Thanks to an ongoing severe drought, water levels are extremely low at southern California's Lake Piru. Ringo Chiu/ZUMA

California is in the middle of a really bad three-year drought that stretches across nearly the entire state. The drought has already wreaked havoc with the state’s agricultural sector, is expected to take a $2.2 billion bite out of the state’s economy this year alone, and shows no sign of relenting anytime soon.

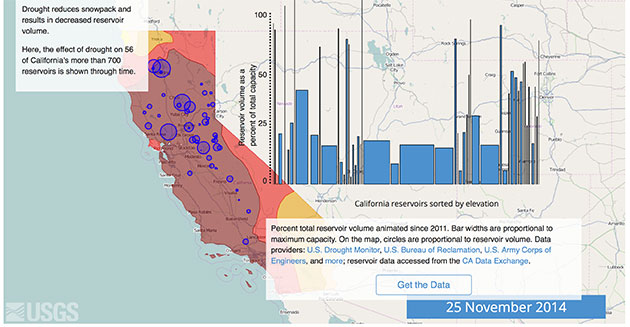

For a sobering, detailed look at the current state of affairs, take a look at the US Geological Survey’s just-released data visualization tool. The most shocking thing, to me, is the year-by-year playback of reservoir levels, many of which have now dipped to less than a quarter of their capacity (screenshot below):

Climate scientists have warned for years that rising greenhouse gas concentrations will lead to more frequent and severe droughts in many parts of the world. Although it’s generally very difficult to attribute any one weather event to the broader global warming trend, over the last couple of years a body of research has emerged to assess the link between man-made climate change and the current California drought. There are signs that rising temperatures (so far, 2014 is the hottest year on record both for California and globally) and long-term declines in soil moisture, both linked to greenhouse gas emissions, may have made the impact of the drought worse.

But according to new research by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, California’s drought was primarily produced by a lack of precipitation driven by natural atmospheric cycles that are unrelated to man-made climate change. In other words, climate change may have worsened the impacts of the drought, but it isn’t the underlying cause.

“The preponderance of evidence is that the events of the last three winters [when California gets the majority of its precipitation] were the product of natural variability,” said lead author Richard Seager, a Columbia University oceanographer.

Over the last three years, Seager said, unpredictable atmospheric circulation patterns, combined with La Niña, formed high-pressure systems in winter over the West Coast, blocking storms from the Pacific that would have brought rain to California. The result has been the second-lowest three-year winter precipitation total since record-keeping began in 1895. But that pattern doesn’t match what models predict as an outcome of climate change, said Seager. In fact, the study’s models indicate that as global warming proceeds, winter precipitation in California is actually predicted to increase, thanks to an increased likelihood of low-pressure systems that allow winter storms to pass from the ocean to the mainland.

Unusually high sea-surface temperatures in parts of the Pacific over the last two years also played a minor role in producing the observed high-pressure systems, the report found. But those anomalies were scattered, which is inconsistent with the uniform, general ocean surface warming expected as an impact of climate change.

As a result, the confluence of atmospheric and ocean conditions that have recently blocked rain in California look like an exception to, rather than representative of, the expected climate change trend, Seager said.

All this doesn’t mean you should dismiss the risk of future droughts: Seager stressed that additional research is needed to determine whether increased temperatures on land—leading to increased evaporation and demand on water supplies—could offset future gains in California’s winter rainfall.