Firefighters from across Kansas and Oklahoma battle a wildfire near Protection, Kansas, Monday, March 6, 2017. <a href="http://www.apimages.com/metadata/Index/Severe-Weather/33ad2b67f93c4651a4759380bbe40cab/17/0">Bo Rader</a>/The Wichita Eagle via AP

Sen. James Inhofe (R.-Oklahoma) is alarmed at what he accurately called the “unprecedented” wildfires now ripping through the grasslands of Oklahoma, Kansas, and the Texas panhandle. So far, the fast-moving fires have burned more than 2 million acres in the region, “causing millions of dollars of damage and killing thousands of livestock,” Reuters reports. At least seven people have died, including three ranch hands in Texas desperately trying to move cattle away from the flames.

Here are some images from the ground.

While area politicians like Inhofe are scrambling to bring relief to the areas devastated by the conflagration, they are eerily silent on its context: climate change. No single event like a wildfire can be directly tied to a long-term trend like climate change, but science suggests that wildfires will be more common in the Southern Plains region as temperatures rise.

As this 2015 report from the USDA Southern Plains Climate Hub puts it, “Highly variable weather has been a benchmark of life and agriculture in the Southern Great Plains since long before the states of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas were formed.” However, “over the last 15 years, the region has experienced an increasing frequency of some of the more extreme events central to agriculture, a direct result of more dynamic atmospheric behavior,” including “extensive, crippling periods of drought that ended with record-breaking downpours and flooding.”

And more droughts mean “more frequent fires,” the report adds. One major driver is rapid transitions from wet weather to drought, Jean Steine, director of the USDA Agricultural Research Service’s Grazinglands Research Laboratory in El Reno, Oklahoma, told me. “We had pretty nice rainfall last summer,” she said. And that triggered lots of growth in grass and other plant matter. Come fall, the rains abruptly stopped—drying out all that grass. In late winter, “really strong winds and low humidity set in”—creating perfect conditions for big fires, Steine said, adding that this year’s are the biggest on record for the region.

The conditions are eerily similar to those that enabled the catastrophic fires that swept through the region in 2010-’11— a “particularly wet” summer and spring “led to an abundance of shrub and grass growth,” which them dried out on a subsequent drought, “making the ideal fuel for rapid wildfire development and growth,” as this National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report notes.

And sudden swings are increasingly common in the region, a peer-reviewed 2015 paper from University of Oklahoma meteorologists shows. They looked at the frequency of what they call “dipole events” (a drought year followed by a year of unusually high rains). They found that between 1896 and 1954, only three dipoles occurred in the Southern Great Plains region; while between 1955 and 2013, seven such events occurred.

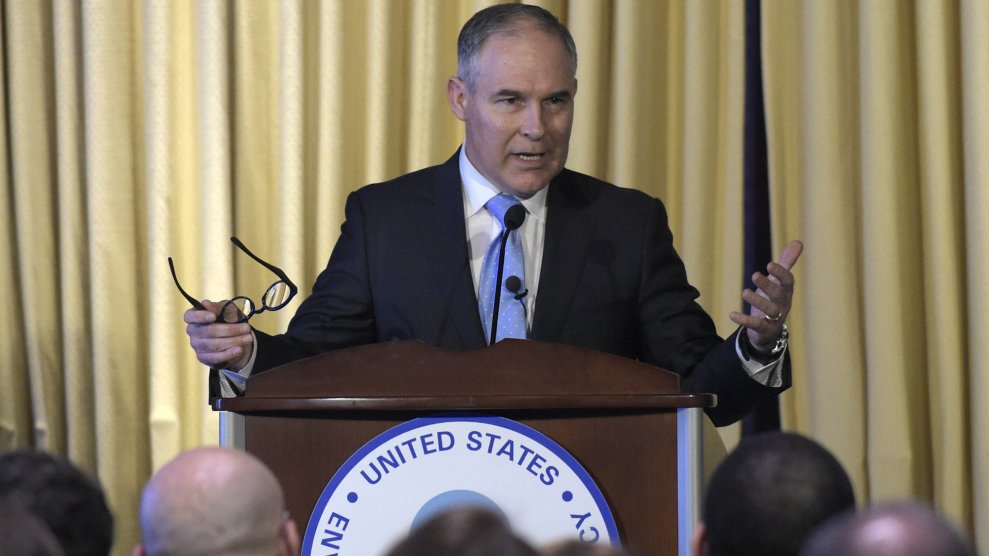

Meanwhile, the three states affected by this year’s fires are all dominated by politicians who downplay human contribution to climate change and battle efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Oklahoma’s Sen. Inhofe is one of Washington’s most tireless climate deniers. Former attorney general Scott Pruitt, now serving as the director of the US Environmental Protection Agency, is tightly allied with the fossil fuel industry and recently argued that carbon emissions don’t drive climate change. Oklahoma’s governor, Mary Fallin, underlined her blasé attitude toward climate change with a recent executive proclamation declaring an “oilfield prayer day,” wherein “people of all faiths are invited to thank God for the blessings provided by the oil and natural gas industry.”

Kansas Governor Sam Brownback used to acknowledge the need to address climate change; but later bitterly fought President Barack Obama’s plan to limit carbon pollution from existing power plants, deeming it “more of the Obama administration’s war against middle America.” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott is a devout climate denier, as is his predecessor, Rick Perry, now chief of the US Department of Energy.