Cows graze on a Northern California pasture.

Several years ago, the California meat entrepreneur Bill Niman began applying an extremely old idea to his ranch on the Northern California coast: He would treat beef as a seasonal delicacy, only slaughtering cows fattened while the grass is lush and green, from late spring to fall. As my colleague Maddie Oatman noted in a 2013 piece, the practice harked back to a time before the rise of the modern corn-centered feedlot, which severed beef’s “tie to grass growth cycles,” Maddie wrote. When grass-based ranchers indulge the modern appetite for year-round beef by slaughtering hay-fattened cows in the winter, the meat is inferior in quality and taste, hurting grass-fed beef’s reputation, Niman argued.

Now, Niman is applying an up-to-the-minute idea to his old-school ranch: He has sold his operation to the meal-kit company Blue Apron. Niman will stay on as president of BN Ranch, now a subsidiary of Blue Apron.

The news stunned me. Blue Apron is a fast-growing company with $800 million in annual sales. Niman’s previous company, Niman Ranch, is a sizable producer—but Niman himself hasn’t been associated with it for years, and it’s now owned by chicken giant Perdue. “I left Niman Ranch because it fell into the hands of conventional meat and marketing guys as opposed to ranching guys,” Niman told Business Insider in 2014. “You can’t really ferret out how [the cattle] are being raised [now].” I had thought Niman’s new company, called BN Ranch, was a tiny niche operation, more suited to supplying Northern California foodie temples like Chez Panisse than providing fodder for a galloping “unicorn” (Silicon Valley-speak for a startup valued at $1 billion or more) that delivers more than 8 million meals per month.

Turns out, I was wrong about the new Niman company’s size. In a phone conversation, Niman explained that he has spent the past several years quietly scaling up BN Ranch using the same method he used during the original Niman Ranch’s ’90s/early 2000s heyday: by banding together with other ranchers along the West Coast who share his devotion to grass and seasonality, marketing their meat under the BN Ranch brand. In order to provide year-round product while sticking to his fresh-grass principle, Niman also sources from pasture-based ranches in New Zealand, which has a “perfectly complementary season to ours,” he said. Niman calls it “following the global grass seasons.” Niman said the butchered beef travels to the United States via boat, aging while en route, which he characterized as an energy-efficient process.

Niman says BN Ranch started supplying Blue Apron two years ago, and now provides the meal-kit company with half its beef. The goal, he said, is to eventually provide 100 percent. Niman plans to continue growing the beef business, not by scaling up production at his own ranch, but by bringing in more farms both in the United States and in the southern hemisphere. Niman says he visits the farms in the network often, including the one in New Zealand.

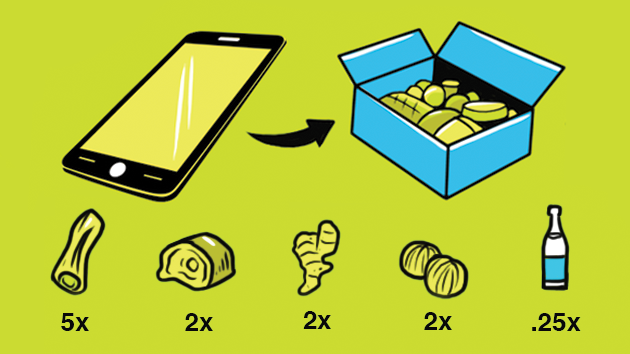

I asked him how Blue Apron can possibly pay its rancher-suppliers an attractive price while also covering costs, much less turning a profit, given the company sells meals at a rate as low as $8.74 per eater, and BN Ranch boneless rib eyes fetch $19.99 per pound retail. He said the relationship works for the meal-kit titan and for ranchers, because Blue Apron buys the whole cow at a fair price, and “writes menus around every part of the animal.” For the rancher, that’s a great set-up, because it removes the burden of marketing—for every $20/pound steak sold, a rancher has to market several more pounds of less fancy cuts. Blue Apron, for its part, gets access to top-quality beef at a much lower price point than it would get by buying individual cuts on the open market. And the variety of cuts works for a company that sends out as many as three recipes per week to millions of customers.

I left my conversation with Niman thinking the tie-up made sense. Yet I still have doubts about the meal-kit business model, which I aired here. In short, food businesses generally operate on razor-thin profit margins, and meal kits are no different. They don’t have the huge real estate expenses that restaurants do, but they face the pricey task of shipping millions of hand-packed boxes stuffed with small amounts of lavishly cosseted perishable goods across great distances. The price they charge customers may not sound cheap at first glance, but it seems punishingly so to me when you consider all those expenses. I wasn’t surprised last fall when workers at Blue Apron’s Richmond, California, packaging facility complained of tough conditions and low wages. Nor was I shocked in December, when Blue Apron delayed its much anticipated initial public stock offering, because the company “has struggled to improve profit margins as much as management wanted in the face of more competition,” as Bloomberg reported.

Yet Blue Apron’s big move into the grass-fed beef business does suggest confidence about the future.