White stork© Imago/ZUMA

This story was originally published by CityLab and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Zozu, like any other white stork in Europe, typically flies to southern Africa for the winter. Yet when researchers at Germany’s Max Plank Institute for Ornithology tracked the bird’s path using a GPS logger in 2016, they found that he and a few others had skipped the grueling migration across the Sahara Desert. That year, the birds stopped, instead, in cities like Madrid, Spain, and Rabat, Morocco. Apparently, they had developed a taste for junk food, in particular the stuff that piles up in landfills along the migration route.

When it comes to how human activity has altered animal behavior, this is one of the more glaring examples featured by geographer James Cheshire and visual designer Oliver Uberti in their latest book, Where the Animals Go. In it, they mined the data of nearly 40 studies that used sophisticated technology to track how and where animals migrate, turning raw numbers into a series of stunning maps.

Humans have long tracked the movements of animals by following their paw prints or staking out their natural habitats. That kind of observation still has its value today, but now biologists also benefit from a slew of satellite, radio, and GPS technologies that can track the digital footprints of, say, a herd of elephants or a flock of storks as they move across the globe. And at a time when both climate change and urban development are changing—and disrupting—the migration routes, there’s a new urgency in these kinds of research.

The tale of Zozu comes from a study in which researchers tracked the path of 70 juvenile storks from eight European countries. While the ones from Greece, Poland, and Russia followed the traditional path to the lush wetlands of South Africa, their counterparts from Germany, Spain, and Tunisia shortened their routes and settled for the dumpsters of Morocco, in northern Africa.

Uberti and Cheshire’s map contrasts, in particular, the path of Zozu and another stork who makes the traditional migration. “The first bird, 5P311, is flying all over the place and expending a lot of energy to forage in the wetland,” Uberti says, “whereas Zozu is plopped down on one spot binging on the landfill.”

But the key is to look beyond the zig-zagging line, and at the topographical change between Europe and Africa. “You can see how they have to cross this great expanse of desert in Sahara to get down to lusher feeding areas in South Africa,” Uberti adds. “Because so many storks die in that migration, you can kind of understand why some might [prefer] fast food in a landfill instead of making such a perilous journey.”

Zozu’s story may be unique, but it’s not uncommon as the human population becomes increasingly urban. The popular statistic is that today, over half of the world’s people live in cities—and animals are getting mixed in as well. Rapid urban development means more barriers for animals, and more integration between wildlife and humans.

“Cities have become their homes,” Cheshire says, pointing to the more optimistic cases of fruit bats binging on fruit trees within and outside the border of Accra, Ghana, and fishers thriving in upstate New York by navigating through culverts across town.

But there’s no doubt that cities have also become barriers. Last year, researchers at the Nature Conservancy looked at the effect of manmade barriers like roads, farmland, and urban infrastructure. They found that in the U.S., only 41 percent of natural lands were connected enough for animals to move through.

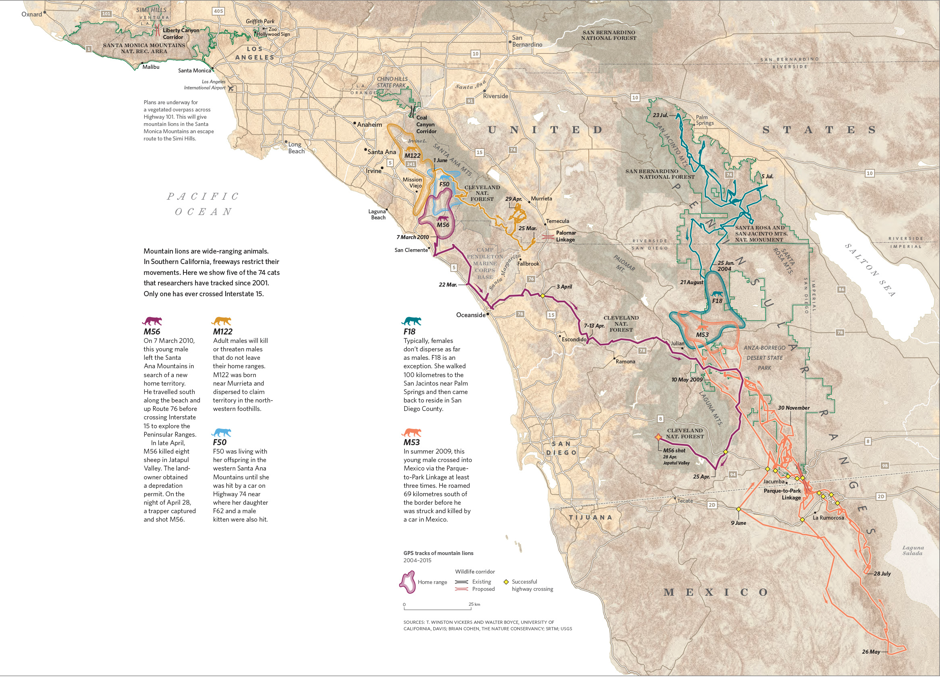

In southern California, mountain lions are in decline in part because of the expansive freeways that crisscross the state. When researchers tagged a sample of lions in Santa Ana with GPS devices, they found their natural habitats divided by as many as eight lanes of traffic, as well as houses, golf courses, and other private developments.

Despite proposals to build animal crossings after the fact, over- and underpasses have proven ineffective; they’re rarely used by the big cats. The risks go farther than just ending up as roadkill. The roads themselves become cages for mountain lion populations, isolating various groups and resulting in higher rates of inbreeding. This threatens their growth and survival as a whole.

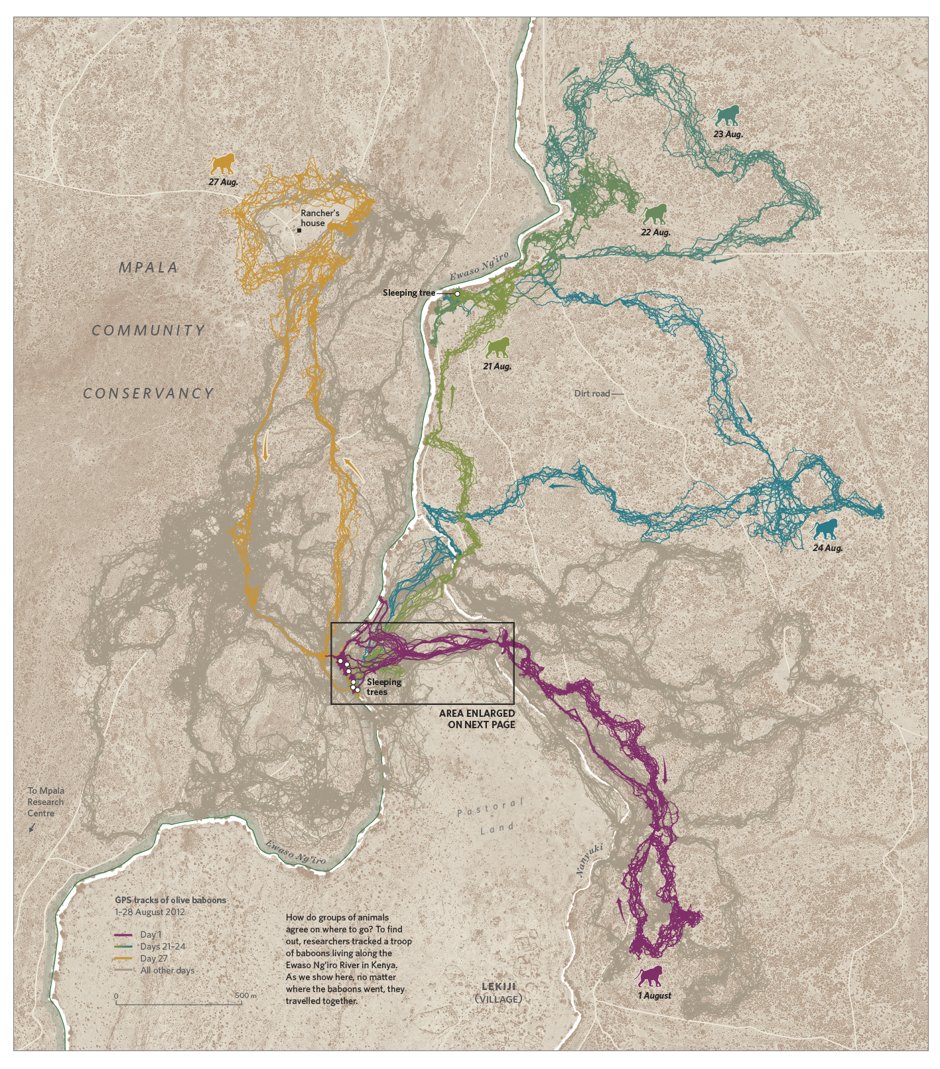

“In many ways, the damage is already done,” says Uberti. “What you see in Kenya is the counterpoint to that. The human development is nowhere near at the scale of the U.S., but it’s going to be in the coming century.” Before that happens, organizations like Save the Elephants have gone ahead and used GPS collars to track the migration patterns of the surrounding wildlife, collecting the data needed to eventually lobby the government against certain development projects and hunting programs, and for the creation of wildlife reserves and animal crossings.

The book highlights the fact that there is a large body of research surrounding animal migration—and for good reason. But what about human migration? For Cheshire, the book project slightly deviates from his day job as a human geographer. He says the two subjects have a lot in common, though. “Ultimately we’re interested in better understanding where the animals go,” he tells CityLab. “That insight can be applied to understand how we navigate through different cities.”

For example, studying how baboons move as a group can inform us about the crowd behavior of, say, human commuters. And the way researchers tracked landfills as population destinations for migrating storks isn’t too different from how one of his students use geotagged tweets to study the vibrancy of town centers in London. She mined million of tweets from shoppers—just as the stork researchers mined millions of location points—to map where they are traveling from.

What matters most is the quality of the data. “Theres a big difference between data and information,” he says. “We hear a lot about big data in the urban settings, and there’s all this excitement and hype around it. But for it to become information, you have to be able to extract from it important patterns and trends.”

And core of it all, Cheshire writes in the book, “Location is everything.”