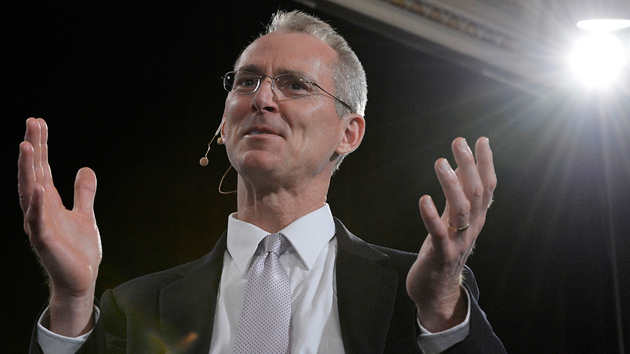

Former Rep. Bob Inglis (R-S.C.) in 2013. <a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/canada2020/8664418528/in/photolist-8uNQKo-8uKMLK-8uNPLJ-8uNPNs-8uNQYG-8uKNiK-8uKLGt-8vgTKg-8uNQH9-8uKLt6-8uKKTx-8uKLDc-8uNR1o-8uKLBc-8uKNav-8uNPk3-8uKMkt-8uKN4r-8uNPX9-6qHL8n-6qMYvQ-6qMUqC-5dAopt-6qHKsg-6qHLEt-5dW1Au-eAcpxX-6qMTHm-6qHS7x-6qHP1e-6qMSAf-6qN3D7-6qMZDA-6qMVg7-6qN2yo-6qMRF7-6qHPD6-6qN5r1-6qHMQ6-6qHJN2-5dRFmz-5dRFpp-5dW1qC-5dW1ob-ecDpLm-ecxLsK-8JHycE-5nokrB">Canada 2020</a>/Flickr

This story originally appeared in Slate and is republished here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Conservative climate champions are often laughed off or ignored. But what’s happening within the American political right could change everything, and fast.

Each year since 1989, the JFK Library bestows its Profile in Courage award to a public servant who takes a principled but unpopular position. This year, the award went to Bob Inglis, a former congressman from South Carolina who’s turned into America’s best hope for near-term climate action. Oh, he’s also a Republican.

As you might expect, Inglis wasn’t always a climate campaigner. In his acceptance speech last week at the JFK Library in Boston, he described how and why he changed his mind on global warming:

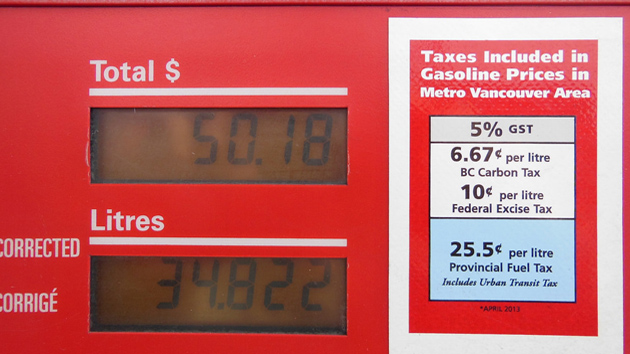

Inglis served in Congress for 12 nonconsecutive years, but once his children reached voting age, they persuaded him to take a closer look at climate science. Inglis traveled to Antarctica—twice—and his conversations with scientists there convinced him climate change was a growing threat that everyone, especially conservatives, needed to take more seriously. Science, plus his deep Christian faith, convinced Inglis that taking action on climate—and saving countless lives in the process—was the right thing to do. Almost immediately, he began advocating for carbon pricing: He argued that it would be good for business and the environment. He even began looking to Canada for inspiration. Since 2008, the government of British Columbia has had in place arguably the most successful climate policy on the planet. During a 2009 speech on the House floor, he called an American plan for a British Columbia–style revenue-neutral carbon tax a “fabulous opportunity.”

But his belief in the science of climate change became a liability for Inglis during the contentious 2010 primary election—an election associated with the rise of the Tea Party brand of ultraconservatism—and Inglis lost his seat in a landslide.

Since then, Republican views on climate change have inched ahead, and Inglis has made it his mission to spread the word: Protecting our planet is the ultimate bipartisan issue. “My grandfather’s legacy is kept alive by Bob’s courageous decision to sacrifice his political career to demand action on the issue that will shape life on Earth for generations to come,” said JFK descendant Jack Schlossberg, who presented the award to Inglis.

This is the point at which progressives and climate hawks might understandably get a bit cynical. But hear me out: For years now, the Republican electorate has been shifting toward accepting the scientific consensus on climate change. A recent survey showed moderate Republicans—which still make up about half of all Republican voters—are now essentially indistinguishable from the general population in terms of their beliefs on climate. More than 70 percent of Republicans now believe that human activities are contributing to global warming.

Most importantly, there’s recent evidence—and a few case studies—that point toward the root of Republican hostility toward climate action as mostly a matter of disliking the solutions on the table. That’s helped the fossil fuel industry fund a load of anti-science rhetoric and propelled climate change into the nation’s most divisive political issue. An optimist might say all that’s needed is a climate-action proposal that conservatives can get excited about.

That’s where Inglis comes in.

Essentially, Inglis is proposing cover for Republicans to vote for a price on carbon by offsetting any revenue it produces with equal or greater cuts in corporate taxes and personal income taxes. Such a proposal might turn the United States—which currently has among the highest business taxes in the world—into a tax haven and help drive economic growth. It could be tricky to pull off, but if done the right way, it would probably be popular with almost everyone and be an efficient way of tackling climate change.

In the meantime, there’s a huge gap between opinion polls and how Republican politicians vote on climate—and maybe between Republican politicians’ private beliefs and public actions. In 2013 Inglis told This American Life that he believes we could pass meaningful legislation today if his former Republican colleagues were “allowed to vote their conscience on climate change.”

Last week, I spoke with Inglis to get a clearer idea of why he’s so hopeful that Republicans could actually pave the way for bold action on climate.

“Too often the environmental left presents only the danger and not the opportunity of climate change,” Inglis told me. “Of course it’s a danger—the science is very clear. But it’s also an incredible free-enterprise opportunity, because why do we have to be dependent on these stinky fuels? Why can’t we have cleaner air? Why can’t we have distributed energy systems that light up the world with more energy, more mobility, and more freedom? Why can’t we?”

Inglis attributes the polarization in American climate politics to the choice of words that climate advocates often use that evoke the danger associated with climate change and the implied judgment for denial and lack of action. “The problem with that is: Denial is a pretty good coping mechanism for threats like death,” he said.

Instead, Inglis thinks it’s time to be optimistic about climate change. He says the most exciting aspect of working for action on climate is the potential to “light up dark places in the world” with clean energy. That, when combined with a shift in rhetoric away from “doom and gloom” of the left, may be enough to persuade Republicans to get on board.

Inglis repeatedly invoked the idea that a bold plan to fight climate change could recapture a sense of the American exceptionalism that Kennedy exemplified in his moonshot speech at Rice University in 1961. In that speech, Kennedy said going to the moon was “an act of faith and vision,” but “we must be bold.” That’s exactly how Inglis feels about the need to tackle climate change: with uncertain technology, and uncertain political support, and uncertain science. “If you can put it in the context of opportunity and calling to light up the world, then you get that moonshot kind of optimism and determination,” Inglis said.

To quote a very underquoted line from President Kennedy’s speech at Rice, “I think we’re going to do it.” @bobinglis #climatechange

— JFK Library (@JFKLibrary) May 3, 2015

Inglis believes an American price on carbon could quickly motivate other large economies, like China and India. “We need the leading economy in the world to say, ‘We just priced carbon dioxide in our economy. We’re going to collect it if you’re shipping things in here. Now what are you gonna do?’ The rest of the world would then follow suit,” he said.

That’s why Inglis thinks a US carbon tax is more important than the UN Paris summit this December—which has a big profile but pretty unambitious goals.

His “most positive scenario” for near-term action on climate: a Republican president in 2016. That would set up a top-down push for Republican-led climate legislation, as long as the right candidate is elected, of course. He offered three possible names:

Lindsey Graham: According to Inglis, there are “some good things Lindsey has said and is saying about climate change.” I agree.

Jeb Bush: “I know from personal interaction with him that he’s a careful, analytical fella,” Inglis said. Bush recently broke with the pack, saying he was “concerned” about climate change.

Rand Paul: “[Libertarians] really believe in accountable, transparent marketplaces, and the energy marketplace is not transparent right now. They’re getting away with socializing their soot and passing to future generations the cost of climate change. That’s a market distortion,” Inglis said. With billions of dollars in subsidies to the fossil fuel industry each year, it’s not a stretch to suppose Paul would take the opportunity to reduce the size of government via a libertarian argument for climate action.

Now, Inglis may be a few years ahead of his time here, but it’s increasingly unfathomable that the Republican Party would nominate an out-and-out climate denier. Even though climate change isn’t yet a top-tier issue, voters are now less likely to vote for a candidate who opposes action to reduce global warming. In fact, every major demographic is in favor of regulating greenhouse gases, even if it causes an increase in their energy bills—except for Republicans over 65. As younger voters gain clout, Republican opposition to climate change among the electorate is fading.

Together with evangelical Christian climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe and the retired Navy Rear Adm. David Titley, Inglis represents the forefront of the American conservative zeitgeist on global warming. It’s interesting to note that they’re also all infectiously optimistic. Hayhoe, who’s in the midst of an indefinite speaking tour, primarily to conservative audiences, recently told me that when it comes to action on climate change among those on the right, “There is a dam effect. Once the dam is breached, there could be rapid change.”

After speaking with Inglis, I have to agree. It’s refreshing to hear anyone—especially a Republican—actually hopeful on climate. My wife and I had an hourslong conversation following the interview. Her main takeaway: “Why can’t more people think like him?”