<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=160526636&src=id">hohhew</a>/Shutterstock

This story originally appeared in Grist and is republished here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Republicans, as everyone knows, hate taxes and don’t accept, much less care about, climate change. But wonks on both sides of the aisle fantasize that a carbon tax could win bipartisan support as part of a broader tax-reform package. A carbon tax could be revenue neutral, the dreamers point out, and if revenue from the tax is used to cut other taxes, it shouldn’t offend Republicans—in theory.

And so people who want to bring Republicans into the climate movement like to argue that the GOP could come to embrace a carbon tax. We’ve heard it from former Rep. Bob Inglis (R-S.C.), who lost his seat to a Tea Party primary challenger in 2010 after he proposed a revenue-neutral plan to create a carbon tax and cut payroll taxes. We’ve heard it from energy industry bigwigs like Roger Sant, who recently argued the case at the Aspen Ideas Festival. We’ve heard it from GOP think tankers like Eli Lehrer.

It’s the epitome of centrist wishful thinking. It will not happen.

I know because I asked the man most responsible for setting Republican tax policy: Grover Norquist. As head of Americans for Tax Reform, Norquist has gotten 218 House Republicans and 39 Senate Republicans to sign his “Taxpayer Protection Pledge” never to raise taxes. His group has marshaled the Republican base’s zealous anti-tax activists and successfully primaried politicians who violate the pledge, making Norquist a much-feared and much-obeyed player in D.C. The Boston Globe Magazine went so far as to call him “the most powerful man in America“—at least of the unelected variety.

First off, Norquist has no interest in a carbon tax because, he told me, there has been no global warming for the last 15 years. That right-wing shibboleth is false, but the point is that if you don’t accept climate science, as Norquist and the Republicans don’t, you’ve got no reason to back a carbon tax.

Although Norquist conceded that you could theoretically construct a revenue-neutral carbon tax that does not violate his pledge, he would still oppose it, and he said Republicans generally would too. “I would urge people not to [vote for a carbon tax], because the tax burden is a function of how many taxes you have,” Norquist said, noting that higher-tax jurisdictions tend to have more sources of tax revenue. “With one tax, people can see how big it is. Divide it and no one knows.”

“I don’t see the path to getting a lot of Republican votes,” he concluded. Neither do I.

It’s useful to look at how Republicans react to other tax-reform ideas: Eliminate the carried-interest loophole that taxes hedge-fund managers at a lower rate than their secretaries? No way! Eliminate deductions for oil and gas companies? Nothing doing.

The arguments Republicans make about this one tax being unfair or that one stifling economic growth are all just arguments of convenience. Republicans are for taxing the things they don’t care about (poor people’s meager earnings) and against taxing the things they do care about (rich people’s unearned income). So Republicans oppose taxing inheritances and capital gains, but seem not to mind flat taxes on income or sales. That’s why the big tax-reform proposals that insurgent Republican candidates have ridden to prominence—Mike Huckabee’s “Fair Tax,” Herman Cain’s “9-9-9” plan—involve shifting much of the tax burden to a national sales tax: because sales taxes fall disproportionately on poor people. (Poor people have to spend a bigger portion of their income than rich people do just to get by, so sales taxes are regressive.)

And that’s why offering to cut payroll taxes in exchange for creating a carbon tax won’t win a bunch of Republican votes. First of all, Republicans don’t care about the tax burden on poor people, so the payroll tax deduction is not going to entice them. (In fact, they opposed an extension of President Obama’s payroll-tax holiday.) Meanwhile, they don’t share the premise that fuel consumption and carbon pollution are bad, because they don’t accept climate science. And they don’t want to shift the tax burden to fossil fuel companies, which are huge GOP contributors.

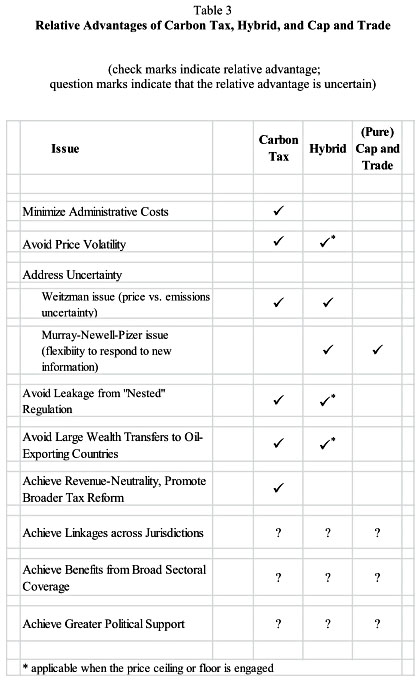

It’s worth remembering how a carbon tax became the ostensible bipartisan solution to climate change. Back in 2008, both parties’ presidential candidates backed cap-and-trade plans. Obama won and advanced his plan, so Republicans all opposed it. By default, whatever Obama proposes becomes “partisan” and the alternative becomes supposedly the reasonable, non-ideological idea Republicans would have supported. It’s always a lie.

There are two possible paths to either cap-and-trade or a carbon tax: One, Democrats gain control of both houses of Congress and the White House, and feel more pressure to address climate change than they did in 2010, when they let the opportunity slip away. Or, two, Republicans come to accept climate science and decide they want to save the world from burning. But until Republicans come around to acknowledge the reality of climate change, they’re not going to agree to a carbon tax.