Sullivan in his Los Altos officeCourtesy Peter Sullivan

Peter Sullivan and I are driving around Palo Alto, California, in his black Tesla Roadster when the clicking begins. The $2,500 German-made instrument resting in my lap is picking up electromagnetic fields (EMFs) from a nearby cell tower. As we follow a procession of BMWs and Priuses into the parking lot of Henry M. Gunn High School, the clicking crescendos into a roar of static. “I can feel it right here,” Sullivan says, wincing as he massages his forehead. The last time he visited the tower, he tells me, it took him three days to recover.

Sullivan is among the estimated 3 percent of people in California who claim they are highly sensitive to EMFs, the electromagnetic radiation emitted by wireless routers, cellphones, and countless other modern accouterments. Electromagnetic hypersensitivity syndrome—famously suffered by the brother of Jimmie McGill, the lead character on AMC’s Better Call Saul—is not a formally recognized medical condition in most countries and it has little basis in mainstream science. Dozens of peer-reviewed studies have essentially concluded that the problem is in peoples’ heads.

That’s what Sullivan used to think, too. A Stanford computer science major who has worked as a software designer for Excite, Silicon Graphics, and Netflix, he paid little mind to EMFs, which he once viewed as harmless and inevitable. His wife joined Google early on and now serves as its chief culture officer—founder Sergey Brin sometimes drops by the couple’s home sporting Google Glass. “I thought that anybody that talked about the health effects of EMFs was a complete idiot. I thought that they just were not science-y,” Sullivan recalls. But then he got sick.

Around 2005, Sullivan started having trouble sleeping. He lost weight precipitously and struggled to maintain focus. After his top-flight Stanford doctors failed to figure out what was wrong with him, he tried every alternative remedy on the books, from cutting out gluten to taking chelating agents to purge his body of heavy metals. Nothing really worked. He noticed, however, that he felt weird after talking on a cellphone or plugging into a laptop charger. So like any good health hacker, he kept debugging.

A feng shui consultant in Silicon Valley knew a guy in Los Angeles who called himself a “building biologist” and had reputedly worked wonders for Richard Gere. Sullivan flew the guy up to his $6 million home in a leafy Los Altos neighborhood and watched with interest as the man probed the baseboards of Sullivan’s newly renovated bedrooms, bulky instruments flashing and buzzing. The consultant’s verdict: Sullivan’s house was an EMF disaster zone. The wifi and cordless phones would have to go. He’d need to rip out the walls and change everything.

This was a bit like asking a winemaker to quit drinking or advising an auto exec to commute on a fixie. Sullivan took things slow at first, installing some metal shielding around the electrical conduits in his downtown Los Altos office to block a portion of the radiation. He subsequently found that a 30-minute catnap in his office left him more replenished than a whole night’s sleep at home, so he began napping there regularly. One day when he felt like the EMFs in his home were really messing with him, he drove up to a hiking trail in the Los Altos hills and slept in the parking lot.

By the time I met Sullivan in person, one bright day this past spring, he had regained the lost weight and was feeling good. A former Navy pilot who used to land fighter jets on aircraft carriers, Sullivan still has a military crispness in his posture and elocution. Having recently retired from tech at age 40, he now devotes most of his time to exposing the hazards of EMFs. He has even brought up the matter with a few high-ranking friends at Google. “This is the new smoking,” he recalls telling them. “It’s just like the beginning days, when the evidence is there and people aren’t catching on.”

Many controlled studies do, in fact, show that people who claim to suffer from electromagnetic hypersensitivity experience symptoms when exposed to electromagnetic fields. But if those same people are unaware that the EMFs are present, the correlation between the symptoms and the exposure evaporates. The leading explanation is what’s known as the “nocebo” effect—people feel sick when exposed to something they believe is bad for them. Case in point: In 2010, residents of the town of Fourways, South Africa, successfully petitioned for a cellphone tower to be removed due to a rash of illness in the area. It was later revealed that the tower wasn’t operational during the period of the complaints.

But don’t expect Jimmie McGill’s big brother to give up his space blanket just yet. Other research suggests that EMFs do have measurable biological effects, albeit in lab animals. A $25 million study released in May by the National Toxicology Program found that male rats exposed to radio-frequency radiation, the kind emitted by cellphones, were more likely to develop two forms of cancer—although the findings were controversial. Joel Moskowitz, the director of the Center for Family and Community Health at the University of California-Berkeley and a believer in electromagnetic hypersensitivity syndrome, argues that the wireless industry has used its financial clout to suppress essential health research. “This is very much like tobacco back in the 1950s,” he concurs. “The industry has co-opted many researchers and has stopped funding many people who were finding evidence of harm.”

Sullivan, who majored in psychology as an undergraduate, refuses to believe that he’s just being neurotic. Through his foundation, Clear Light Ventures, he has given about $1 million to anti-EMF advocacy groups and researchers that the wireless industry won’t touch. They include retired Washington State University biochemistry professor Martin Pall, who has proposed a biological mechanism for EHS, and Harvard neurology professor Martha Herbert, who has suggested there could be links between EMFs and autism.

Laura Torres, who worked with Sullivan in the early 1990s as a product manager at Silicon Graphics, remembers him as a guy who “totally thinks outside the box.” He created software to log customer service calls, then a novel invention and a big-time saver for the company’s tech support team. “He really takes a creative approach to solving problems, which I think is what he is doing with this EMF thing,” she says.

Sullivan says his anti-EMF advocacy should not be viewed as an affront to his fellow techies: “We are hoping that the industry, instead of being like tobacco and going through denial, will be more like the automotive industry and say, ‘Okay, we are just going to keep improving safety. We will sell you more stuff that is safer and lower power.’ And it will be a win for everybody.”

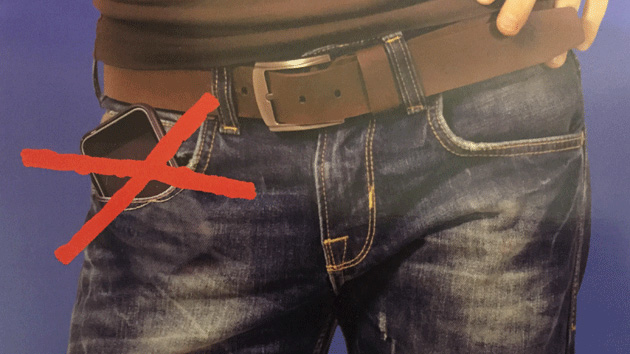

During my visit, Sullivan walks me through his home’s $100,000 worth of EMF-proofing. In his wood-paneled home office he points out a $1,000 Alan Maher technical ground, a device that helps channel electrical noise away from power outlets, and a plug-in Stetzer filter, which makes “a nice clean sine wave in your electricity,” as my host puts it. He flips a desktop switch to cut off power to his MacBook—he rarely works on it while it’s charging. He made an exception last night after the battery died and says he ended up feeling wired and jittery as a result.

We step outside and through a gate, crunching over groundcover to the shingled exterior of his first-floor bedroom. Sheets of black mesh hang from a nearby fence to block a neighbor’s wifi signal. A nearby power line is wrapped in a material that dissipates certain electrical frequencies as friction, like a string dampener on a tennis racquet. Sullivan has installed a switch by his bed that lets him shut off his home’s electricity while he sleeps. “Our bedroom is like camping!” he says proudly. “We have all the luxury of being inside, but none of the EMFs.”

Indoors on a kitchen stool his wife, Stacy, is hunched over a laptop plugged into an ethernet cable. “She’s in wireless jail,” Sullivan jokes.

“I used to be able to just do this wherever I wanted to work,” she responds wistfully. “But it’s okay.”

In terms of protection, this residence doesn’t even compare with another one Sullivan owns in the Los Altos hills. We hop in his Tesla (modified to shield him from its EMFs) and drive there. Originally built in the early 1900s as a hunting lodge, it had been renovated into a shrine to modernism by an HP executive. Sullivan bought it a few years ago and converted it into what he calls a “model healthy home.” He’s hoping its shielded environment will help me to understand what sudden exposure to EMFs feels like.

In an empty upstairs bedroom that Sullivan sometimes uses as an office, a graphite paint called WiShield coats the walls. Clear, EMF-blocking films cover the windows. Conductive tape on the floor carries any electrical current to a high-frequency ground in the closet. Sullivan switches on his EMF meter: zero. “I thrive on it!” he says. “I get my best work done here.”

He hands me a bottle of oxygenated water and instructs me to down it. This will supposedly unclump my blood, heightening my EMF sensitivity. Rummaging through the closet, he emerges with an air pump from his son’s aquarium. He has discovered that this pump maxes out his instruments, producing “a fucking nightmare magnetic field.” He holds it a couple of feet away from me and switches it on. I feel a small cramp in my stomach.

Maybe Sullivan was onto something. After all, birds and sea turtles use Earth’s magnetic fields to navigate, and foxes seem able to rely on them to detect prey. Then again, maybe all I’d felt was the nocebo effect. Sullivan suggested that I get to the bottom of it by spending a night at the shielded house. I didn’t feel the need, I told him, but I understood why he might. “When I wake up, it just feels like you can do anything,” he’d assured me. “You just feel completely different, like your world has changed.”