Pat Sullivan/AP Photo

Just weeks after Arkansas attempted to execute eight men in 11 days, lethal injection in back in the news. On Tuesday, Georgia is scheduled to execute J.W. Ledford for a 1992 murder. Texas was slated to put Tilon Carter to death on Tuesday as well, but he received a stay last week after the state’s court of criminal appeals decided to hear his claims that the jury was misled.

Georgia will use a controversial one-drug protocol—a heavy dose of pentobarbital, an anesthetic that critics say can fail to render inmates fully unconscious. On Monday, Ledford requested that Georgia execute him by firing squad, instead. He argues that a pain medication he takes has altered his brain chemistry so much that the pentobarbital may not work properly, leading to excruciating pain. (Texas was planning to use pentobarbital to kill Carter, as well.)

Americans generally accept the claim that lethal injection is a humane and painless way to kill convicted murderers. A 2014 Gallup poll found that 65 percent of Americans believe that lethal injection is the “most humane” form of capital punishment. According to a 2015 YouGov poll, just 18 percent of respondents described lethal injection as “cruel and unusual punishment,” which is prohibited by the Eighth Amendment. But, despite its widespread use, there is virtually no scientific data to suggest that lethal injection is humane. There’s been very little research done on the effects of lethal injections on humans at all—but the science that is available suggest that inmates may actually experience immense pain before dying.

On a recent episode of our Inquiring Minds podcast, Kishore Hari interviews Teresa Zimmers, an associate professor of surgery at Indiana University School of Medicine. Zimmers, who has spent years researching lethal injection, is sharply critical to the ways in which states kill the condemned.

“What we have here is masquerade,” says Zimmers. “Something that pretends to be science and pretends to be medicine but isn’t.”

Prior to 1972, when the Supreme Court halted executions nationwide, states used a variety methods to put inmates to death, including gas chambers and the electric chair. After the court ruled in 1976 that the death penalty did not constitute cruel and unusual punishment, an Oklahoma state legislator called the state’s medical examiner, Jay Chapman, and asked him if he could come up with a new and humane way to execute prisoners. Chapman has said that he initially thought he wasn’t qualified for the task, but he nonetheless proposed using fatal doses of pharmaceuticals that are typically used to put patients.

Chapman came up with a three-drug protocol: Sodium thiopental, an anesthetic to put the inmate to sleep; pancuronium bromide, which causes paralysis; and potassium chloride to stop the heart. Other states soon adopted this protocol, but there was never much scientific evidence showing it was truly humane.

“It’s not at all clear that the protocol works as advertised,” explains Zimmers.

In 2007, Zimmers was part of a team that analyzed execution records from California and North Carolina and found that lethal injection might actually lead to painful chemical asphyxiation. Zimmers’ team suggested that the thiopental dosages being used might not be high enough to induce sleep and that potassium chloride might not reliably stop the heart. The potential result: a paralyzed inmate who remains aware while dying from the inability to breathe. Zimmers’ paper concluded:

[O]ur findings suggest that current lethal injection protocols may not reliably effect death through the mechanisms intended, indicating a failure of design and implementation. If thiopental and potassium chloride fail to cause anesthesia and cardiac arrest, potentially aware inmates could die through pancuronium-induced asphyxiation. Thus the conventional view of lethal injection leading to an invariably peaceful and painless death is questionable.

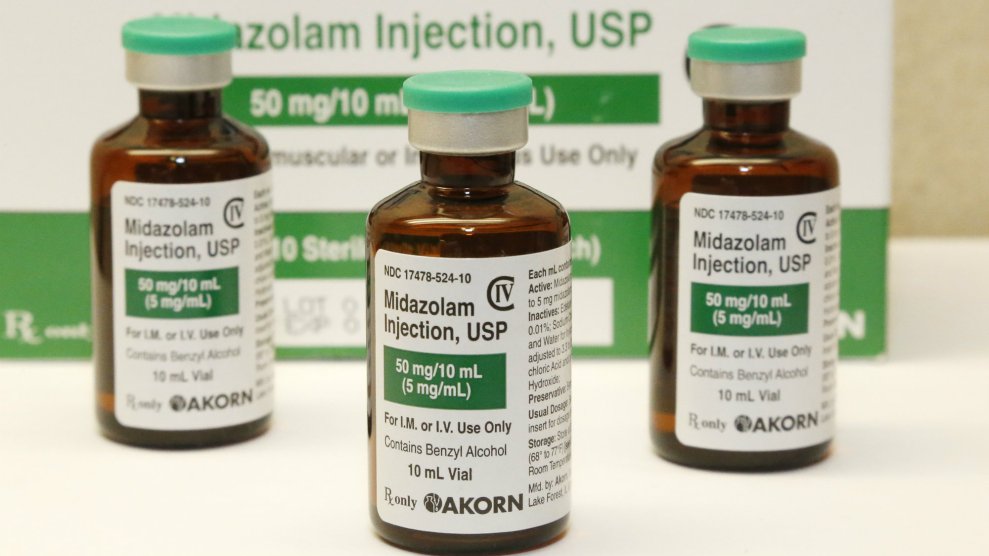

Beginning around 2009, European pharmaceutical companies began refusing to sell their drugs to American states that intended to use them to put inmates to death. The shortages led to a rush to find different lethal injection methods, such as replacing the sodium thiopental with a drug called midazolam or using a single fatal dose of an anesthetic.

And just like with the original cocktail, these new lethal injection techniques have been developed with little scientific rigor. “There’s been a very active substitution of drugs into this protocol with, of course, no corresponding investigation,” says Zimmers.

When Oklahoma used the one-drug protocol of pentobarbital in the execution of Michael Wilson in January 2014, the inmate’s last words were, “I feel my whole body burning.” A few months later, the state tried to put Clayton Lockett to death using a three-drug protocol that included the anesthetic midazolam. Lockett mumbled and writhed on the gurney, before dying of a massive heart attack about 40 minutes after the procedure began. Oklahoma’s executions are now on hold.

Despite the controversy surrounding midazolam, last month Arkansas rushed to execute eight men in 11 days when its supply of the drug was set to expire. After a series of legal setbacks for the state, only four were put to death. The last man to die, Kenneth Williams, reportedly convulsed, jerked, lurched, and coughed for 10 to 20 seconds after prison officials administered midazolam.

Often, the debate over capital punishment centers around the morality of government-sponsored killing or the potential for an innocent person to be executed. But Zimmers suspects that for many people, support for the death penalty relies on the notion that states are using compassionate, scientifically validated method to kill inmates. That notion, Zimmers argues, is simply wrong.

“They should understand that this isn’t science,” she says. “This is a pretense of science.”

Inquiring Minds is a podcast hosted by neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas and Kishore Hari, the director of the Bay Area Science Festival. To catch future shows right when they are released, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes or RSS. You can follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook.