photojournalis/iStock

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The United States and China are leading a push to bring the Paris climate accord into force much faster than even the most optimistic projections—aided by a typographical glitch in the text of the agreement.

More than 150 governments, including 40 heads of state, are expected at a symbolic signing ceremony for the agreement at the United Nations on April 22, which is Earth Day.

It’s the largest one-day signing of any international agreement, according to the UN.

But leaders will really be looking to see which countries go beyond mere ceremony and legally join the agreement, which would bind them to the promises made in Paris last December to keep warming below the agreed target of 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit).

So far, the US, China, Canada and a host of other countries have promised to join this year—boosting the hopes of bringing the Paris deal into force before the initial target date of 2020—possibly as early as 2016 or 2017, according to officials and analysts.

That is well before the timeline originally envisaged at Paris. Environment ministers attending the World Bank spring meetings this week said the faster pace indicated serious commitment to dealing with the global challenge.

The accelerated timeline would have one obvious advantage for Barack Obama. The standard withdrawal clause on any such agreement would force a future Republican president to wait four years before quitting Paris, according to legal experts.

An earlier start date could also turbo-charge the agreement, providing momentum for deeper emissions cuts.

It could also help efforts to attain the more ambitious goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C (2 degrees F)—which would give a better chance of survival to small islands and other countries on the front lines of climate change.

Christiana Figueres, who heads the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, has said global emissions need to peak by 2020 to have any chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C. There has already been about 1 degree C (1.8 degrees F) of warming above pre-industrial levels.

“Early entry into force—we are very committed to making that happen,” Catherine McKenna, Canada’s environment and climate change minister, told a panel at the World Bank last week. “We can’t just now rest on our laurels and have a nice signing on Earth Day, and then we all go home.”

She told the Guardian Canada was committed to signing the agreement this year.

The push to bring the climate agreement into force quickly is in sharp contrast to the earlier international efforts to fight climate change through the Kyoto Protocol, which did not take effect for four years.

Eliza Northrop, an analyst at the World Resources Institute, said there was growing momentum behind an early approval of the agreement.

“It’s likely it could come into effect in 2017. It could even happen this year,” she said.

Governments at the Paris climate meeting had initially set the start date of the agreement in 2020—with intense discussion over whether that start date should be at the start or end of the year, according to diplomats.

The 2020 date remained in the negotiating drafts almost until the very end, the diplomats said. But unaccountably the final draft prepared by France left out the entire clause. By that point, after a few late-night negotiating sessions, a number of countries did not notice the omission.

The agreement, the first time all countries agreed to emissions cuts and other actions to fight climate change, aims to limit warming to below 2 degrees C and move towards a zero-carbon economy by the end of the century.

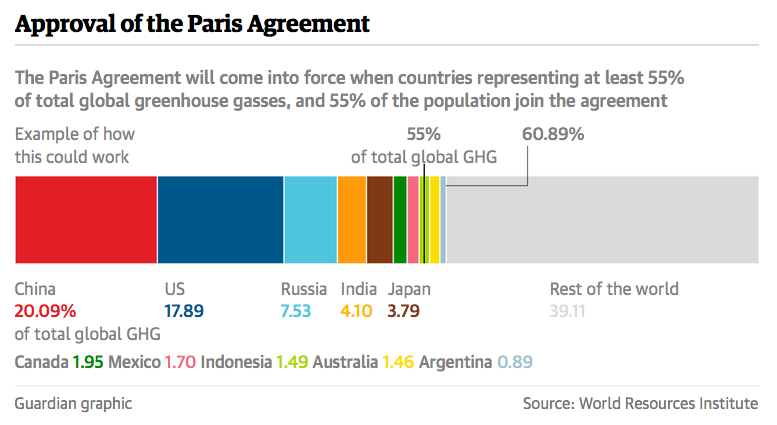

But it’s a tall order. The agreement needs to be approved by 55 countries accounting for at least 55 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions to come into force.

The US and China committed to join the agreement this year—but that still leaves a gap of more than 15 percent of global emissions.

A number of countries, including India and Japan, require their parliaments to approve the Paris agreement—a process which could take time.

The European Union will need agreement from its 28 member states before it can join the agreement—which makes it highly unlikely to be in a position to join early on.

“The assumption is that you have to do this without the EU to get to that 55 percent hurdle, if you want to see that in the next year or so,” said Alden Meyer, strategy director for the Union of Concerned Scientists.

That will force governments to cobble together a coalition of smaller countries if they hope to reach the 55 percent emissions threshold.

Possible contenders include India, Mexico, the Philippines, and Australia.

So far, about 10 countries have said they would join the agreement this year.

On Wednesday, Román Macaya, Costa Rica’s ambassador to Washington, said his country would join the agreement in 2016. Palau, Switzerland, Fiji, and the Marshall Islands have also said they will approve the agreement this year.