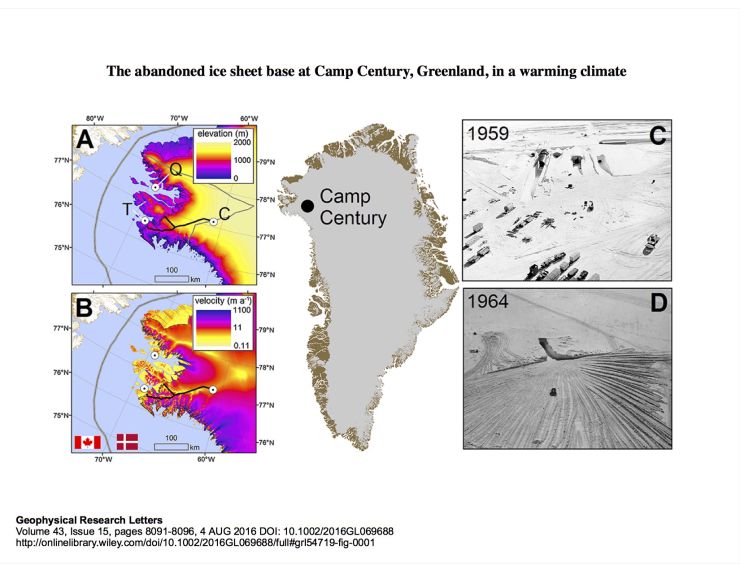

A logistical cargo carrier drops off supplies at Camp Century in Greenland in 1959. Keystone Press Agency via ZUMA

This story was originally published by Fusion and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Over the last century, many glaciers have pulled back farther than humans have ever previously witnessed. While the retreat of glaciers, and changes in the cryosphere more generally (which includes ice sheets and permafrost), can be seen as purely symbolic representations of the unwavering march of climate change, they are shifting geography as they melt and thaw, leaving dangerous implications behind.

Camp Century is only one such instance. Built underneath the surface of the Greenland Ice Sheet in 1959 by the the US Army Corps of Engineers as part of Project Iceworm, the project was designed to create a network of mobile nuclear missile launch sites in Greenland. Intended to study the deployment and potential launch of ballistic missiles within the ice sheet, the base was eventually abandoned and decommissioned in 1967.

“Before it shut down it was almost an entire underground city, with bars, theaters and other buildings,” says Garry Clarke, a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of British Columbia. Clarke conducted graduate work at the site in 1965, before it was decommissioned. “Before I got there, the whole thing was powered by nuclear energy. Since the idea of shielding the missiles from detection wasn’t working very well, some took to calling Camp Century the ‘Atomic City.’”

While the base’s nuclear generator was removed as part of the decommissioning, various kinds of waste remain at the base, including sewage, persistent organic pollutants, diesel fuel, and the radiological waste from the removed nuclear generator. At the time, it was expected all of this would be safely buried in the ice sheet, never to see the light of day.

A 2016 study found that climate change has altered the situation though. According to it, the rate of ice melt on the ice sheet could outpace the expected gains made from snowfall, releasing the the waste in the years after the 2090s. Addressing the released waste would be an expensive proposition for the US and Denmark, which originally gave the US permission to establish the base.

William Colgan, a glaciologist at York University in Toronto, Canada, and lead author of the study believes that a first step towards addressing this would be to conduct additional research on the ice sheet and what it contains, and he’s currently in the process of returning to the ice sheet. As the study notes:

Climate change is likely to amplify political disputes associated with abandoned wastes in a variety of settings. In this context, the shifting fate of abandoned ice sheet military bases under climate change may provide a microcosm through which to examine the multinational and multigenerational challenges presented by climate change.

As the ice sheets of Greenland continue to slowly melt, other unforeseen results of changes to the cryosphere have more immediate consequences.

Earlier this year, melting on the Kaskawulsh glacier changed the distribution of water, and route, of two rivers in Canada. The Slims River, which originally emptied out into the Bering Sea, now empties out into the Bay of Alaska, thousands of miles from its original outlet, and the volume of water in it decreased sharply. Meanwhile the lake it fed, Kluane Lake, has seen its water level drop as well. In the opposite direction, the Alsek River, which flows through protected areas and is a popular white water rafting destination, has seen a massive surge of water. While the Slims and Alsek were originally similar sizes, the Alsek is now 60 to 70 times larger than the Slims, according to a 2017 study.

“Over the last 100 years as the glacier has been receding, exacerbated by climate change, it has become less of an obstacle for water flowing in one direction or another,” says Dan Shugar, Assistant Professor of Geoscience at the University of Washington Tacoma and the lead author of the study on the event. “Last summer was the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

This is the first observed case ever of “river piracy,” or the diversion of the headwaters of one stream into another. While the areas the rivers flow through didn’t contain large population densities, it still has an impact of nearby communities.

Two first nation villages reside on the shores of Lake Kluane and depend on its fish as a substantive part of their traditional diet. Because of the changes in the lake’s water level, as well as the sediment within it “they’ve already noticed changes to where they can access their fishing grounds,” says Shugar:

And just recently a Yukon Member of the Legislative Assembly raised the issue of Kluane lake levels. Because they’ve dropped so much, boat access to the lake is becoming imperiled. There are only two main boat accesses to the lake and one of them is no longer a feasible launching spot. So you are reducing the capacity for search and rescue if you can’t access the lake quickly and someone is out there and in trouble. These are real impacts.

Humans have an investment in keeping things similar to how they are, because that allows for predictability. These sorts of geographical shifts have impacts beyond their immediate consequences. Glaciers and the rivers they distribute feed numerous reservoirs, contributing to water management and crop growth.

“We dam rivers to make hydroelectric power, control floods, and hold summer glacial flows to sustain agriculture,” says Clarke. The size and sources of these reservoirs is an important factor in buffering for the unpredictable. “If you haven’t got much in the bank you can’t stand long periods without water,” he says. This is an issue not just on the level of a farmer who might access distributed water, but for the economy more generally. Things such as the collection and distribution of food and agriculture are centralized around assumptions that the grains will be grown at a certain location, at a certain time. River piracy can disrupt those assumptions, and the economic stability that goes with it.

Shugar’s next project illustrates perhaps an even more destructive example of the impact of retreating glaciers. As glaciers in valleys retreat, the valley walls are often incredibly steep because they’ve been carved out by the previous push of the glacier.

“They’re much steeper than if there had just been a river there. So when it melts away, the valley walls are less supported because there is no glacier there, and they sometimes collapse catastrophically,” says Shugar. This results in a gigantic landslide, the likes of which occurred in Alaska last July when a miles-long landslide next to the Lamplugh Glacier, in Glacier Bay National Park, resulted in seismic tremors that registered at 5.5, according to the New York Times.

“These landslides might come down and block a river for example, which could then burst out causing a big flood, or where they might come down into a lake or a fjord, essentially causing a gigantic tsunami,” says Shugar.

According to the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute, just such an event happened in October of 2015, when a mountainside near Tyndall Glacier fell into Icy Bay in Alaska, resulting in a tsunami. The wave that reached trees that were more than 500 feet up on a hillside adjacent to the bay.

This melting will only continue. According to a recent study from the US Geological Survey and Portland State University, Montana’s Glacier National Park’s glaciers have shrunk by an average of about 39 percent since 1966, with some shrinking by as much as 82 percent.

Currently about 10 percent of the land on Earth is covered with glacial ice—including glaciers, ice caps, and the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica—stretching over 5.8 million square miles and storing about 75 percent of the world’s fresh water. Were melting of land ice to continue until it was all gone, sea level would rise some 230 feet, drowning the coastal cities of the world. And as the cryosphere continues to warm and change, it will only exponentially increase the pace of climate change, by releasing more CO2 and methane in the atmosphere, decreasing the reflective surfaces on the Earth, and increasing the surface area of the ocean.

“The glaciers are telling us something,” says Clarke. “We need to listen if we care about our future.”