This story originally appeared in Slate and is republished here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

If you’ve ever wanted to make post-stuffing snow angels, this year could be your chance.

Forget for a moment that Monday will feature near-record highs on the East Coast. (However, if you’re in Washington or New York City, you should bask in this afternoon’s highs in the low to mid-70s, if you can swing it.)

Forget, too, that in my post on Friday I said not to worry (yet) about a looming Thanksgiving Eve nor’easter. At the time, weather models were all over the place, with only the ECMWF showing a direct hit. Some models didn’t show a consolidated storm forming at all, just two separate weak weather systems: a minor storm over the Great Lakes and a stalled-out cold front somewhere between the East Coast and Bermuda.

Since then, there’s been growing consensus among the computers that those two systems will join forces. The National Weather Service has already posted winter storm watches for hefty snow totals just inland of the major Northeast cities along I-95. This storm is happening. And there’s an increasing chance it’ll force a change in your travel plans.

For instance, Sunday’s edition of the GFS model showed explosive storm formation on Wednesday—enough to qualify as a meteorological “bomb,” which is a deepening of the storm’s central pressure by more than 24 millibars in 24 hours.

31 mb / 24 hrs = “bombogenesis” or explosive cyclogenesis or “bomb” as Nor’easter rapidly develops of East Coast GFS: pic.twitter.com/2mVpte406m

— Ryan Maue (@RyanMaue) November 23, 2014

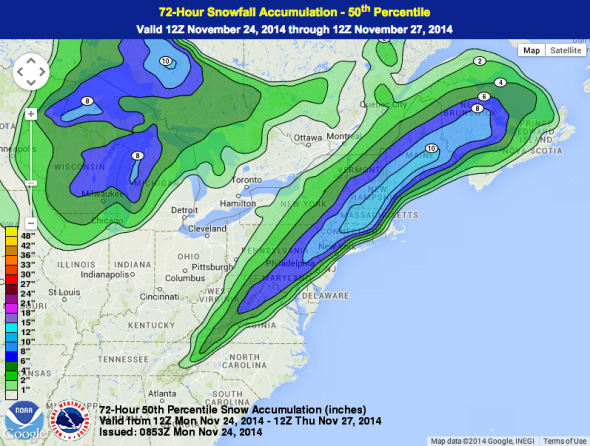

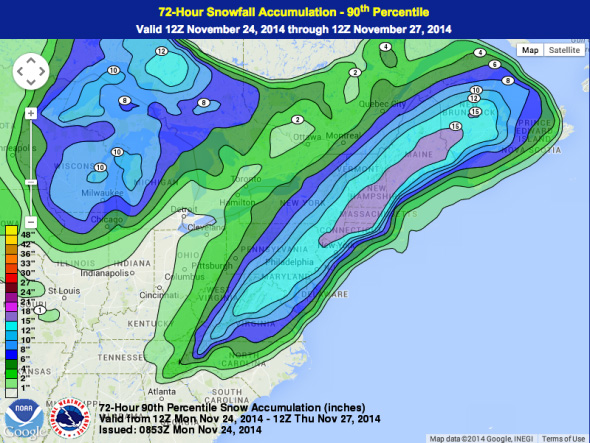

As the storm grows—starting off the mid-Atlantic on Wednesday morning and heading over Newfoundland on Thanksgiving afternoon—it’s now a lock to produce heavy snows well inland and in higher elevations from North Carolina to Canada. The only real question remaining is, how much snow will fall in the major cities along the coast?

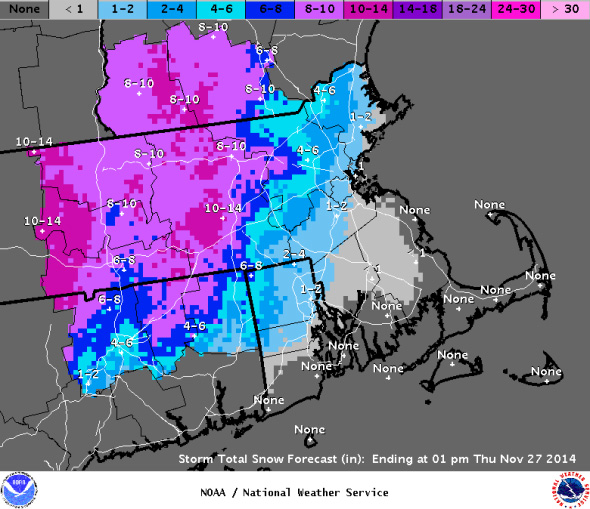

Even the National Weather Service can’t decide. The agency’s local forecast offices—the ones with the most knowledge of small-scale idiosyncrasies of tricky snowfall forecasts—are downplaying the storm’s potential to produce snow in the cities.

Here’s the local snowfall map from the Boston office, for example:

On the low end, that means this storm will bring only an inch or two of messy slush to the major cities, while Grandma’s house upstate gets the bulk.

The agency’s centralized forecast office—the Weather Prediction Center—is much more bullish.

In a reasonable worst case put forward by the WPC, 10 to 12 inches could fall in every major city from D.C. northward, snarling traffic and canceling flights coast to coast. A more reasonable guess is 3 to 6 inches of snow in the major cities, with double that just 30 miles inland. But even that outcome is just a blend of two extremes. The most likely scenario is a sharp cutoff between heavy cold rain mixed with a few flakes, and an all-out snowstorm. All the local forecast offices mentioned this annoying feature in their discussions on Monday.

There are still a few key unknowns, like the exact path the storm’s center will take offshore, that will determine which possibility becomes reality. Ocean temperatures are still in the 50s, so even an hour or two of wind from a northeast direction rather than due north could warm the lower levels of the atmosphere enough to turn snowflakes into raindrops along the coast. Dynamical cooling—which happens when a storm strengthens at quick enough rates—could help tip the scale toward coastal snow.

It would be just the second white Thanksgiving in New York City since 1938. The last one was in 1989, when the snowstorm’s strong winds tore a hole in Snoopy’s nose. In Washington, D.C., the storm promises an end to the longest November snowless streak since recordkeeping began in 1888. The last measurable snow during November in the nation’s capital was in 1996, when a piddly quarter-inch fell. There was also a big Thanksgiving Eve storm just last year, but no snow fell in either city.

In many ways, this is a weather forecaster/masochist’s dream scenario: You’ve got a potentially high-impact weather event, on the highest-impact travel day of the year, with an unusually high amount of uncertainty. To my fellow forecasters: Good luck getting this one right!