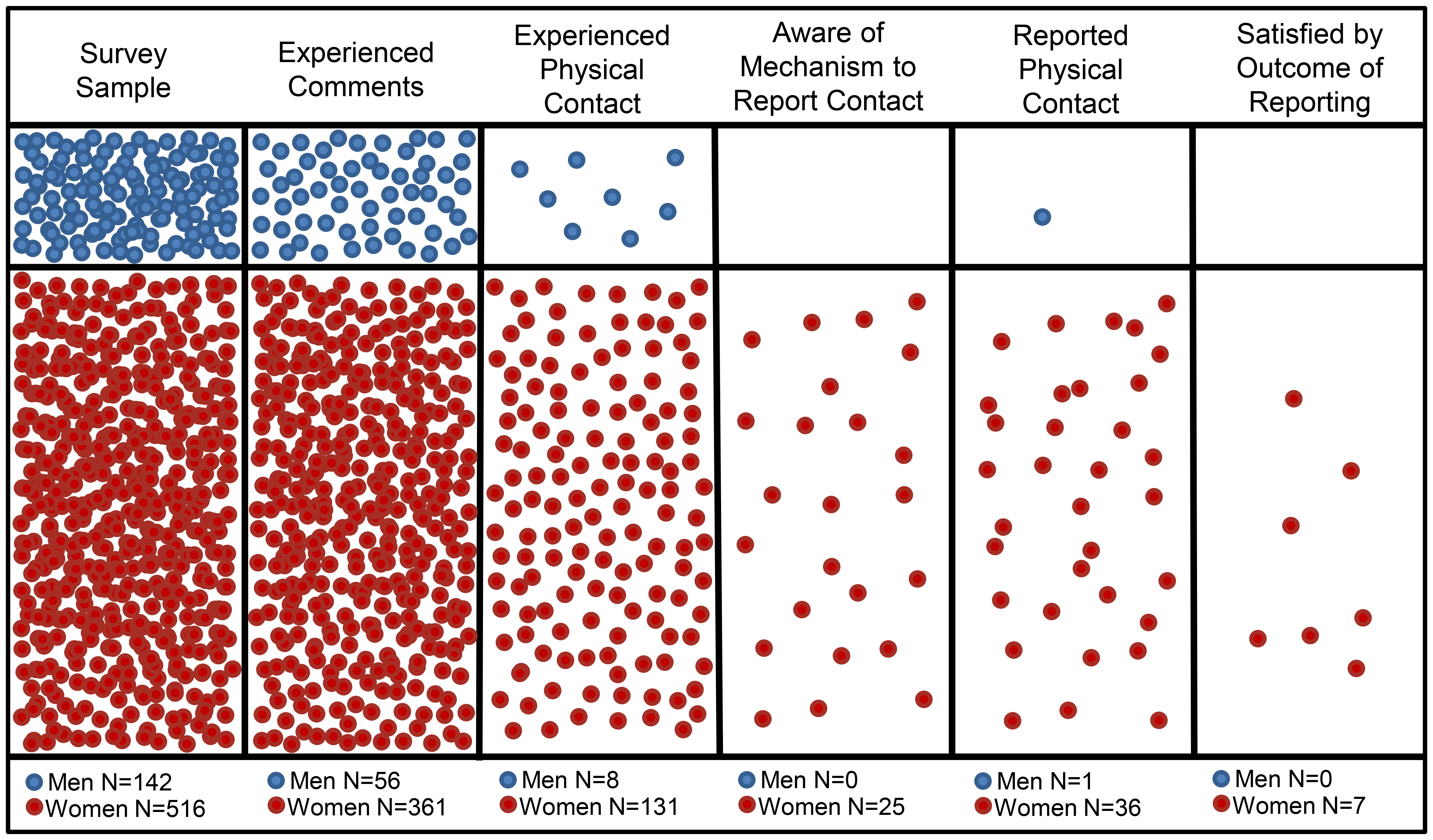

Their results were eye-opening and immediately generated headlines. “Around 70 percent of women from our sample reported experiencing harassment and about 40 percent of men,” Clancy says. Additionally, 26 percent of women and 6 percent of men reported being sexually assaulted (defined as “unwanted physical contact”) while doing field research. Nearly all of the women who reported assault or harassment were students, post-docs, or employees—rather than faculty members.

Field work is a highly-sought-after experience during scientific training in biology, anthropology, and other disciplines. As the study authors note, many universities require at least one field work module to earn a degree, and scientists who engage in field research publish more and secure more grants than those who do not. What’s more, despite the fact that more women enter and complete Ph.D. programs in biology and anthropology, women are less likely than men to maintain fieldwork throughout their careers.

There’s been a lot of debate concerning why, with an increasing number of Ph.D.s going to women, women remain underrepresented in the top tiers of science. This is a complicated and thorny issue, but Clancy and colleagues have added yet another data point: Women might be leaving some disciplines in order to avoid unwanted sexual comments and contact, especially in the field.

So how did the researchers arrive at these results?

Relying on social media and other outlets to recruit survey-takers, Clancy and her colleagues managed to collect 666 responses, 77.5 percent of them from women.

As the authors note, their sample might overrepresent people who have had negative experiences, as these individuals might be more likely to respond to the survey request. But it might also be an underestimate: “We received information from some folks who said, ‘I would love to do your survey, but I can’t do your survey because it would trigger me in having to think about this traumatic experience that I had in the field,'” says Nelson, who is an assistant professor at Skidmore College.

Importantly, the study’s findings go beyond simply documenting that women are far more likely than men to be sexually harassed or assaulted in the field. Women were also more likely to report that they were harassed or assaulted by superiors. Men, by contrast, were more likely to be harassed by their peers. “There is a whole literature on sort of the directionality of sexual harassment, and there’s much greater psychological harm when it’s a vertical abuse, meaning coming from someone higher up in the hierarchy,” Clancy explains. “And so not only are women experiencing harassment and assault in greater numbers than men, but the actual nature of the assault potentially can cause greater psychological harm.”

What’s so special about field work that might explain these findings? “Our data can’t speak to specific environments within the lab or the office,” says Rutherford, an assistant professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago. “But there are some aspects of field work that I think contribute to these kinds of behaviors, and that is there is often a certain amount of confusion about who is in charge…some field sites are run by investigators from multiple universities, and research institutions; there might be a field school where you’ll have students from many different universities—so the overseeing institution may not be clear to any individual participant in any stage in their training or in the hierarchy. So that confusion contributes to, I think, a loosening of boundaries.” And then, of course, there are the practical considerations: Scientists are far away from home, their families, other responsibilities, and social networks that both serve to keep bad behaviors in check and provide support to victims of abuse.

Indeed, the study found that only about 1 in 5 respondents who had been harassed or assaulted were “aware of a mechanism to easily report” the incidents at the time. And of those who did file reports, less than 20 percent said they were satisfied with the outcome.

So what are the next steps? “We put this paper out there as a start of a conversation,” says Hinde, an assistant professor at Harvard. “Solutions are going to be effected by our community coming together agreeing that this is a problem, that these aren’t just occasional isolated incidences or the rare bad apple, but something that we need to systematically address with culture-change.”

You can listen to the full interview with Kate Clancy, Robin Nelson, Julienne Rutherford, and Katie Hinde below:

This episode of Inquiring Minds, a podcast hosted by neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas and best-selling author Chris Mooney, also features a short interview with University of Chicago geoscientist Ray Pierrehumbert, who argues that we’ve been worrying too much about methane emissions from natural gas, and a discussion of a study finding that kids’ drawings at age four are an “indicator” of their intelligence 10 years later.

To catch future shows right when they are released, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes or RSS. We are also available on Stitcher. You can follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook. Inquiring Minds was also recently singled out as one of the “Best of 2013” on iTunes—you can learn more here.