The image of a lonesome tumbleweed rolling across the plain is synonymous with the American West. But in eastern Colorado, tumbleweeds have become annual invaders, blocking roads and even burying houses. The infestations have been made worse by drought and climate change. The best way to get rid of them is heavy machinery—and the internet. Tumbleweeds sell online as home decorations for between $15 and $30.

We talked with photographer Theo Stroomer who has spent the past three tumbleweed seasons (fall to spring) documenting this peculiar menace.

Mother Jones: Why are there so many tumbleweeds? Is the problem getting worse?

Theo Stroomer: This has been a problem periodically in the past, though I do believe it’s more common nowadays. This article suggests that a town in South Dakota got buried in 1989, which is the earliest I’ve heard of it happening. There are many species of tumbleweed. A rough definition would be a plant that grows, dies, breaks off from its roots, and spreads its seeds as the wind blows it around. What they all have in common is an uncanny ability to grow in dry conditions and reproduce like crazy. Drought plays to their strengths, suppressing the growth of other plants. So as drought gets more severe, we are likely to see more problems with tumbleweeds. In Colorado, in particular, we have created an ideal situation for tumbleweed growth because much of the eastern plains—counties like Crowley—have sold their water rights to urban areas. Without agriculture or moisture, there’s a lot of empty land available for takeover. 5280 Magazine did a great write-up by Robert Sanchez (with photos by [Mother Jones contributing photographer] Matt Slaby) addressing this.

MJ: How did you first hear about these tumbleweeds, and how much of a nuisance are they for residents?

TS: I started hearing about this stuff in early 2014. My friend Sarah Gilman, a reporter, mentioned offhand that she was writing a small piece about Colorado towns getting buried in tumbleweeds. It sounded perfect for a visual approach, so I started poking around and eventually decided I wanted to do a project.

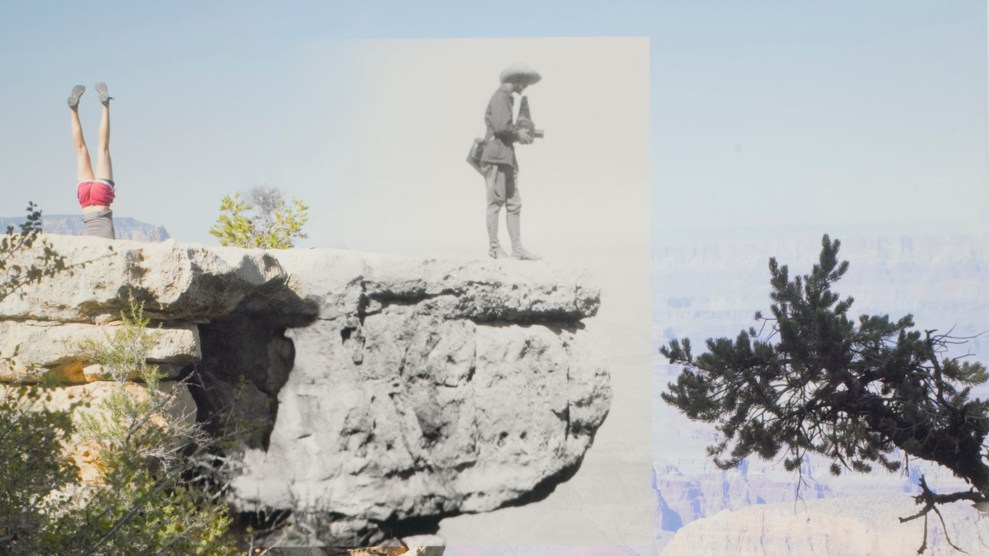

At first, I was focusing on tumbleweed attacks as a way to talk about drought and climate change. Over time, an added dimension crept into the work: I realized that this plant has won a measure of acceptance as it puts down roots in the communities it calls home. That’s where all the weird cultural stuff comes in.

As for the nuisance level, it varies significantly by year and location. I end up in many communities with folklore about that one time when the tumbleweeds stormed through. I’m not aware of any places that have regular levels as high as you see in my photographs—those are isolated events, but they speak to a pattern that does seem to be occurring every year.

MJ: How do you find communities to photograph?

TS: I have ended up relying heavily on the internet and social media to figure out where I can make images. I get an email whenever “tumbleweed” shows up somewhere on the web, and I go looking for other people’s pictures of what is happening in their communities. That has led to many of my photos, as well as some things I doubt I’ll ever get to see in person, like a “tumbleweed fire tornado” just six miles from my house, that I missed.

As the research has branched out I’ve found other moonshots that aren’t likely to be feasible, such as (naturally) red tumbleweed gardens in Japan or a flammable tumbleweed fireplace log designed in Arizona that is held in a botanical collection in the UK.

MJ: Are there specific regions that get hit hardest by the tumbleweeds?

TS: It varies every year, but I know they can get bad in South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. Maybe a better way to think about it would be “what times are the tumbleweeds the worst?” and the answer is in times of drought. In my experience, the recipe for a tumbleweed attack is a lot of open ground, along with dry seasonal conditions that help tumbleweeds outcompete other plants. Once they’re dry and ready to break off, you need a few hours of 50 mph winds in the direction of a town.

MJ: Is there a long-term solution?

TS: I see reports occasionally that USDA researchers are testing a weed-eating fungus, but I think this is far from certain as a solution (or a good idea, without more information). Ultimately, I believe that tumbleweeds are an example of environmental change that we’re going to end up living with. Because there’s a dash of humor in the story, I hope that knowledge of these infestations makes it easier to have conversations about water use and drought and ultimately climate change.

MJ: How many tumbleweed events like the tumbleweed Christmas tree are there in the United States?

TS: I am only aware of three. Everything else is less formally organized, although people do seem to like building stuff with them.

- The Haigler, Nebraska, tumbleweed festival and decorating contest. (There are other tumbleweed festivals, but they don’t actually involve tumbleweeds, as far as I can tell.)

- Chandler, Arizona, erects a tumbleweed Christmas tree (not in this essay yet).

- Albuquerque, New Mexico, has an annual tumbleweed snow man (also not in the essay yet).

MJ: What’s the most creative thing you’ve seen done with the tumbleweeds?

TS: I’m fond of this installation, a collaboration between artists Julius Von Bismarck, Julian Charriere, and Felix Kiessling. I don’t know their work, but the website says they are young up-and-coming folks from Berlin.

MJ: How long do you think you’ll be working on this project? What’s the end goal?

TS: There’s a season, which is roughly late fall through early spring. 2016 to 2017 is my third season of photography. I wonder sometimes if tumbleweed attacks will become commonplace and fewer people will care, the way we treat snowstorms now. I’m still enjoying the work, but I don’t know if there are very many new pictures outside of the longshots I mentioned above. I’d like to do a book. I haven’t decided if I have a Kickstarter campaign in me, so I may stick to a small handmade edition. I am also working on turning this into an exhibit filled with actual tumbleweeds. Another goal would be to be on TV with the words “Tumbleweed Expert” scrolling underneath me while I talk.