Evan Vucci/AP

This story was originally published by HuffPost and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Chris Christie’s defining moment on climate change came early in his first term as New Jersey’s governor.

On May 26, 2011, the brash, trash-talking Republican acknowledged for the first time that humans were causing the climate to change. Then, just three minutes into his 14-minute speech, he announced the Garden State’s withdrawal from a popular and effective interstate pact to lower planet-warming emissions and raise money for energy efficiency projects.

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI, includes Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont, which have put limits on carbon dioxide emissions from power plants and created a cap-and-trade market that allows utility companies to buy and sell permits to pollute. The program is credited with reducing average utility bills by 3.4 percent across the Northeast, driving $2.7 billion in revenues reinvested into public projects and creating at least 30,200 new jobs over the past eight years.

Yet Christie called it a “failure.” He insisted that the burden RGGI put on companies would drive job creators over the state line to Pennsylvania, New Jersey’s fossil fuel-rich neighbor and one of the few states in the region outside the group.

“RGGI does nothing more than tax electricity, tax our citizens, tax our businesses with no discernible or measurable impact upon our environment,” Christie said in the speech speciously titled “New Jersey’s Future Is Green.”

“It doesn’t make any sense, environmentally or economically,” he added.

Months later, he vetoed a bill passed by the Democratic majority in the state legislature to rejoin RGGI. The next year, he rejected similar legislation. Last month, he struck down yet another bill, declaring, “The third time will not be the charm.”

“It was … the most significant policy decision,” Matt Katz, author of the 2016 biography American Governor: Chris Christie’s Bridge to Redemption, told HuffPost. “His pro-environment promises to move toward solar and wind energy sources could’ve been a part of his legacy, but they turned out to be mostly empty efforts.”

It’s a legacy that strikingly mirrors that of President Donald Trump, who made eliminating environmental regulations a top priority, aggressively courted fossil fuel interests, and withdrew the United States from the Paris climate accord just five months after taking office. The White House’s decision to drop out of the agreement to lower carbon emissions, signed by every country except Syria and Nicaragua, drew similar condemnation, particularly for seeming to lack logic beyond shoring up support from his base in anticipation of the next election.

Christie’s positioning on climate change has been a break from his predecessors in New Jersey, nearly all of whom have made conservation a key concern. Gov. Brendan Byrne (D) preserved the Pine Barrens in the 1970s. Gov. Tom Kean (R) increased protections for wetlands with a 1984 executive order and started a climate change task force. Gov. James Florio (D) set aside the Highlands, a geological formation running along the Delaware River, in the early 1990s. Gov. Christine Todd Whitman (R) drastically improved ozone levels, reduced beach closings to a record low and later went on to lead the Environmental Protection Agency under President George W. Bush. Gov. James McGreevey (D) expanded wetlands protections by nearly 400,000 acres in 2004. Under Gov. Richard Codey (D), New Jersey became a founding member of RGGI in 2005. Two years later, Gov. Jon Corzine (D) beefed up “stream encroachment” rules to keep development away from areas at high risk of flooding.

“Christie’s legacy will be trying to roll back every other governor’s environmental legacy,” Jeff Tittel, director of the Sierra Club’s New Jersey chapter, told HuffPost. “He’s been the most anti-environmental governor this state has ever seen.”

A spokesman for Christie declined to comment, but referred HuffPost to the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. The agency in turn referred HuffPost to Christie’s May 2011 speech.

“At the end of the day, RGGI allowance costs are passed along to New Jersey ratepayers,” Larry Hajna, a spokesman for the agency, wrote in a follow-up email to HuffPost. “We also estimate for every dollar we invest in RGGI, our ratepayers would only get about 50 cents in return.”

Most politics watchers in New Jersey think it’s no coincidence that Christie pulled out of RGGI three months after meeting with fossil fuel tycoon David Koch in New York, one month before headlining the Koch brothers’ conference in Colorado and nearly a year ahead of the 2012 election. His initial meeting took place in secret, and the press was never notified that he was out of state. Audio obtained by Mother Jones revealed that Koch praised Christie for pulling out of RGGI.

“Already at this point Christie was plotting a future presidential run, and to do so in the Republican field at that moment in history he needed a conservative environmental win,” Katz said. “He threaded that needle, preserving his chances for re-election in a blue state by claiming his pullout wasn’t about climate change.”

But Christie’s unwavering opposition to RGGI proved so unpopular, not even his own deputy can defend it. Lt. Gov. Kim Guadagno, now running as the Republican nominee for governor, pledged to reinstate New Jersey as RGGI’s 10th member.

Ricky Diaz, her spokesman, declined an interview request on Monday after four emails and three phone calls.

But Guadagno, 58, maintained her support for RGGI even under blistering criticism from a Republican primary opponent who pilloried the program as a “job-killing cap and trade energy tax.”

“If we are going to nominate a Republican who embraces cap and trade, and the excessive taxes and regulations it brings with it, what does our party stand for anyway?” Jack Ciattarelli, a Republican legislator who came in second for the nomination, said in May. “We need contrasts with Phil Murphy this fall, not a rubber stamp for bad policy ideas.”

A spokesman for Murphy said the former Goldman Sachs banker who won the Democratic nomination in June would make rejoining RGGI “one of the first acts in office.” But he said he was still determining whether to do so through executive action or by signing legislation.

“Whatever avenue is the one that is the most binding way is the way we would do it,” Derek Roseman, the spokesman, told HuffPost.

He assailed Guadagno’s record of supporting Christie’s agenda, asserting she had an “extreme lack of credibility on this issue.”

“She sat there when Christie pulled us out of RGGI, and for seven-plus years, never said anything or called the governor out for his error,” Roseman said. “That for us is not an act of omission, but an act of commission.”

Diaz did not respond to questions about how Guadagno would renew New Jersey’s status in RGGI, but hit back with criticism of Murphy’s history as an investment banker.

“Phil Murphy spent years profiting off oil and gas companies when he worked at Goldman Sachs, so he doesn’t have much credibility on these topics and his attacks ring hollow,” he wrote in an email. “Kim Guadagno is a strong believer that we must protect our environment and lead on things like renewable energy.”

He declined to comment on whether she planned to sign legislation or reinstate RGGI through executive action.

Murphy appears to be on track to deliver what The Atlantic called in June “a decisive victory” on Nov. 7. He led Guadagno 50 to 25 percent in a Quinnipiac poll from May.

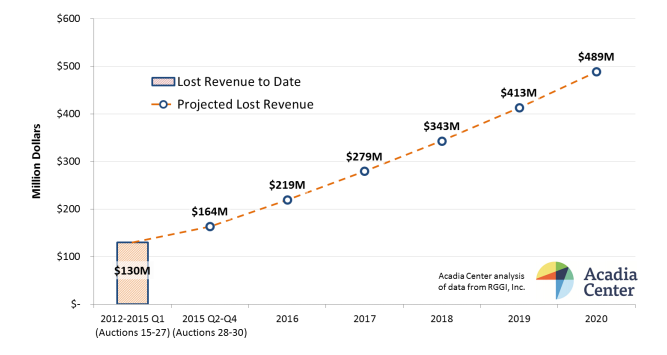

Contrary to what Christie said in 2011, New Jersey has lost money as a result of exiting RGGI. The state lost out on $130 million in proceeds from auctions where RGGI sells emissions permits and could miss out on another $359 million by the end of 2020 if it doesn’t rejoin, according to estimates by the Acadia Center think tank. If the sum of that money were invested in energy efficiency programs, as RGGI is designed to facilitate, New Jersey would save 15.3 million megawatt hours of electricity, more than all the power produced by the state’s coal-fired plants from 2010 to 2012.

The state’s re-entry to RGGI would come at a critical point for the program. Last year, RGGI embarked on a full review to determine whether to adopt a lower cap and stricter standards. The results of that review could come in the next few weeks. Sources familiar with the negotiations told HuffPost last month that it was “imminent” and said the talks had accelerated following Trump’s drastic rollback of climate policies.

This chart, from a 2015 Acadia Center report, shows how much money New Jersey stands to lose out on by closing itself off from RGGI auction proceeds.

Acadia Center

The nine remaining states are deciding between three different options to ramp up the rate at which RGGI reduces emissions. But the states are split between those who want the most ambitious target, such as New York and Massachusetts, and those that want the more modest choice, including Maine and New Hampshire. The difference in cost between the most and least ambitious targets comes out to less than one-tenth of one penny more per kilowatt hour of electricity over the current standard, yet the impact would be huge. Choosing the most aggressive reduction rate would avoid 99 million short tons of carbon dioxide emissions, according to the Acadia Center.

It’s unclear how the results of that decision would affect New Jersey. But, absent the goal of courting contributions from climate change-denying billionaires, the case for returning to RGGI becomes much stronger, said Jackson Morris, the Natural Resources Defense Council’s eastern energy director.

“It didn’t make sense before other than that it was appeasing to the Koch brothers,” Morris told HuffPost last month. “It’s part and parcel of what we’ve seen, which was a hyperpartisan approach to not only the environment, but many issues.”