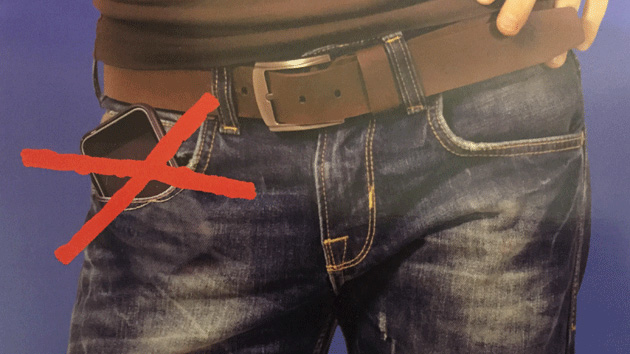

An image distributed last night by activists in support of Berkeley's cellphone right-to-know lawEnvironental Health Trust

UPDATE: On September 21, Federal District Court Judge Edward Chen gave the City of Berkeley a green light to implement its “right to know” cell phone law after deleting one sentence from its safety notification. The court struck the line, “This potential risk is greater for children.”

The City Council of Berkeley, California last night unanimously voted to require electronics retailers to warn customers about the potential health risks associated with radio-frequency (RF) radiation emitted by cellphones, setting itself up to become the first city in the country to implement a cellphone “right to know” law.

“If you carry or use your phone in a pants or shirt pocket or tucked into a bra when the phone is ON and connected to a wireless network, you may exceed the federal guidelines for exposure to RF radiation,” the notice, which must be posted in stores that sell cellphones, reads in part. “This potential risk is greater for children. Refer to the instructions in your phone or user manual for information about how to use your phone safely.”

The ordinance is widely expected to face a robust court challenge from the Cellular Telephone Industries Association, the wireless industry’s trade group. The law “violates the First Amendment because it would compel wireless retailers to disseminate speech with which they disagree,” Gerard Keegan, CITA’s senior director of state legislative affairs, said yesterday in a letter to the council members. “The forced speech is misleading and alarmist because it would cause consumers to take away the message that cell phones are dangerous and can cause breast, testicular, or other cancers.”

Cellphones emit non-ionizing radiation in the form of electromagnetic fields (EMF) that can penetrate human tissues. Although ionizing radiation, the kind used in x-rays, is known to cause cancer, the National Cancer Institute says there is no evidence that non-ionizing radiation increases cancer risk. The American Cancer Society calls the evidence for a cellphone-cancer link “uncertain.” The federal Centers for Disease Control maintains that “we do not have the science to link health problems to cell phone use.”

Some long-term epidemiological studies, however, have shown correlations between heavy cellphone use and cancer. In 2011, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classified radiation from cellphones as “possibly carcinogenic to humans.” Although the finding was hardly earth-shattering (pickled vegetables and coffee also fall into that category), concerns about the health effects of cellphones continue to mount.

A Turkish study published earlier this year, for example, found that the closer that the source of cellphone radiation was to breast cancer cells, the greater the damage to the underlying cells. The radiation increased the number of reactive forms of oxygen (a.k.a. free radicals), which can damage cells and have been shown to contribute to cancer development.

The Berkeley vote comes a day after an open letter from 195 scientists from 39 countries raised “serious concerns regarding the ubiquitous and increasing exposure to EMF generated by electric and wireless devices.” The scientists, among them researchers from the University of California-Berkeley, Columbia, and Harvard, called on government agencies to impose “sufficient guidelines to protect the general public, particularly children who are more vulnerable to the effects of EMF.”

Berkeley isn’t the first government to ponder a cellphone right-to-know law. According to CBS reporter Elizabeth Hinson, California, Hawaii, New Mexico, Oregon, and Pennsylvania have also considered requiring warnings, and legislation is awaiting a vote in Maine. In 2010, San Francisco passed a ordinance that would have required manufacturers to disclose each phone’s Specific Absorption Rate (the amount of RF energy absorbed by the body), but abandoned it a year later after losing the first round of a legal challenge by CTIA.

The Berkeley law is more narrowly tailored. “This ordinance is fundamentally different from what San Francisco passed,” Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig, who helped draft the Berkeley law, told the council at last night’s meeting. He has offered to defend the measure in court pro bono. “San Francisco’s ordinance was directed at trying to get people to use their cellphones less. This ordinance is just about giving people the information they need to use their phone the way it is intended.”

Safety tests mandated by the Federal Communications Commission, which regulates radiation levels in communication devices, assume that users will carry cellphones at least a small distance from their bodies in holsters. Storing phones in pockets or bras may expose users to RF heating effects that exceed FCC guidelines. For this reason, the FCC requires phone companies to disclose the minimum distance from the body that users should carry their phones—yet these guidelines are typically buried deep inside phones’ menus and sub-menus, or in the fine print of user manuals.

A survey conducted in April by the California Brain Tumor Association found that 70 percent of Berkeley adults did not know about the FCC’s minimum distance rule. And 82 percent said they wanted more information about it. (EMF activists have compiled the published separation distances for many cellphones.)

Berkeley passed the cell phone right-to-know law. One EMF activist took a celebratory photo with an iPhone6. It was on airplane mode.

— Josh Harkinson (@JoshHarkinson) May 13, 2015

Berkeley has a long history of imposing landmark regulations on powerful industries. In 1977, it became the first American city to ban smoking in restaurants. Last fall, it imposed the nation’s first tax on sugary beverages. The cellphone ordinance “is a crack in the wall of denial,” says Joel Moskowitz, director of the Center for Family and Community Health at the University of California-Berkeley, who testified in support of the law. “Look at what happened in 1977 with Berkeley’s smoking law: Things looked pretty bleak, but that led to a national movement.”

Moskowitz spoke to me in the hallway outside the council chambers, where EMF activists wearing “Right to Know” buttons were celebrating their win. Devra Davis, an epidemiologist and the author of Disconnect: The Truth About Cell Phone Radiation, asked me to snap a photo of her with Moskowitz on her iPhone 6. She’s not the kind of person who winces every time she gets a text, but she handles her phone with caution. “If I carry it on my body it’s on airplane mode, like it is now, or it’s off,” she said. “If it’s on, I put in the outer pocket of my fanny pack.”