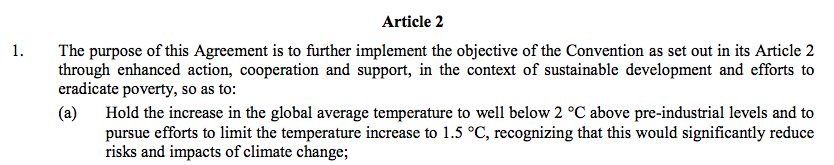

Update—December 10, 2015, 4:50 pm ET: Delegates in Paris appear to have agreed on Thursday to “pursue efforts” to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit)—a target that US negotiators had been pushing for. That’s substantially less warming than the 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) limit that was agreed to in Copenhagen in 2009. Here’s the latest text from Thursday evening’s draft agreement:

However, the document also “notes with concern” that the actual actions that countries have so far agreed to take to reduce their emissions fall well short of both the 1.5 degrees C target and the 2 degrees C limit.

Original story:

The international climate summit in Paris may be getting too ambitious for its own good.

There are a lot of numbers flying around at Le Bourget, the modified airport in a northern Paris suburb where diplomats from around the world are racing toward an unprecedented international agreement to limit climate change. Many of the most important are dollar figures: the need for wealthy countries to raise $100 billion annually to help vulnerable countries deal with climate impacts, and promises by the United States to double spending on clean energy research and climate adaptation grants for developing countries.

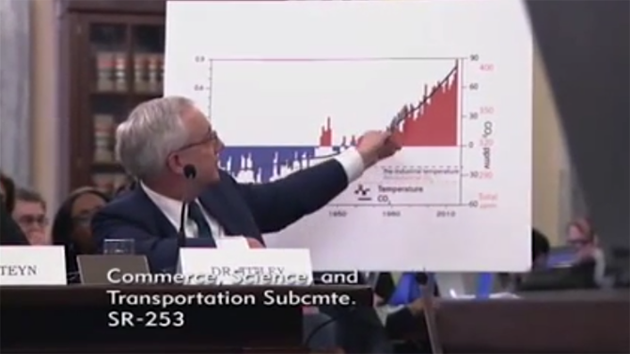

But right at the top of the draft agreement is another number that, in the big picture, could be the most important. That’s the overall limit on global temperature increase that the accord is designed to achieve. At the last major climate summit, in 2009 in Copenhagen, world leaders agreed to cap global warming at 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, based largely on findings from scientists with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that anything above that level would be totally catastrophic for billions of people around the world, from small island nations to coastal cities such as New York.

All the other moving pieces in the agreement, which officials here hope to conclude by late Friday or Saturday, are more or less aimed at achieving that target. It’s the number that is really driving the sense of urgency here, since earlier this year the world crossed the halfway point toward it. In other words, time is running out to keep climate change in check.

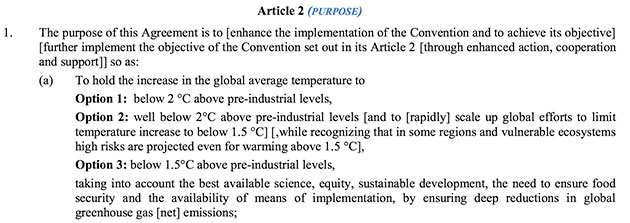

As the negotiations push into their final hours, something unexpected is unfolding: That target might actually get even more ambitious. There’s a very good chance, analysts and diplomats say, that the final agreement will call for a limit of 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit)—a crucial half degree less global warming. Here’s the relevant section of the text; negotiators need to pick one of these options:

The US delegation is supporting Option 2, according to an official in the office of Christiana Figueres, the head of the UN agency overseeing the talks, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the official is not authorized to speak to the press about the negotiations. That aligns with the announcement, made yesterday by Secretary of State John Kerry, that the United States will join the European Union and dozens of developing countries in the so-called “High Ambition Coalition,” a negotiating bloc that has emerged to push for the strongest outcome on several key points, including the temperature limit.

Negotiators in that bloc have realized, the official said, that “if they move the long-term goal further out, it will move politics in the short term closer to where they need to be.”

If the 1.5 degrees C target makes it into the final agreement, that would be a massive win for climate activists and delegates from many of the most vulnerable nations, especially the small island nations. Since the 2 degrees C goal was set in Copenhagen, the leaders of low-lying countries like the Marshall Islands and the Maldives have increasingly protested that even that level of warming would essentially guarantee the destruction of their islands.

The fact that the United States is now backing a more ambitious target is a sign that President Barack Obama is hearing that message, said Mohamed Adow, a Kenyan climate activist with Christian Aid.

“Paris is meant to indicate the direction of travel, and the US giving in on this point demonstrates their solidarity,” he said. “You’re talking about a level of warming that we can actually adapt to.”

But here’s where things get problematic. There’s a huge difference between including the 1.5 degrees C limit in the agreement, and ensuring that it could actually be met. That’s because other key pieces of the agreement that could actually make that level of ambition possible are still far from clear. The biggest obstacle could be the hotly debated “ratchet mechanism,” which would require countries to boost their targets for greenhouse gas reductions over time, and which the US delegation appears to be resisting. The current draft of the text includes language directing countries to provide an update of their progress every five years or so, which would be compiled into a global “stock-take,” a kind of collated update, sometime after 2020. But the enforcement stops there; there’s nothing in the agreement to penalize countries that lag behind or to compel them to boost their ambitions. Yesterday, Kerry offered a confusing take on that problem when he said that in the agreement, “there’s no punishment, no penalty, but there has to be oversight.”

Everyone here seems to agree that Paris is only a starting place: Without an incremental ramping-up of climate goals, 2 degrees C—not to mention 1.5—will remain out of reach. The current set of global greenhouse gas reduction targets only limit global warming to roughly 2.7 degrees C (4.9 degrees F). That’s a big gap.

“It’s not looking good,” Adow said. “If the US means business, are true to their support, they need to agree to an annual review starting in 2018.”

Instead, it seems that the United States could be trading a concession on the 1.5 degrees C target for steadfast resistance to increasing its funding for climate adaptation in developing countries. The United States is also standing in the way of a “loss and damage” component, which would require heavily polluting countries to compensate countries that have been wracked by climate impacts. Without extra money on the table to invest in clean energy, developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere won’t be able to contribute to the 1.5 degrees C target, said Victor Menotti, executive director of the International Forum on Globalization, a San Francisco-based activist group.

“The US is pretty clear they want 1.5,” he said. “The question is what’s going to accompany it, and at what price. They’ll be able to claim climate leadership, but without any means of implementation.”

The upshot is that the whole Paris accord risks losing credibility if it comes up with a really ambitious target and no way to reach it. All of these pieces are essential, because even with the best possible outcome in Paris, 1.5 degrees C is going to be really hard to meet, said Guido Schmidt-Traub, executive director of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. In a recent report, Schmidt-Traub found that meeting the 2 degrees C limit means ceasing all greenhouse gas emissions worldwide by 2070. And because most coal- and natural-gas-fired power plants have multidecade lifespans, that means we need to start planning to cease building them as soon as possible.

“The bottom line is that 2C requires all countries to decarbonize their economy at a very rapid rate, but in our analysis there is some wiggle room,” he said. “If you go to 1.5C, it becomes very hard to have any wiggle room left. This is a very fundamental point that is not being discussed at all in the negotiations.”